Do new border checks threaten Europe's free movement? Not yet.

Loading...

| Paris

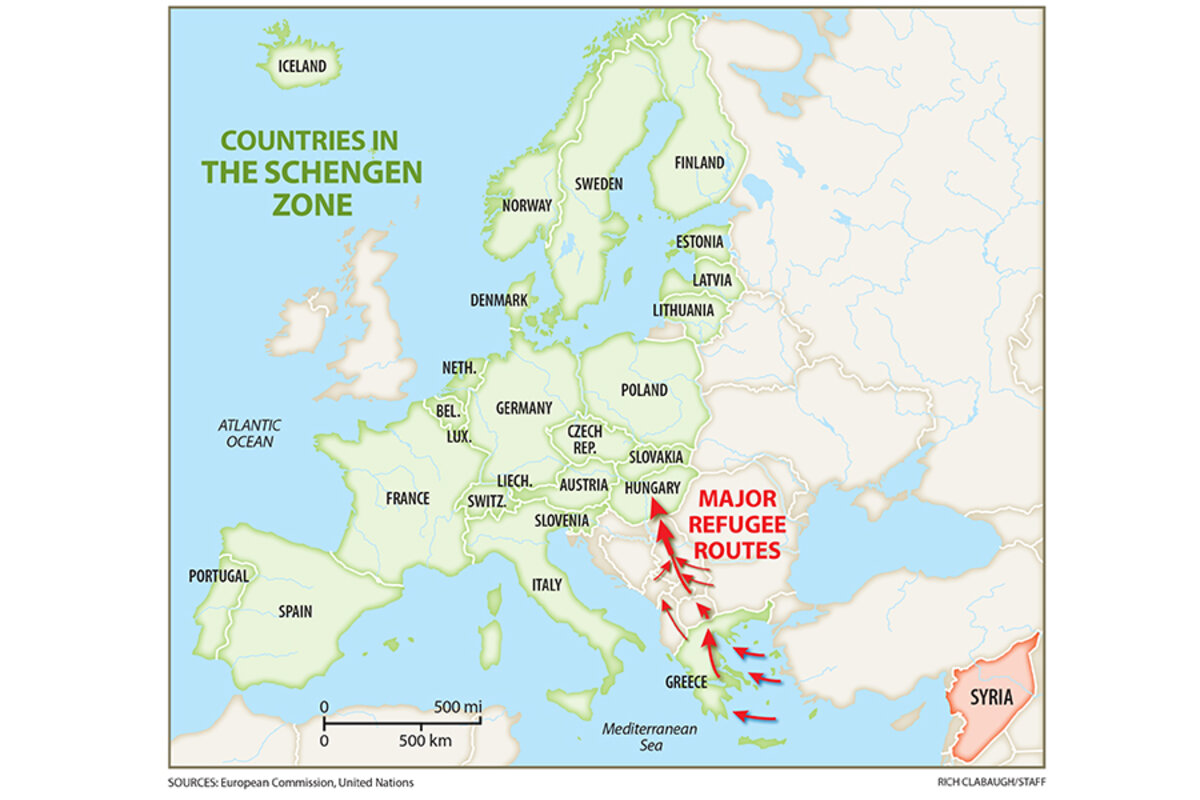

With the European Union’s failure to force members to accept a mandatory quota for refugees, officials have said that borderless travel, one of the continent’s flagship achievements, may be at risk.

In reality, such seamless movement, prescribed under the Schengen accord, is likely to stay the norm for the foreseeable future – and for the vast majority of travelers within the 26-nation Schengen zone.

Germany’s decision on Sunday to temporarily impose border checks on its frontier with Austria was prompted by the record influx of asylum seekers pouring through Munich’s central train station for the past two weeks. Thirteen thousand arrived on Saturday alone.

The move was also viewed as tactical, to force resistant EU members, mostly in the east, to accept their responsibility in giving refuge to those fleeing war. Instead it caused Austria, Slovakia, and the Netherlands to say they would start patrolling their own borders. And now, with no robust EU plan in place for the record number of refugees coming into the bloc, other countries are studying whether they need to impose emergency controls as well.

That has spurred some to warn that the "death" of Schengen, which was signed in 1985 and has been in operation for 20 years, is near. European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s chief of staff tweeted on Sunday: "Schengen will be in danger if EU member states don't work together swiftly and with solidarity on managing the refugee crisis."

Pining for the fjords?

But there are several reasons why it’s likely to withstand the pressure – at least for now.

- The kinds of controls being implemented today, though unprecedented in scale, were envisioned when the zone, which includes 22 EU members as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, and Norway, was formed. If members see “a serious threat to public policy or international security,” they can put up controls temporarily.

- This is not the first time such controls have been put in place. They’ve also been imposed during summits, including the Group of Seven in Germany this year and sports events, to bolster security.

-

Such temporary measures are not likely to impact the majority of travelers, either, since borders are not actually closed down. Rather, there are spot checks at certain crossings – though that might imply a certain degree of racial profiling, as they are seeking to control those fleeing war or poverty in Africa and the Middle East.

Measures of this type aren't allowed to last more than 30 days without justification. And under Schengen, they cannot become routine.

- The move was not an act of panic that means the system is failing, says András Rácz, senior research fellow at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs. While Germany’s move was prompted by an overwhelming influx, “I don’t think Germany would have collapsed under the pressure of asylum seekers,” he says. “They are not overburdening Germany as a whole.”

Many don’t see Schengen as the problem, either – rather, they view it as a symptom and a scapegoat. The system seen in greater need of repair is the so-called "Dublin regulation," a policy that mandates asylum seekers to register in the first EU country that they enter.

But it is borderless travel that’s come most under fire this year, and not just from the migration crisis. The question of European jihadis, who can travel freely from their home countries around the Schengen zone, has fueled many to ask whether its benefits outweigh the risks.

The cost of replacing Schengen

Nonetheless, in many cases getting rid of Schengen doesn’t solve the core problems. Terrorism is a threat to countries inside and outside the Schengen zone, including Britain. And while passport checks are eliminated under Schengen, national police forces can still check travelers.

Such controls are generally considered an acceptable cost for Schengen freedoms, which are loved – and taken for granted – in Europe. Some 1.25 billion journeys are made a year within the zone, involving 400 million citizens, as well as business travelers and tourists.

Revoking Schengen would require setting up passport controls, staff, and equipment – a price that most nations wouldn’t be willing to assume. Costs to businesses, with trucks waiting in lines at borders, would also be exorbitant. Nor would many people, accustomed to traveling abroad without passports or the hassles of passport checks, willingly let go of such perks.

“The population is also Schengen socialized,” says Mr. Racz.

Still, heavy flows of asylum seekers are not going to dissipate. This summer has set records, and while winter will reduce the numbers temporarily, the migration trail will likely fill up again in the spring due to all the intractable conflicts in the Middle East and elsewhere.

“I think this is a very dramatic episode, but just the beginning of a long-term problem,” says James Davis, director of the Institute of Political Science at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland. He argues that Europe needs both a common policy on refugees and a plan to stop the flow of economic migrants. Otherwise controls will continue to be imposed, and Europeans, despite themselves, might just get used to them.

“If we don’t get a European common approach to these questions by end of next year, Schengen is dead.”