In Pakistan, one embattled ex-PM gets bail, the other doesn’t. Why?

Loading...

| Islamabad

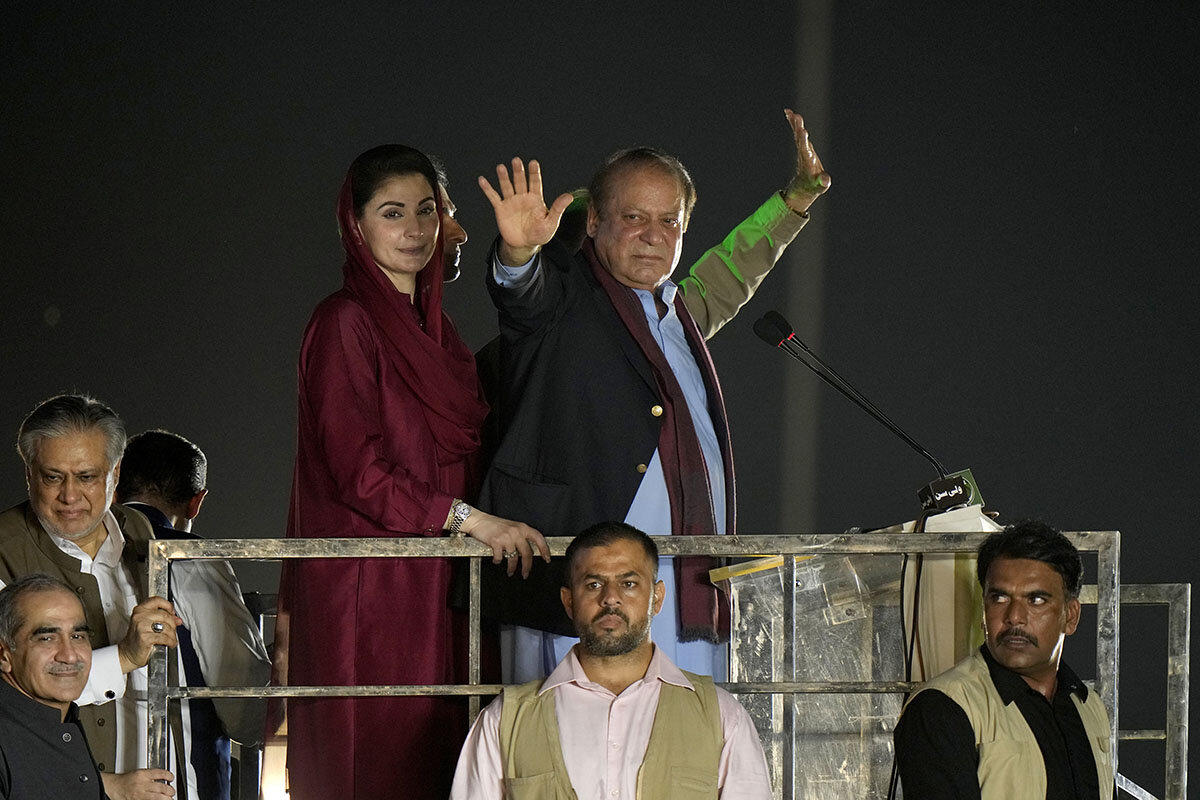

On Saturday, after almost four years of self-imposed exile in London, former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif addressed a large gathering of triumphant supporters in Lahore, promising to return Pakistan to its “former glory.”

His own return was made possible by authorities’ newfound leniency: Last week, Mr. Sharif was granted protective bail until Oct. 24, despite the fact that he had been sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment under Pakistan’s anti-corruption laws in July 2018. Meanwhile, Mr. Sharif’s successor and main political rival, Imran Khan, remains incarcerated as authorities investigate his handling of state secrets. That dichotomy highlights deeper issues of fairness in Pakistani politics, which have always been influenced by the country’s powerful military.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn Pakistan, two former prime ministers, both accused of corruption, are receiving different treatment from authorities. What does fairness look like in a case with so many missteps and injustices?

Observers believe Mr. Sharif is being drafted in as a foil to Mr. Khan, who was initially promoted by the army but eventually removed from office by a military-sponsored vote of no-confidence.

“The generals fall out with their latest protégé and then have to hurriedly draft in an older protégé ... to run the country,” says political commentator Cyril Almeida. “The only rule is to never let whoever is the most popular politician run the country lest he or she get ideas about actually being in charge.”

Former prime minister of Pakistan Nawaz Sharif touched down in Lahore on Saturday, after almost four years of self-imposed exile in London.

Mr. Sharif – who has thrice been elected prime minister and thrice removed from office before completing his term – left Pakistan in November 2019 to seek treatment for an autoimmune disorder, having been granted bail in two corruption cases that he has always maintained were politically motivated. With Pakistani politics in a state of limbo, the controversial figure has returned to spearhead his party’s campaign in the forthcoming general election.

On Saturday evening, Mr. Sharif addressed a large gathering of triumphant supporters in Lahore and promised to return Pakistan to its “former glory.” Political activist Gul Bukhari describes his return as a vindication. “You know all the generals and judges who collaborated to throw him out? It’s comeuppance for them,” she says.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn Pakistan, two former prime ministers, both accused of corruption, are receiving different treatment from authorities. What does fairness look like in a case with so many missteps and injustices?

Yet authorities’ relatively warm welcome of the ex-PM highlights deeper issues of fairness and integrity in Pakistan’s governance. Last week, Mr. Sharif was granted protective bail until Oct. 24, despite the fact that he had been sentenced to ten years imprisonment under Pakistan’s anti-corruption laws in July 2018. Meanwhile, Mr. Sharif’s main political rival, Imran Khan, remains incarcerated as authorities investigate his handling of state secrets. That dichotomy has many in Pakistan criticizing the country’s politicking military, with journalist Taha Siddiqui saying that the army’s interference has made a mockery of Pakistan’s political and judicial systems.

“The message is: if you are friends with the military in charge, you can do politics in the country and the cases against you will dissipate into thin air,” he says. “But if you disturb the military’s hegemony, you will rot in jail like Khan is doing, or in exile like Sharif did when he was a military critic.”

Caught in old cycles

Throughout its 76-year history, Pakistan has seen long periods of direct military rule. Mr. Sharif’s second government was deposed in a military coup in 1999, and his most recent term in office was marred by constant squabbles with the top brass of the armed forces.

Indeed, when Mr. Sharif was convicted of corruption in the run up to the 2018 general election, many saw his legal troubles as punishment for falling out with the country’s influential military, which disagreed, among other things, with Mr. Sharif’s desire to normalize relations with India.

Now, observers say he’s being drafted in as a foil to Mr. Khan, the cricketer-turned-politician who was initially promoted by the army, but eventually removed from office by a military-sponsored vote of no-confidence in April 2022. Mr. Khan and members of his PTI party face mounting legal challenges which will likely bar them from meaningfully participating in the next election.

“The courts have bent over backwards to give him [Mr. Sharif] relief in a couple of days before his arrival,” says Sayed Zulfiqar Bukhari, who served as a special assistant in Mr. Khan’s cabinet, “whereas Imran Khan and all of us that have frivolous charges against us can’t even get a date down on the register of the court. … In one way it’s laughable, really, what’s happening, but in another way we all predicted that this was part of the bigger plan.”

In November 2022, the outgoing chief of Pakistan’s army, Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa, vowed that the institution would confine itself to its constitutional role moving forward. Many view the circumstances surrounding Mr. Sharif’s return as further evidence that this promise is not being kept.

Rather, political commentator Cyril Almeida claims that Pakistan has returned to its “oldest politics.”

“The generals fall out with their latest protégé and then have to hurriedly draft in an older protégé … to run the country,” he says. “It’s tiresome and never works, because the only rule is to never let whoever is the most popular politician run the country lest he or she get ideas about actually being in charge.”

A new political landscape

Familiar military meddling notwithstanding, experts note that the Pakistan Mr. Sharif left in 2019 is markedly different from the one he returned to this weekend.

The Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz government, which Mr. Sharif headed from 2013 until his disqualification in 2017, oversaw a period of relative economic stability with single-digit inflation and growth rates that compared favorably to those achieved by its predecessor. After Mr. Khan fell out with the army, his government was replaced in 2022 by a coalition led by Mr. Sharif’s younger brother, Shehbaz Sharif, who presided over a sixteen-month economic meltdown. Annual inflation in 2022 was measured at just under 20% while the Pakistani rupee plummeted to as low as 306 against the U.S. dollar. Pakistan currently has a caretaker government as it awaits the next general election, slated for no later than February 2024.

“He [Mr. Sharif] comes back with the difficult task of uniting his party at a moment when it faces fissures and energizing his support base against the backdrop of a terrible economic crisis that has hit the public hard,” says Michael Kugelman, the director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington. “But with the military now having his back, there’s one less thing – one less big thing – for him and his party to worry about.”

Nor, it seems, will he have to worry about Mr. Khan. The government of Mr. Sharif’s younger brother, which suffered from accusations of nepotism throughout, found it difficult to counter the political messaging of Mr. Khan, who went on a nationwide speaking tour shortly after his removal and doubled down on his accusation that he had been removed by a “gang of crooks” in cahoots with the U.S.

It was a message that resonated more and more as the country’s economic crisis deepened and propelled Mr. Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), to a string of by-election victories in both the National Assembly and the large province of Punjab. However, in the aftermath of the May 9 riots – when a number of PTI supporters laid siege to military installations in response to Mr. Khan’s arrest – the military unleashed a brutal crackdown against Mr. Khan’s party and launched a full-throttle campaign to remove Mr. Khan from the political arena.

“The biggest argument in support of the idea that the election is already rigged, no matter what happens on Election Day, is the scale of the broader crackdown on Khan’s party,” says Mr. Kugelman. “Leaders jailed or forced to leave politics, arrests and intimidation of party supporters, bans on media coverage of Khan and his party, and so on. The election campaign may have started, but with the PTI cut down to size and hollowed out, there’s little chance of a level playing field.”

Even if Mr. Sharif manages to revive his party’s fortunes and form the next government, his mandate to govern will be limited by the illegitimacy of such an election.

“Imran’s term was dominated by the Nawaz question, Nawaz’s likely fourth term will be dominated by the Imran question,” says Mr. Almeida, the political commentator. “Pakistan seems destined to go around in circles.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the year that Mr. Khan was removed from office, and to clarify the nature of PTI’s by-election victories. The party won seats in national and local assemblies.