For Ukrainians, memory fuels the fight for sovereignty

Loading...

| Kharkiv, Ukraine

The visitors enter the building on Yaroslavksa Street through a scuffed metal door and climb two flights of stairs under the weight of unwanted memories. In a gray office with blank walls, they meet attorneys with the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, who sit at desks behind laptops, poised to listen. Here the men and women and children reveal their anguish and loss. The lawyers type notes as they talk, and with each recorded narrative, the larger story of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine gains another detail that history cannot erase.

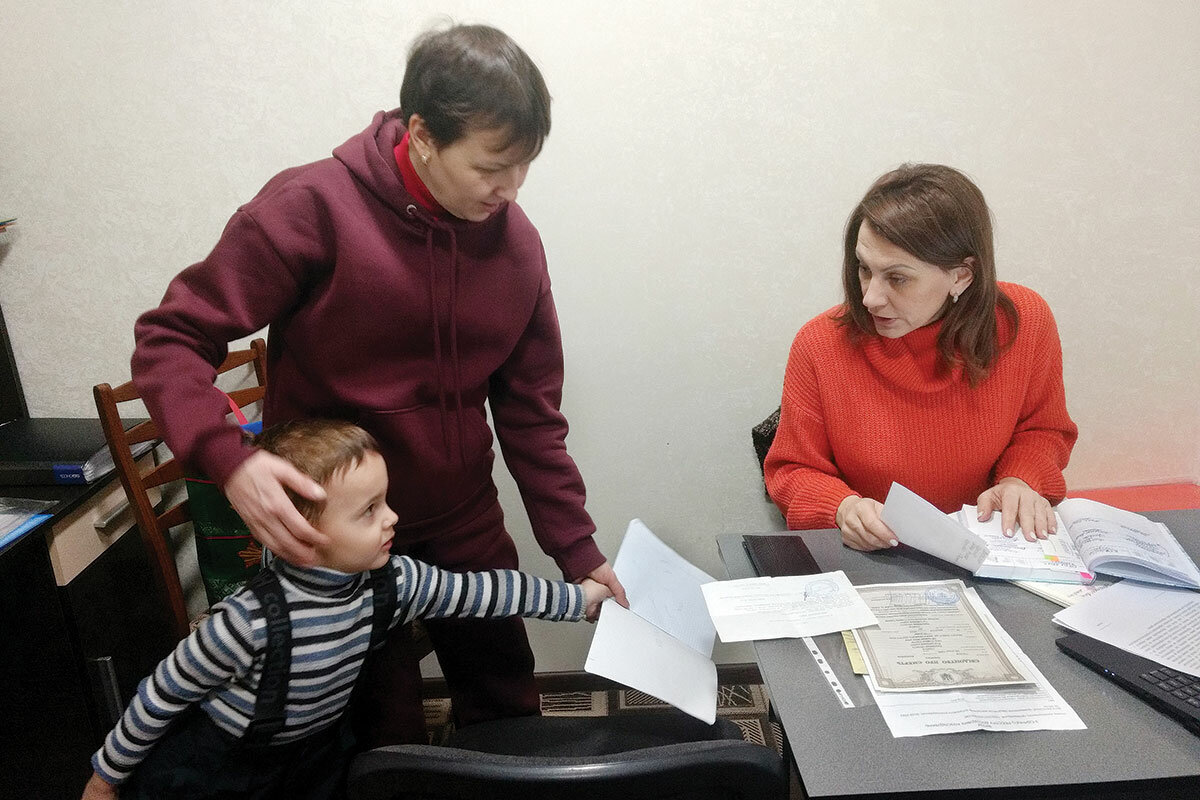

Natalia Rudenko arrives at the office on an ashen February morning with her young son, Egor, to share an account of wartime terror spanning three generations. A year earlier, as Russian troops surged over the border and bombarded Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, mother and child found refuge in the basement of an apartment building near their home.

They lived underground for the next three weeks, their days and nights splintered by the ceaseless sounds of war above. Venturing outside in March, Ms. Rudenko, whose husband volunteered in the country’s territorial defense force, discovered that an artillery shell had damaged their home.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn Ukraine, remembering does more than honor those lost in the war. It charts a path forward to a future free of Russia.

She packed two suitcases and traveled with Egor by train to the western city of Lviv to stay with a relative’s friend. The distance from the fighting eased her anxiety without subduing her concern for loved ones left behind.

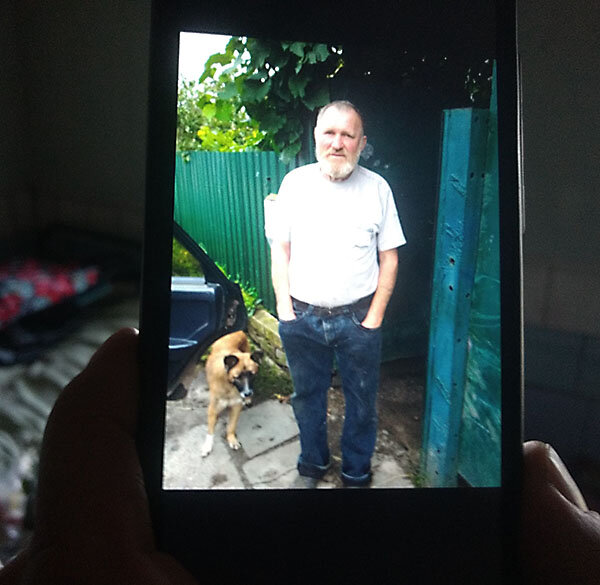

Soon after invading, the Russian military captured Ms. Rudenko’s hometown of Staryi Saltiv, a summer resort destination 25 miles from Kharkiv and half that far from Russia. Her parents, Tatiana and Yuri, who still lived in the house where she grew up, resisted her pleas to evacuate.

In early May, facing a Ukrainian counteroffensive, Russian forces pummeled the area with artillery to cover their retreat. Yuri and Tatiana, eager to tell their daughter about the town’s liberation, walked from their home to the top of a small rise in search of a cell signal. The call failed to connect. As the couple descended the hill, a rocket blast killed them.

Ms. Rudenko, a grocery store manager before the war, returned to Kharkiv in January and reunited with her husband. The dark circles beneath her eyes attest to an unrelieved sorrow that she attempts to conceal from Egor.

Since the weeks underground, he trembles with fear at loud noises, and his erratic moods often eclipse his playful demeanor, suggesting a young mind traumatized. She worries the war has claimed her parents and her son in different ways. She needs the world to remember.

“My mother and father are gone forever. But I want Egor to grow up in peace in Ukraine,” she says. Her head drops as tears fall. “I want everyone to know what Russia has done.”

The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group gathers testimony and evidence for referral to prosecutors investigating potential war crimes. The work represents one facet of Ukraine’s efforts to preserve memories of Russia’s unprovoked war and honor the dignity of its victims, living and dead.

The varied approaches – from formal actions of civic institutions to private vigils of everyday Ukrainians – embody a collective act of remembrance that also advances Ukraine’s ambition to pursue a future free of Moscow’s grasp. Beyond its military’s tenacity, the country has fought to counter Russian President Vladimir Putin’s parallel war on history, seeking to thwart him from silencing the Ukrainian idea.

“Memory is the foundation of our culture, our identity,” says Hanna Yarmish, the education director at a museum dedicated to the 18th-century philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda. A missile strike gutted the institution outside Kharkiv last May. “The memories of this war will mean that every future generation will understand what Ukraine represents, what Russia represents – and why Ukrainians will always choose freedom.”

Their resolve to never forget Moscow’s brutality exemplifies a desire to escape the Russian tyranny that for centuries stifled Ukraine’s distinct heritage, history, language, and identity. Starting in the mid-1600s, when the Russian Empire began conquering Ukrainian territory and branded its people “Little Russians,” Kremlin rulers at once dictated and disfigured the country’s future.

Vladimir Lenin codified Russia’s hegemony over Ukraine after quelling its fight for independence, absorbing the smaller nation into his newly formed Soviet Union in 1922. His successor, Josef Stalin, killed millions of Ukrainians in a decadeslong reign that brought the state-imposed famine known as the Holodomor, forced-labor camps, and mass purges, along with conscription into the Red Army.

The depths of Russia’s oppression drew into clearer focus only after the Soviet Union imploded in 1991. Less than a decade later, Mr. Putin ascended to power, and in the ensuing years, rather than redress past atrocities or build a stable alliance between the countries, he fixated on Russia reasserting control over Ukraine.

A popular uprising in 2014 ousted Ukraine’s then-president, Viktor Yanukovych, widely perceived as a Kremlin pawn. Mr. Putin responded by annexing the Crimean Peninsula and backing Russian operatives who seized portions of the Donbas region in southeastern Ukraine.

The land grabs portended the full-scale war he launched 14 months ago during the centennial year of the Soviet Union’s founding and three decades after Ukraine gained its independence. In a televised address days before the invasion, Mr. Putin mythologized his nation’s imperialism, describing Ukraine as “entirely created by Russia” and “an inalienable part of our own history, culture, and spiritual space.”

Mr. Putin’s bloody crusade to elide the national narrative of a sovereign Ukraine recalls the dark methods of Stalin, Lenin, and earlier Russian leaders to inflict a forced forgetting. His strategy to weaponize memory has fortified the solidarity of Ukraine’s people, whose united defiance evokes the struggle of their forebears and illuminates an indelible new history that belongs wholly to Ukraine.

“We must talk and be heard,” says Oksana Mandryka, an attorney with the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. “Under the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire, we couldn’t tell our story because we weren’t allowed to exist as a separate people. Telling stories – and remembering them – is how we will keep our spirit alive.”

Dappled sunlight falls across a forest cemetery where snow frames hundreds of empty graves. Wooden crosses bearing numbers in black ink stand inside the dirt plots. The dead have been removed. Their absence persists for those who loved them.

Russian troops captured Izium last April after a weekslong assault that damaged or destroyed three-fourths of the homes in the city of 46,000 people southeast of Kharkiv. A single airstrike on an apartment building killed 54 residents.

The Ukrainian army reclaimed Izium in September, exposing the horrors of the occupation. The Russians dumped some 450 bodies into the crude graves that now lay bare. Most of the dead were civilians; many showed signs of torture. A mass burial pit contained the remains of 17 Ukrainian soldiers.

Officials exhumed the victims to begin the arduous process of identifying them. Several who were congregants at Holy Ascension Cathedral, a Ukrainian Orthodox church, have received formal reburial in the same cemetery. On this cloudless afternoon, beneath a gossamer canopy of pine trees, archpriest Bogdan Dumindiak has finished a graveside service for a grandmother killed in the apartment attack.

The invasion has expanded his perspective on the symbolism of burial rites. “It is now not only personal and spiritual,” he says. “It is also historical.” He seeks to reassure bereaved survivors that their lost loved ones live forever in the national memory.

“We must remember each individual for the family and for Ukraine,” Father Dumindiak says. He wears a parka over his vestments against the cold, his manner as quiet as the woods around him. “They would be part of our future if not for Russia.”

The empty grave marked with cross No. 76 once held the body of Olena Shevchenko’s daughter, one of the 8,490 civilian deaths as of mid-April that the United Nations has recorded in Ukraine since Russia invaded.

Victoria Redko brought a homemade meal to her mother almost every Wednesday for decades. She prepared containers of borscht, dumplings, or potato pancakes before walking the mile to her childhood home.

As Russian forces attacked Izium last spring, Ms. Redko worried about her mother, a pensioner and widow who lives alone. Unable to contact her – the city lacked power and cell service – Ms. Redko decided to keep their weekly lunch date. She filled two tote bags with food and set out on the second Wednesday in March.

She never arrived. Ms. Shevchenko’s younger daughter later braved the Russian shelling to drive to her sister’s home and learned the worst from a neighbor. An artillery blast killed Ms. Redko as she walked to her mother’s house.

Ms. Shevchenko wipes away tears while sitting in the kitchen where she and her elder daughter had talked and laughed. An artificial rose in a vase on the table honors the memory of Ms. Redko, the mother of two adult sons. “I have a sadness that is deeper than anything I have ever felt,” she says.

A child of the Soviet Union, Ms. Shevchenko speaks Russian, the dominant language in eastern Ukraine. Before the war, the region shared a strong kinship with Russia, rooted in family, religion, culture, and history. Two of her paternal uncles served in the Red Army during WWII as the Soviet Union fought to liberate Ukraine from German occupation. Her mother recalled Soviet soldiers handing out bread to hungry families.

Three generations later, Ms. Shevchenko’s youngest grandchild – one of Ms. Redko’s sons – wears the uniform of the Ukrainian army. His unit took part in the counteroffensive that drove Russian troops from most of the Kharkiv region last fall.

“Putin calls us ‘one people.’ It was always a lie,” she says. “But in Soviet times, we thought Russia was against fascism. Now Russians are the fascists. We will always remember this aggression.”

Ms. Shevchenko still talks with her daughter every Wednesday when she visits Ms. Redko’s grave in the forest cemetery where the family reburied her after Russian troops retreated. More than 100 bodies that officials disinterred in September remain unidentified. Father Dumindiak struggles to find meaning in the country’s torment.

“We carry this sadness in our hearts,” he says. A low rumble drifts through the woods from a nearby road as flatbed trucks haul Ukrainian tanks toward the besieged city of Bakhmut. War has taught him that the pain of memory is the price of sovereignty.

“With God’s help, we will stay free. We will try to forgive,” he says. “But it is not possible to forget.”

The security guard stepped outside to take a call a little before 11 p.m. He knew the thick building walls would interfere with cell reception. He had no inkling the decision would save his life.

Moments later, a missile slammed through the roof of the National Literary Memorial Museum of H.S. Skovoroda. The impact blew out the windows and ignited a fire that consumed the interior. Rescue workers found the security guard pinned under debris, injured but alive.

Hanna Yarmish, the museum’s education director, views his survival as a metaphor for the resilience of Ukrainian culture as epitomized by the lasting influence of Hryhorii Skovoroda. “In the same way that you cannot extinguish the memory of Skovoroda,” she says, “you cannot extinguish the Ukrainian idea.”

Snow crunches under her boots as she walks through the ruined museum on the estate grounds where the “philosopher of the heart” spent his final years before his death in 1794. Missile fragments from the attack last May dangle in tree branches above the missing roof.

“You can destroy some buildings, some monuments. But the physical is not the essence of who we are,” Ms. Yarmish says. She invokes Skovoroda’s tenet that meaning resides within human thought, spirit, and will. “The museum is still here because” – she taps her heart – “Skovoroda is here.”

Russia’s military has bombed 1,600 museums, cathedrals, memorials, and other cultural sites across Ukraine and looted tens of thousands of artworks and artifacts. As with the Skovoroda museum, located in a village of fewer than 600 people near Kharkiv, many of the strikes have occurred in isolated areas without discernible military value.

The rocket that hit the museum marks the sole attack to date on Skovorodynivka, the rural enclave named for the philosopher, whose writings explored themes of individual freedom, spiritual understanding, and the benevolent pursuit of happiness. Mr. Putin appears familiar with his work, if less so his ethos of compassion.

Two years ago, the Kremlin website posted a rambling essay credited to the Russian president and titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” Denying the existence of a unique Ukrainian culture and identity, the piece argued that Russia held equal claim to the legacies of Skovoroda, Taras Shevchenko, and Ivan Kotlyarevsky, three of Ukraine’s brightest literary lights.

Ms. Yarmish considers the museum attack a microcosm of Mr. Putin’s failed effort to redact by force Ukraine’s cultural history. The staff removed almost the entire museum collection soon after Russia invaded, preserving for posterity the tangible evidence of Skovoroda’s Ukrainian heritage.

At the same time, the bombing has infused his writings with renewed relevance in Ukraine, as President Volodymyr Zelenskyy made explicit during a Victory Day address last May.

The annual holiday commemorates the Soviet Union’s defeat of Germany in WWII. Mr. Zelenskyy mentioned the museum attack from three days earlier and quoted Skovoroda in condemning Russia’s invasion: “There is nothing more dangerous than an insidious enemy, but there is nothing more poisonous than a feigned friend.”

Mr. Zelenskyy denounced the “barbarians who shell the Skovoroda museum and believe that their missiles can destroy our philosophy,” and he vowed that “we will not give anyone a single piece of our history.” Ms. Yarmish voices similar conviction as she steps out of the scorched museum and descends its front steps, a Ukrainian flag waving in the breeze above her.

“From the first day the war is over,” she says, “the museum will be open.”

Vasily Hrushka worked the land for most of his life and the land always gave back. He trusted the rich, black soil in the fields where he sowed and harvested crops, earning the modest living that supported his family.

It was when war came to Kamianka that the earth betrayed him. Russian forces occupied the village nestled in a shallow valley outside Izium for six months starting last spring. The area marked part of the front line, and as heavy shelling damaged or destroyed every single home and residents fled, Kamianka’s population plunged from 1,000 to below 50.

Rockets twice hit Mr. Hrushka’s house. He rolls up his sweater sleeve above the elbow to reveal a scar the size of a silver dollar from a chunk of shrapnel. He points to another scar on his forehead and shares the story of a drunken Russian soldier who entered his home and struck him with the butt of a Kalashnikov rifle.

He healed from those injuries but endured a third after the Russians withdrew. The invading troops left discarded ammunition boxes, live artillery shells, incinerated tanks, and other war detritus throughout the village. In October, as he cleared debris from his fields, a mine buried in the soil exploded. His left foot was gone.

Mr. Hrushka recounts his misfortune without self-pity as he sits on a bed in his living room, crutches on the floor below him. His pale blue eyes pool with tears only when he describes the devastation of war. Homes reduced to ashes. The screams of farm animals ripped open by artillery. A neighbor sprawled dead in his yard, face turned toward the sky.

“This is what Russia has given us,” he says. He holds up a callused hand to correct himself. “This is what Russia has taken from us.”

The invasion has forced 14 million Ukrainians from their homes, and officials have logged more than 76,000 alleged war crimes committed by Russian soldiers. The list includes summary executions, torture, sexual violence, and destruction of civilian homes and infrastructure. In March, the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for Mr. Putin’s arrest, implicating him in the mass abduction and deportation of Ukrainian children.

The incalculable trauma wrought by the invasion will trail Ukrainians for generations. “Our bodies right now are clenched like a fist,” says Natalya Potseluyeva, a psychologist who treats survivors of war crimes. “Everybody in the country feels this way to different degrees.”

Ms. Potseluyeva counsels people to accept that the war lies beyond their control and to focus on finding daily purpose even with missiles falling. She tells them that defusing memories of Russia’s cruelty will require time and talking.

“We can’t simply forget this destruction being done to us. So we must learn how to speak about these things to understand our trauma,” she says. “This will allow us to think about our future again.”

The date of Feb. 24, 2022, will forever represent a watershed in Ukraine. The day Mr. Putin unleashed his wider invasion arrived 31 years after the country declared its independence from the Soviet Union on Aug. 24, 1991. His decision demarcated in blood the moment Ukrainian identity slipped free from Russian history.

Another date from last year shadows Mr. Hrushka – Oct. 19, when the earth erupted beneath him. He has lost much to Russia, yet like his homeland, he chooses to look ahead. He expects to receive a prosthetic foot in the coming months, and in time, he plans to resume working in his fields.

In the war’s first days, as rockets rained on Kamianka, Mr. Hrushka and his wife prepared to flee. He set free the cows, goats, and pigs in his barn so they might escape slaughter by the Russians. When he checked on the house a few days later, the animals had returned. He saw in their behavior a reflection of Ukraine’s indomitable memory.

“This is home. They remember,” he says. His eyes shine as he smiles. “We remember.”