France won’t apologize to Algeria for war. Enter the French people.

Loading...

| Paris

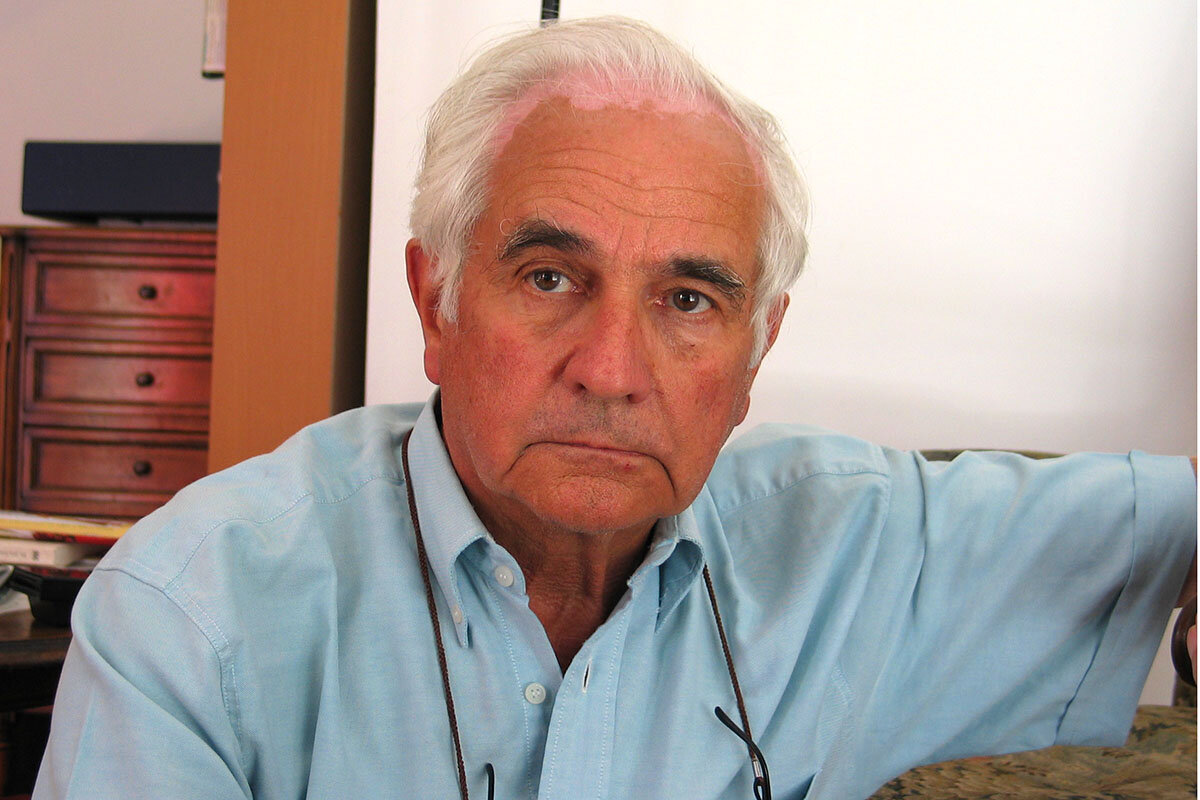

Stanislas Hutin never wanted to be a soldier. But when he was called up by the French army to fight in the Algerian War of Independence in 1955, he had no choice. For two years, Mr. Hutin witnessed death, torture, and violence as the French empire fought to hold power over what was, at the time, colonized territory. He kept a journal to cope with the horror.

“Colonization became a somber image of my country,” says Mr. Hutin, who is now 92 and lives in Paris. “When I arrived in Algeria, I saw flagrant injustices. I couldn’t tolerate it.”

In 2002, Mr. Hutin published his wartime journal to share his experiences of a battle he never believed in. But he wanted to mend things further. In 2014, he joined a local nonprofit that helped former French soldiers donate their military pensions to aid projects in Algeria.

Why We Wrote This

What happened in Algeria was in stark contrast to France’s founding principles of liberty, fraternity, and equality. That paradox, say historians, is at the heart of France’s struggles to come to terms with its colonial past.

Since then, he has been giving his annual €800 (about $844) stipend to 4ACG (Anciens Appelés en Algérie et leurs Amis Contre la Guerre), which goes toward education programs for youth and women in the former French colony. The group, which now counts about 400 members, has raised more than €1 million (about $1.06 million) since 2004.

“I didn’t even hesitate one second. It’s the judicious thing to do,” says Mr. Hutin. “We need to recognize the injustices and repair them.”

France, like many countries including Britain and the Netherlands, has struggled to come to terms with its colonial past. Unlike other European countries, such as Germany, which have agreed to some form of reparations, France has notably refused to apologize – as recently as 2021.

Some people, both Algerian and French, question whether an apology can undo decades of pain and suffering. Others ask, how can France move forward from its colonial past if it can’t even say it’s sorry?

In the meantime, individuals like Mr. Hutin and nonprofits like 4ACG are taking matters into their own hands – offering what recompense they can for what they see as a legacy of injustice.

Today, European colonization, and the harm it wrought, is increasingly questioned. France and what it owes to the Algerian people – monetarily or otherwise – show just how difficult it can be to offer amends amid its tendency to still romanticize its past as a global power.

“We need a new retelling of history that shows the complexity of what happened, is inclusive, and respects both sides of a common story,” says Christelle Taraud, a French historian who specializes in colonization and decolonization. “There’s no question that the place of Algeria, 130 years of colonialization, has an impact on our society today. Our ability to live together in peace means repairing this history.”

France has made some moves to acknowledge the harms it perpetrated in Algeria, whose relationship with Paris was the closest but the most fraught of any of the former colonies. As a presidential candidate in 2017, Emmanuel Macron went further than any French president, calling France’s colonization there “a crime against humanity.” This came after former President François Hollande acknowledged his country’s “unjust and brutal” occupation in 2012.

While the French government has offered some amends to some of its former colonial soldiers and returned stolen artwork as acts of reconciliation, it has struggled to repent or offer sweeping financial reparations to Algeria or other former French colonies.

Meanwhile, conservative voices have hijacked the reparations debate in what critics say is an effort to whitewash colonialism. At the same time, generations of Franco-Algerians are working to reconcile their place in French society, in the face of a continuing national dialogue about immigration and identity.

A colonial legacy

Though the French empire had been present in Africa since the 17th century, its global colonial influence truly began with the conquest of Algeria in 1830. Even as France went on to exert influence in West and Central Africa, its relationship with Algeria has always been unique. Algeria was the only French colony that was considered a part of France and divided into three provinces.

But Algerians living under French colonial rule held an inferior status and were referred to as indigènes, or natives. Most were prevented from going to school, and when Algeria gained independence in 1962, more than 85% of the population was illiterate. Before the Algerian War – which killed between 400,000 and 1.5 million Algerians – historians say one-third of the population had already been wiped out, due to epidemics and invasions.

“There was already a very high level of trauma within the Algerian population, even before the Algerian War,” says M’hamed Oualdi, a history professor of early modern and modern North Africa at Sciences Po-Paris.

What happened in Algeria was in stark contrast to France’s founding principles of liberty, fraternity, and equality. That paradox, say historians, is at the heart of France’s struggles to come to terms with its colonial past.

“Colonial violence creates a problem for France because it has always considered itself a model of democracy,” says Mr. Oualdi. “How can you be a democratic republic and, at the same time, a colonial power that was so violent?”

For decades, France has taken great pride in its conquests of countries across North and West Africa, espousing the glory of the empire in school textbooks while remaining silent on the inhumanities perpetrated. Just after the Évian Accords were signed in 1962, signaling the end of the Algerian War, France passed two decrees and three laws that prevented any pursuit of justice for crimes committed during the war.

The French government did not officially recognize the Algerian War until 1999. And historians continue to request that classified documents from the war be made public in order to see the full extent of crimes.

Other European countries have experienced the challenges of making reparations. In 2021, Germany, after six years of negotiations with the Namibian government, agreed to pay €1.1 billion for what is regarded as the first genocide of the 20th century, against the Herero and Nama peoples. The offer was rejected by the victims’ descendants, who said they were left out of the reparations process and sued the Namibian government this year.

In France, far-right groups have capitalized on these difficulties, glorifying what they consider colonialism’s success stories. After President Macron called colonization “a crime against humanity” during a visit to Algeria in 2017, Florian Philippot, vice president of the far-right National Front party, tweeted, “Mr. Macron, are roads, hospitals, French language, and French culture crimes against humanity?”

Similar debates have cropped up in other conservative bastions. Earlier this year, in the United States, Florida announced that the state’s new social studies curriculum would include lessons that claim slavery helped people “develop skills” that could be used for “personal benefit.”

Some say this is where French educators can provide balance. While there is a national history program, individual teachers have a certain level of freedom in how they teach. But France still lacks a significant body of work on colonialism written from the perspective of the colonized, versus the colonizer. The concept of postcolonial studies has only been present since the early 2000s in France, nearly three decades after its emergence in Anglophone universities.

“French education has always glorified colonialism,” says Benoît Falaize, a French historian and specialist on the history of schools and education. “France constructed hospitals, schools, etc. There is this image of ‘La Grande France.’ How do we put a stop to this colonial trauma from generation to generation? That’s the difficulty educators face.”

“A desire to forget”

As France continues to stall on reparations and repentance, some Franco-Algerians are carving their own path on what those concepts should look like. In 2020, 24-year-old Farah Khodja launched the nonprofit Récits d’Algérie as a way to compile stories of life in colonial Algeria. Like many of her generation, Ms. Khodja spent summers in her mother’s native Algeria without learning the complexities of life under French rule.

That was the experience of Ali, who was born in Algeria and came to live in France at age 25. He says that although his father fought with Algeria’s National Liberation Army, he never spoke about his experiences.

“People of my parents’ generation didn’t talk very much. There was, I think, a desire to forget,” says Ali, now a Paris resident, who is a French public servant and declined to give his last name because he is not authorized to talk to the press. “The suffering they experienced was very deep, and they just wanted to move on.”

Rym Tarfaya, who was born in France to Algerian parents, says her grandparents never expressed hatred or bitterness about Algeria’s colonial – or postcolonial – period.

“They always transmitted memories of that time with a state of serenity,” says Ms. Tarfaya, who spent much of her childhood in Algeria and now lives in Paris. “It wasn’t ‘the mean French’ versus ‘the natives.’ It wasn’t black and white.”

Still, France’s modus operandi after Algeria’s liberation has had consequences for French society today. Immediately after the war, nearly 1 million Algerians resettled in France, causing housing and employment challenges for the French state. New arrivals were placed in public housing in city suburbs, which still suffer poverty, tension, and a lack of resources today.

Harkis – Algerians who fought for the French side during the Algerian war – were one of the groups segregated into ghettos, far from the city center. The French government granted them and their families financial reparations in 2022, when it passed a law that offers an average of €8,800 each to tens of thousands of applicants. But larger battles over reparations still loom.

Relations between France and Algeria remain strained, partly due to France’s inability to officially apologize for not only the eight-year war that claimed 1.5 million Algerian lives, according to Algerian officials, but also the 130 years of colonial rule. In 2021, respected historian Benjamin Stora reiterated in a government-issued report that France did not need to do so.

Because the issue has become so polarized, “the government will have trouble convincing the French electorate to take money out of the state budget to pay reparations,” says French economist Thomas Piketty.

French and Algerian historians met for the first time in April as part of a “memories and truth commission” to discuss the two countries’ history more openly.

“France killed and tortured; it needs to recognize what it did. But I don’t know if the government is capable,” says Rémi Serres, one of the founders of the 4ACG organization and a former French soldier in the Algerian War. He and other members of his nonprofit regularly visit schools to talk about the perils of war and travel to their former battleground as part of aid projects.

“Now, when we go to Algeria, we’re not necessarily welcome everywhere. We mistreated them for 130 years,” he says. “But most people understand that we’re coming as friends.”

This story was produced as part of a special Monitor series exploring the reparations debate, in the United States and around the world. Explore more.