New king, new expectations: What does Britain want from its monarchs?

Loading...

| London

Outside Buckingham Palace, thousands of tourists are in a jubilant mood. The springtime sun has burst out. So have the daffodils in nearby St. James’s Park. The only people not smiling are the famously stoic Buckingham Palace guards. Outside the gates, Generation Z sightseer Jasleen Kaur cheerfully banters with relatives who are visiting from India. But she’s hardly in awe of London’s most majestic home, which will host celebrations for King Charles’ coronation on May 6.

To her, the building looks “pretty much useless at the moment,” given that it appears to be uninhabited. Her thoughts on the monarchy strike a similar chord.

“It doesn’t really affect our day-to-day lives,” says the student from Nottingham. “To be honest, even the coronation and everything, we [aren’t] that interested in it.”

Why We Wrote This

The May 6 crowning of King Charles promises to swathe Britain in pomp and circumstance. But what does the monarchy represent to Britons today?

The crowds of tourists here, including visitors from all over Britain, are testament to the royal family’s legacy and heritage. But a March poll by international online group YouGov suggests that 52% of Britons are, like Ms. Kaur, not interested in the coronation. And long-term polling reveals a decline in support for the scandal-plagued institution in recent years. That’s particularly true among millennials and Gen Z.

Until now, the monarchy has endured because it has historically been stronger than the individuals within it. But some observers say that the widely loved Queen Elizabeth II, who reigned for seven decades, became bigger than the monarchy itself. By contrast, Britons aren’t as enthusiastic about her eldest son and heir. The new king’s challenge is to persuade modern-day Britain that the throne is still relevant. For Charles III, the coronation won’t just be a formal ceremony. It will be a vital opportunity to establish the tone of his reign and make a case for the monarchy.

“Charles is going to have to keep on working at it – and indeed, his son, obviously, too – if it’s going to continue to be valued as an institution,” says Sir John Curtice, senior research fellow at the National Centre for Social Research, in a phone interview. The center has been tracking trends in attitudes toward the monarchy since 1983.

The king is an “intriguing combination of avant-garde and deep tradition,” says royal historian Sally Bedell Smith, author of “Prince Charles: The Passions and Paradoxes of an Improbable Life.”

“The artist who was commissioned to do this first official portrait of him as king wanted very specifically to bring out his sympathy and humanity, which has always been there for people who have encountered him or who have known him through his charities,” says the author, who has just released “George VI and Elizabeth: The Marriage That Saved the Monarchy.”

But King Charles, who years ago spent several days living with a farming family in the Outer Hebrides, a chain of islands off the coast of Scotland, needs to convince citizens that he’s the people’s king.

“I believe in trying to create the fairest society possible, and I don’t think that can come about while there is somebody who, by birthright, is historically ‘better’ than everybody else and who rides around in a literal gold carriage,” says Andre Sterling, walking with his sister, Natalie, on Carnaby Street in central London. Behind them, a glittering crown hangs as a decoration over the pedestrian street. The siblings, whose parents immigrated to Britain from Jamaica, favor a republican form of government.

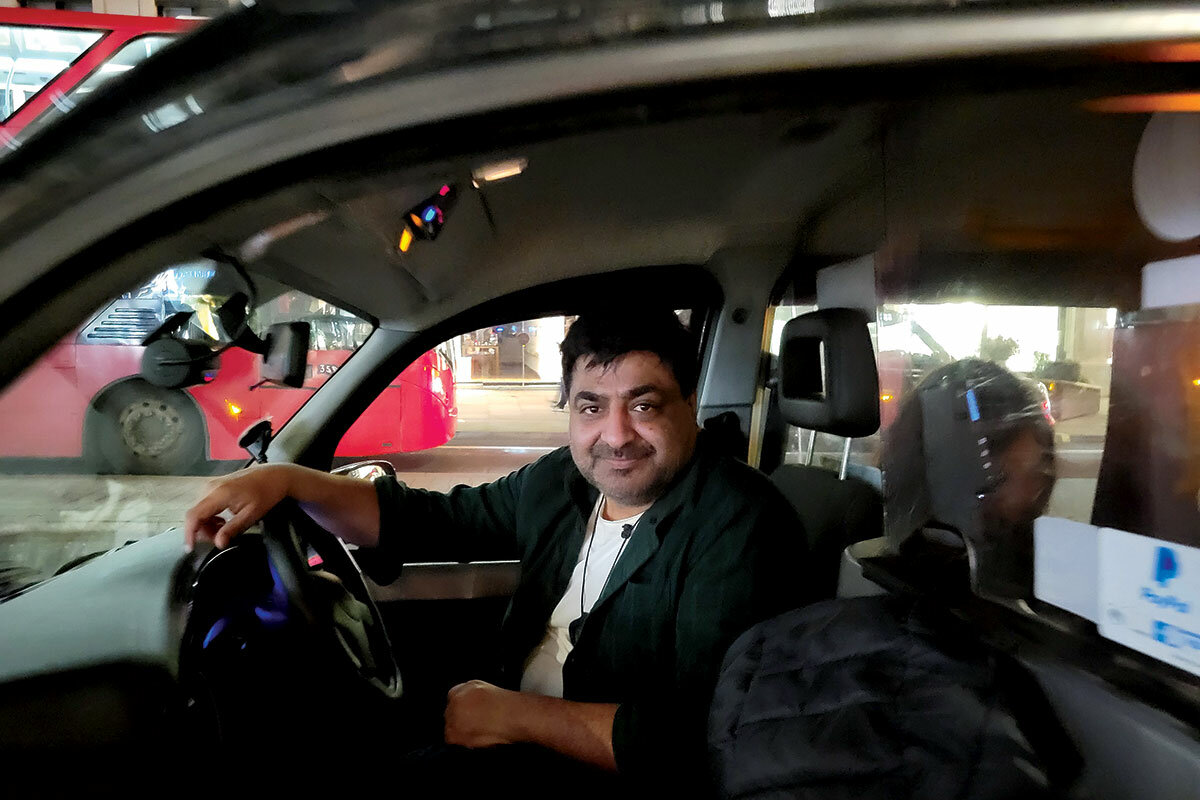

Over the past year, the treasury in Britain granted the royal family £86 million of taxpayer money. But cab driver Mohsin Raza, who loved Queen Elizabeth II, shrugs.

“I think in return what they bring to this country is massive, the goodwill and tourism,” says Mr. Raza, while waiting for his next customer on Regent Street.

At a time of rising inflation in Britain, the king’s coronation will be significantly smaller than the previous one: Some 2,000 guests compared to the more than 8,000 attendees for Elizabeth II’s ceremony. The king has made several other bids to seem attuned to modern Britain. In April, the palace announced his support for research into the monarchy’s historic ties to trans-Atlantic slavery. The palace also touted the values of inclusivity and diversity at the coronation. The concert the day after the ceremony will include a choir with amateur singers representing the National Health Service, LGBTQ+ community, and refugees.

The decision to include refugees in the choir may not have been intended as a critique of the Conservative government’s policy on deportation. But it did have a political impact. In Parliament, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was asked whether those singing in the choir risked being deported. It’s not the first time that King Charles has created a political stir. The British government asked the new king not to attend COP27, the United Nations climate conference, in Egypt last year. The king, renowned for his longtime advocacy for action on climate change, instead hosted a reception at Buckingham Palace for key COP27 figures prior to the conference.

“It would be difficult for him to unite people,” observes Kathy Clark, commuting on a train from London to a small town in Surrey. “He’s already expressed a wide range of views about things that the people will have opinions on.”

Though Ms. Clark says Charles has been vindicated in his longtime advocacy for the environment, she prefers the queen’s policy of not taking public stances.

In his inaugural speech on national television following the passing of Queen Elizabeth, the king stressed that he’d respect the apolitical role of the crown. The monarchy can, however, exert soft power.

“It can give attention to parts of civil society which aren’t of interest to politicians,” says Bob Morris, co-editor of “The Role of Monarchy in Democracy” and an honorary staff member of the constitution unit at University College London. The current Princess of Wales, Kate, “is interested in, for example, early childhood development. If you took an ultra view, you could say, ‘Well, this is interfering in politics,’ but it’s not. It’s trying to give attention to issues which she feels strongly about.”

Queen Elizabeth made the symbolic, yet political, gesture of shaking the hand of former IRA commander Martin McGuinness in 2011. At the time, Mr. McGuinness described it as an opportunity for “a new relationship between Britain and Ireland and between the Irish people themselves.”

King Charles may have a similar task – to create a sense of common cultural heritage to bind Britain together at a time when some in Scotland and Wales favor independence.

“He’s seen as a product of England for many in the Celtic fringes,” says royal watcher Tessa Dunlop, author of the new book “Elizabeth and Philip: A Story of Young Love, Marriage and Monarchy,” “So that is an issue for [the monarchy] as a uniting force within Britain, which is really key in terms of their role within the United Kingdom, because that’s one of our massive fault lines: Are we going to hold it together?”

Polls consistently show less support for Charles and the monarchy within Scotland. More recently, support throughout Britain has taken a dip. Contributing to that may be problems facing Prince Andrew, who last year settled a sexual assault case. In addition, there's the family rift with Prince Harry and his wife, Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, which the British media never tires of writing rancorous headlines about. Prince Harry will be attending his father's coronation.

Last year’s NatCen survey observed that “The 55% who said it was ‘very’ or ‘quite’ important for Britain to have a monarchy in 2021 is the lowest figure on record, while those who said it is either ‘not at all important’ or that it should be abolished reached a quarter (25%) for the first time.”

“The youngest generation of under 35 is particularly less likely to be enamored or think the monarchy is really important than, well, younger people 20 years ago,” says NatCen’s Sir John. If that persists it could lead to a generational shift.

Back outside Buckingham Palace, tourist Matt Raybold expresses confidence that the new king will be “fine,” because he has inherited the character of his parents. “We’re very pro-monarchy,” says the police officer from Birmingham, who’s sightseeing with his family. “It’s all we’ve ever known and we wouldn’t want anything else.”

Nearby, flatbed trucks equipped with whirring cranes are laying panels of flooring over the grass alongside the road where well-wishers will throng to the king and queen consort in their horse-drawn carriage en route to Westminster Abbey.

“One thing we like in this country is a bit of pomp and circumstance,” says Mr. Raybold. “It’ll just give everyone an excuse to forget a little bit about everything that’s going on. And just have a good time together as a family and as a country.”