Volunteers rush to aid migrants in Europe – but will the goodwill last?

Loading...

| Budapest, Hungary

Budapest's Keleti train station last week looked more like a war zone than the elegant transport hub of a tranquil European capital. It lay surrounded by some 3,000 refugees, stranded there for days amid hope they might resume their travels to Germany.

Zoltan, a Hungarian law student, moved amid the overpowering masses, getting grabbed every few seconds by a needy hand. As a member of Migration Aid, he was helping organize and feed the hungry whenever food was available.

“I can’t believe these people can’t fit anywhere,” said Zoltan, declining to give his last name. “There is chaos within the international community and no one is doing anything for these people. Someone must act quickly before the problem becomes bigger.”

To most of the migrants who had trekked for days to arrive there, he was one of very few people they could expect some attention from. But that is changing.

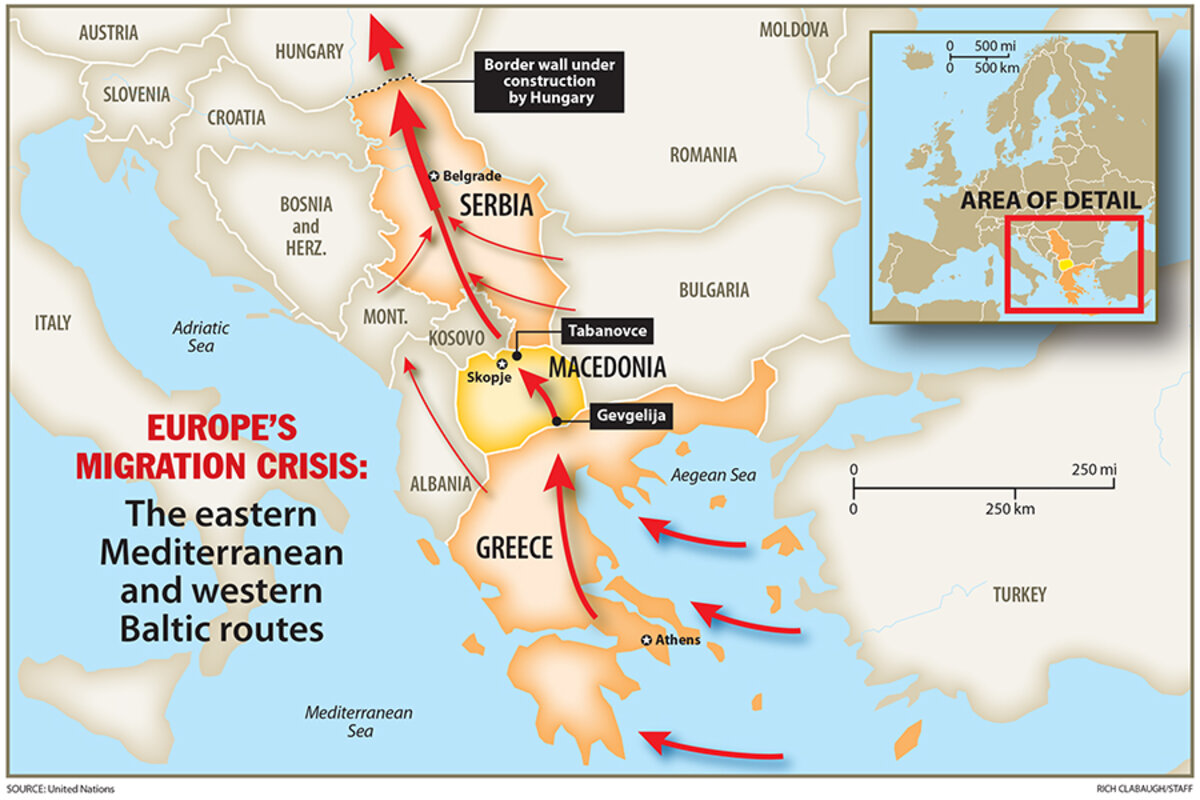

The unprecedented number of migrants in the European refugee crisis is being met by an equally unprecedented response from European civilians who are trying to alleviate the situation. From nurses in Greece to housing volunteers in Germany and travel assistants in Macedonia, people are spontaneously stepping in to aid the tens of thousands fleeing war-torn Syria and other countries.

But whether the surge in volunteerism persists remains to be seen. Many people, particularly in southern and eastern Europe, have responded with an activism rarely seen in their countries – but may lack the long-haul energy and resources to sustain it.

Hungarian aid

More than 332,000 migrants have crossed from the Middle East and Africa into Europe this year, according to the International Organization for Migration. Greece, Italy, and Hungary have been the front-line states through which migrants enter the European Union, and, in many cases, stay for days.

In Hungary, the number of refugees has jumped from 2,000 in 2012 to 150,000 this year, says Camille Tournebize of Migrant Solidarity Group of Hungary, a group that was formed three years ago to assist Afghan asylum-seekers with legal procedures. That 150,000 does not include those who have entered Hungary without getting registered.

Prime Minister Viktor Orban's government has been either unwilling or unable to help the refugees arriving daily. And Hungary, as part of the ex-Communist bloc that saw civil society interrupted for more than four decades, has little history or experience with the sort of volunteerism that is fostered in more established democracies.

But amid the crisis, volunteers are stepping forward. Migration Aid runs a daily list on its Facebook page of goods that are needed, from fruits to blankets to baby food. The response has been such that in many days the group has had to update their posts to ask people to stop donations.

When migrants started arriving en masse to Szeged, a city in the southeast near the Serbian border, five local citizens took notice of the lack of any support. So they founded MigSzol Szeged, which provides refugees with warm clothing, food, and assistance in filing papers – aid that the government did not provide.

Similar action groups started popping up independently, even in countries like Macedonia, which has little experience with immigrants.

Embracing the migrants

Greece is another “low” volunteerism country, per a 2010 report by the European Commission. In the Mediterranean country, less than 10 percent of the population is involved in formal volunteering. That compares to more than 40 percent in the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden, and Britain.

But this year, Greece has received more refugees than any other country in Europe, even as it is undergoing a deep economic recession and political instability (it will have its second general election of the year this month). That has forced the state to withdraw much of its aid – and prompted volunteers to try to fill in the gaps.

In the Greek island of Lesvos, close to Turkey, four men created Angalia, which means "hug." They have provided shelter, medicine, and food to more than 7,000 migrants in the past three months, drawing on donations and help from locals and tourists. Similar groups have sprung up on the island of Kos and in the northern city of Thessaloniki, en route to Macedonia.

This volunteerism could spur Greeks to greater civic participation in the future, says Dimitri Sotiropoulos, associate professor of political science and public administration at the University of Athens.

“Civic associations have stepped in to do what the state wasn’t able to do,” he says. “Because of the economic crisis, Greeks who have traditionally believed they should always turn to the state for help, have now realized that at crucial moments one has to create relationships with other people and engage in self mobilization. This is a big shift in mentality.”

'Not sustainable'?

But whether that shift sticks is another matter.

The obstacles to greater civic participation are a lack of funding in austerity-hit countries and a restrictive political environment in countries like Hungary, said Gabriella Civico, director of the European Volunteer Centre in Brussels, a network of volunteer groups.

“It is great that citizens are stepping up, but it also shows there is very low capacity to incorporate this number of volunteers,” said Ms. Civico. “What you are seeing is spontaneous volunteering that is not sustainable in the long term due to lack of funding and support for volunteering infrastructure.”

Still, volunteers like Ms. Tournebize remain optimistic. She believes the momentum created by social participation in Hungary will likely last or be channeled into other things. “There has been a huge change, with more groups created and becoming more visible,” she says. “So many people got organized that this spirit cannot just got away.”