Will walls really help reduce Europe's migration crisis?

Loading...

| Paris

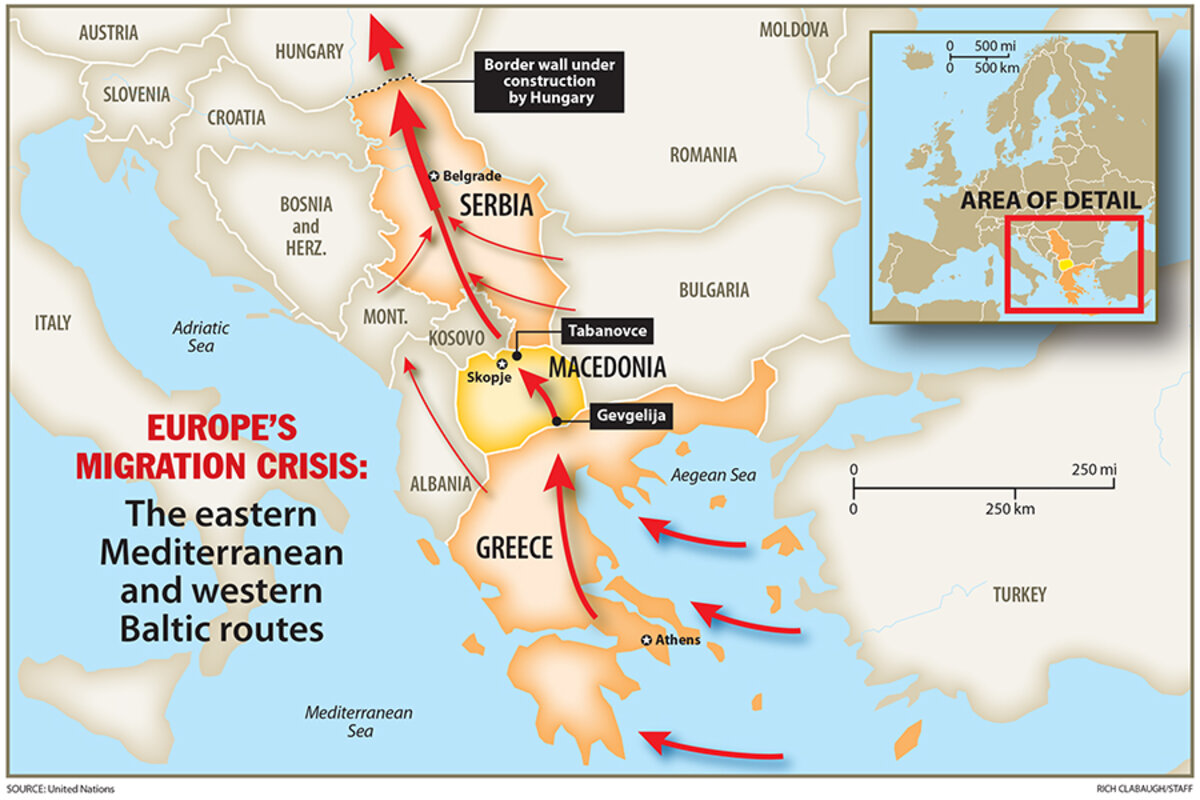

With Hungary just days away from completing a nearly 109-mile wall along its border with Serbia, tens of thousands of refugees have been rushing north through the Balkans before the way is closed off.

Hungary's aim is clear: to block the flow of refugees taking the increasingly popular Western Balkan Route – even if their ultimate goal is to reach the Netherlands, Germany, or Britain.

But as walls, fences, and other barriers go up to stem migration not just into Hungary, but into Europe generally, critics question their effectiveness in keeping people out.

For one thing, borders are expensive to build and maintain. But critics also argue that as one area becomes blocked off, other unprotected border areas and ports open become more vulnerable. The walls also risk pushing illegal traffickers to take advantage of refugees desperate to cross the Continent.

Hungary is just one of many European countries considering physical impediments to migration. Bulgaria has completed a 50-mile stretch of fencing on its border with Turkey to keep migrants out – just two decades after removing a wall designed to keep its citizens in. And in Calais in northern France, two razor-wire fences now encircle the Eurotunnel terminal – the result of a 7 million pound ($10.8 million) pledge by the British government to secure its border with France.

But “building a wall doesn’t deal with the demand issue, so you’re just replacing flows rather than reducing them,” says Elizabeth Collet, director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe in Brussels.

“Once the Hungarian fence is completed, people will be shifting to a different, possibly more dangerous, route in order to circumvent that, rather than deciding not to make that journey,” she says.

Already, Britain is in talks with Belgium and the Netherlands in anticipation of knock-on effects from the overwhelming number of border crossings at Calais. More illegal crossings have been reported in nearby Dunkirk on the French-Belgian border, and Zeebrugge in Belgium and the Hook of Holland also risk more illegal entries as Calais security is amped up.

Britain may have reason to worry. In 2012, Greece spent 3 million euros to build a 6.5-mile, 13-ft.-high barbed wire fence on its border with Turkey. Now, much of the migration flow has shifted to the sea border. The latest figures by the UNHCR show that more than 158,000 people arrived in Greece by sea from Jan. 1 to Aug. 14 of this year, compared with under 2,000 by land.

According to Frontex, the European border management agency, migration patterns tend to change very little, but the popularity of certain routes increases when one border becomes more secure and another less so. That can put migrants in greater danger, not only from the alternative routes but from illegal trafficking rings that they may turn to for help.

“If you’re pushing people to take more convoluted and dangerous journeys to reach a certain destination, effectively traffickers can charge higher prices to facilitate that journey,” says Ms. Collet. “So it actually plays into their business model. They can say, ‘now you need our help but it’s going to cost you.’ ”

And the smugglers themselves could be dangerous, as indicated by today's discovery of at least 20 people – and possibly as many as 50 – apparently suffocated in an abandoned truck in Austria. Authorities say they believe the victims were migrants being smuggled into the EU by a trafficker who abandoned the truck.

For many refugees, one more wall is not going to stop them given a journey that has already been long and treacherous.

“These people have crossed the Mediterranean on a boat, or walked across the desert. These walls have little effect on them,” says Christian Salomé, president of the Calais-based nonprofit L’Auberge des Migrants, which works with the some 3,000 people living temporarily at “The Jungle” immigration camp. “Most are completely determined to cross, and they’ll just find a way to get around it.”