Seeking Refuge: Five lessons from Europe's migration crisis

Loading...

| Paris

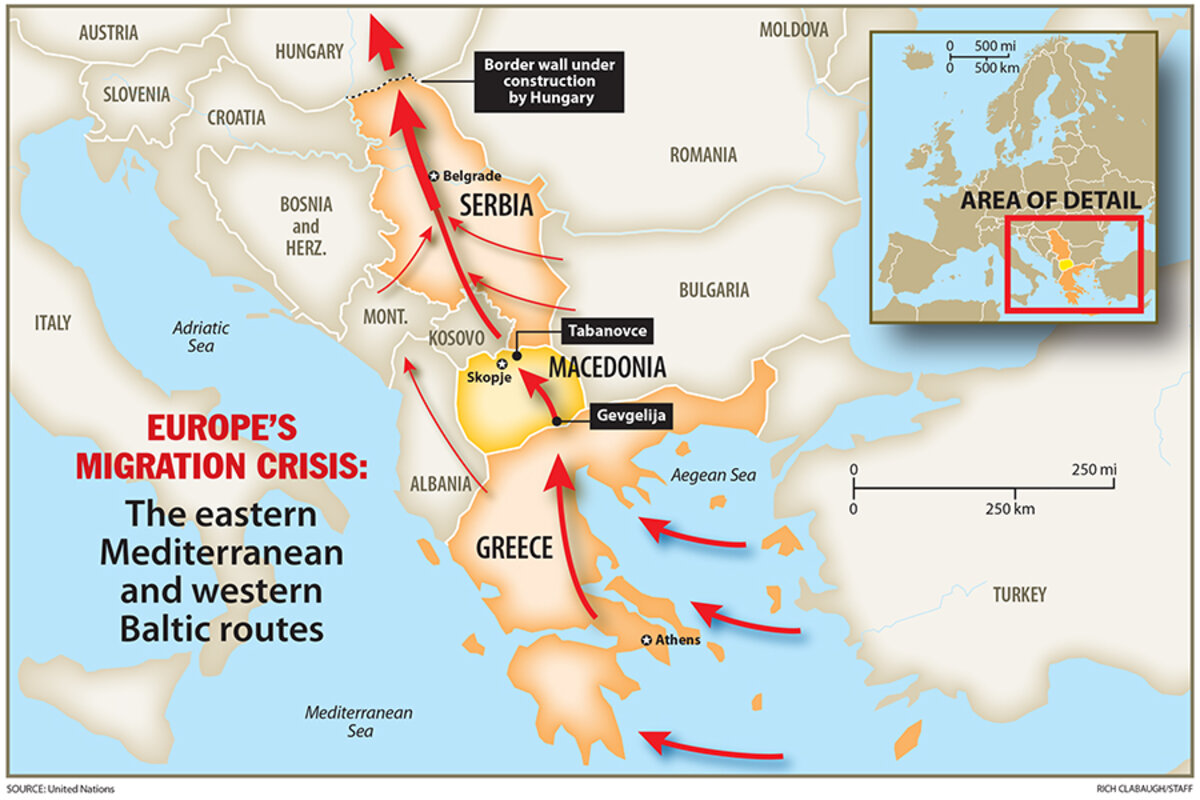

Europe is experiencing the largest movement of people across its borders since World War II, and it is struggling. It’s not just wrestling with capacity and enforcement, as the crush of Middle Easterners and Africans take to the Mediterranean and trek across frontiers, but also testing the limits of its humanitarianism.

The human tide has weighed heavily on some countries and inundated swaths of European countryside or urban space – eliciting fortitude and generosity of spirit, which has been undercovered. It has also revealed a dark side to the continent: fences, tear gas, riots, and hate speech.

Today’s migrants are as poor or traumatized as those refugees during World War II, but many are also black or Muslim. They stand out in communities that have long known nothing but homogeneity. And they are entering at a time when EU citizens question what it really means to live in the 28-member union.

These questions have been brewing for years, but the sheer scale of migration has thrust them suddenly from abstract scenarios into a situation demanding answers now. Through July of this year, some 340,000 have attempted to reach Europe’s doorstep according to EU statistics, nearly three times the same period of last year. And so far nearly 2,440 have died trying.

In an ongoing series called Seeking Refuge, the Monitor has searched for themes and lessons learned in the midst of one of the European Union's greatest modern tests.

1. Migrants will keep coming

When a boat capsized in April off of Libya, killing nearly 800 migrants on board, the argument that the EU should scale back patrols to deter migration – as they were doing at the time of the tragedy – was flipped on its head.

Rescue patrols and walls factor into a migrant’s choices to attempt the trip, but it doesn’t deter his or her decision to leave war or poverty. Life is still better in Europe.

That has been put in sharp focus in Greece. We kicked off the series on the island of Kos, where migrants were steadily streaming in amid an economic crisis that sapped the Greek state's capacity – or appetite – to house and care for thousands of newcomers. Since then tens of thousands have arrived anyway, with 21,000 showing up in one week in August alone.

2. Much of Europe see the migrants as 'the other guy's' problem

Greece and Italy face the physical crush of arrivals, while Germany, Sweden, and Britain are where most migrants want to go. Germany announced this week that it expects 750,000 asylum claims this year, four times more than last year.

Yet in between are nearly two dozen countries that do not see migration as their problem. An EU plan to relocate and resettle some 60,000 migrants has sent much of Europe into an emotional tailspin. One of the countries feeling the brunt of criticism for not doing its part is Britain.

Central and Eastern Europe, meanwhile, which have almost no experience with this type of migration, condemned Brussels for placing a burden on their shoulders where they say it doesn’t belong – even though emigration has long been that region's only escape valve. In the end, a broad, mandatory relocation plan was torpedoed in favor of a smaller, voluntary one – which nonetheless continues to rile.

"There is no incentive for central European countries to accept relocation. They don’t see it as their problem,” said Elizabeth Collett, director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe in Brussels.

3. Europe's migration system is not working

For all of the anger directed at Brussels, critics make a valid point too. Europe's system for accepting migrants doesn’t work. The policy that’s been most tested is the Dublin Regulation, the European treaty that stipulates that refugees must have their asylum applications processed by the EU country they first set foot in. Though the convention is meant to be mandatory, overloaded periphery countries are turning a blind eye to the migrants who wish to move on, as virtually all do.

So the migrants easily leave, and take advantage of another European rule that applies to most countries in the bloc: the passport-free Schengen zone.

Earlier in the summer, France started checking passports at its frontier with Italy to dissuade migrants from entering – a violation of Schengen rules, particularly as it happened just as Europeans kicked off the summer vacation season.

“This is a much wider problem than Schengen, but Schengen is the victim because it becomes a symbol of all the fears, that we are defenseless,” explained Marc Pierini, a visiting scholar on European policy at Carnegie Europe in Brussels.

Now many of those same migrants who crossed the Italian-French border are amassing in Calais, at France’s northern edge. This time they face a harder task moving onto their final destination, Britain, both because of geography and because Britain is not part of Schengen. Thousands have stormed the Eurotunnel this summer, leaving at least nine dead.

4. Some Europeans have been magnanimous

This migration crisis has given a high-profile platform to xenophobia. It has led Hungary, where numbers of migrants entering has dramatically spiked, to start building a wall. The Slovakian government said it would accept refugees from Syria but only Christian ones, not Muslims.

And yet, there are European citizens who are trying to rise above the fear. As the newest flashpoint has appeared in the Balkans, at Greece’s border with Macedonia, authorities have tried to keep them back with batons. Meanwhile, one group waits for their arrival – with supplies.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Gabriela Andreevska, a young Macedonian who spends most nights at the border, helping the migrants trying to reach the EU. “So many people sleeping on concrete. They’re there, and you can’t turn a blind eye.”

5. The 'migrant crisis' is a human crisis

In the heated discussion about Europe’s migration crisis, which can bleed into the wider debate over security and terrorism, it’s easy to forget the most important lesson of all. Each migrant is a person, with families back home and a lifetime of aspiration and regret behind him or her.

The Monitor captured the human element by following the path of two Syrians through Europe’s borders until they finally reached northern Europe. Living in a tidy apartment in Germany, well-housed and fed and nearly guaranteed to be granted refugee status, one of them was still anxious; his mother and sister were still in war-ravaged Syria.

“I want to bring my family, and I’m just wasting time,” he said. “I don’t want to see one of them in [the news] someday.”