Free trade, openness, and democracy: Why China’s rhetoric mirrors America’s

Loading...

Days after the U.S. presidential election, as Donald Trump was basking at an America First Gala in Mar-a-Lago in Florida, Chinese leader Xi Jinping appeared some 2,600 miles due south, celebrating his own victory in America’s “backyard.”

In Lima, Peru, Mr. Xi was presiding virtually over the opening of a Chinese-built megaport at Chancay on Peru’s coast. The port is expected to transform regional trade by opening a fast, direct route from South America to China, promoting an “open and interconnected” Asia-Pacific, as Mr. Xi told world leaders in a speech the next day.

It struck a familiar chord, echoing how American leaders have described their vision for the region, including the U.S. strategy to promote a “free and open” Indo-Pacific that was launched in 2022.

Why We Wrote This

As Donald Trump takes office in the United States, China pitches itself as the new global leader – and for all the countries’ ideological differences, Beijing seem to be taking notes from Washington.

As part of a broader effort to displace the United States as the preeminent world power, Beijing has been increasingly appropriating language used by Western democracies to cast China as a responsible and stable leader defending the global order – in contrast with a U.S. that could grow rash and protectionist under Mr. Trump.

It’s not just that China is trying to boost its international image ahead of the inauguration. It’s also that it’s doing so by referencing openness and free trade, as well as Chinese-style democracy and human rights.

“They are co-opting ideas that have become very popular in the international community and made instrumental benefit to the Chinese,” says Thomas Fingar, a fellow at Stanford University’s Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center. Indeed, an “open and interconnected” world has served China’s own interests since the country opened its doors, broke with Maoist isolationism, and embraced a trade-fueled market economy in the 1980s.

“The Chinese are saying, ‘We are not revisionist; we are the defenders of the part of the status quo that works – it’s the Americans who are threatening to disrupt it,’” Dr. Fingar says. And that resonates in Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia where Beijing’s sway is growing.

An opportunity to flip the script

China’s inroads in South America, where it has supplanted the U.S. as the largest trading partner, show how Beijing under Mr. Xi is already challenging U.S. leadership – and will seek fresh chances to do so under the second Trump administration that begins Monday.

“China sees a new opportunity with the Trump administration,” says Elizabeth Economy, co-chair of the Program on the US, China, and the World at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. “China as the champion of free trade will at least have the opportunity to be heard,” she says, if Mr. Trump “levies tariffs on all of the U.S.’s trading partners.”

Indeed, China has anticipated the possibility of a Trump return for years, and is poised to take advantage of any leadership vacuum that Mr. Trump creates. For example, if Mr. Trump again pulls the U.S. out of the United Nations Human Rights Council, as he did in 2018, Beijing could advance its efforts to embed its state-centric definition of human rights in the U.N.

“The victory of Donald Trump” signals a shift in the U.S. from its 30-year “post-Cold War role as a leader in globalization ... toward more conservatism and unilateralism,” said Henry Huiyao Wang, founder and president of the Center for China and Globalization, a Chinese think tank, at a recent conference in Beijing.

China, meanwhile, “has always been an active promotor of global governance ... and has embraced changes through openness,” he added.

More than words?

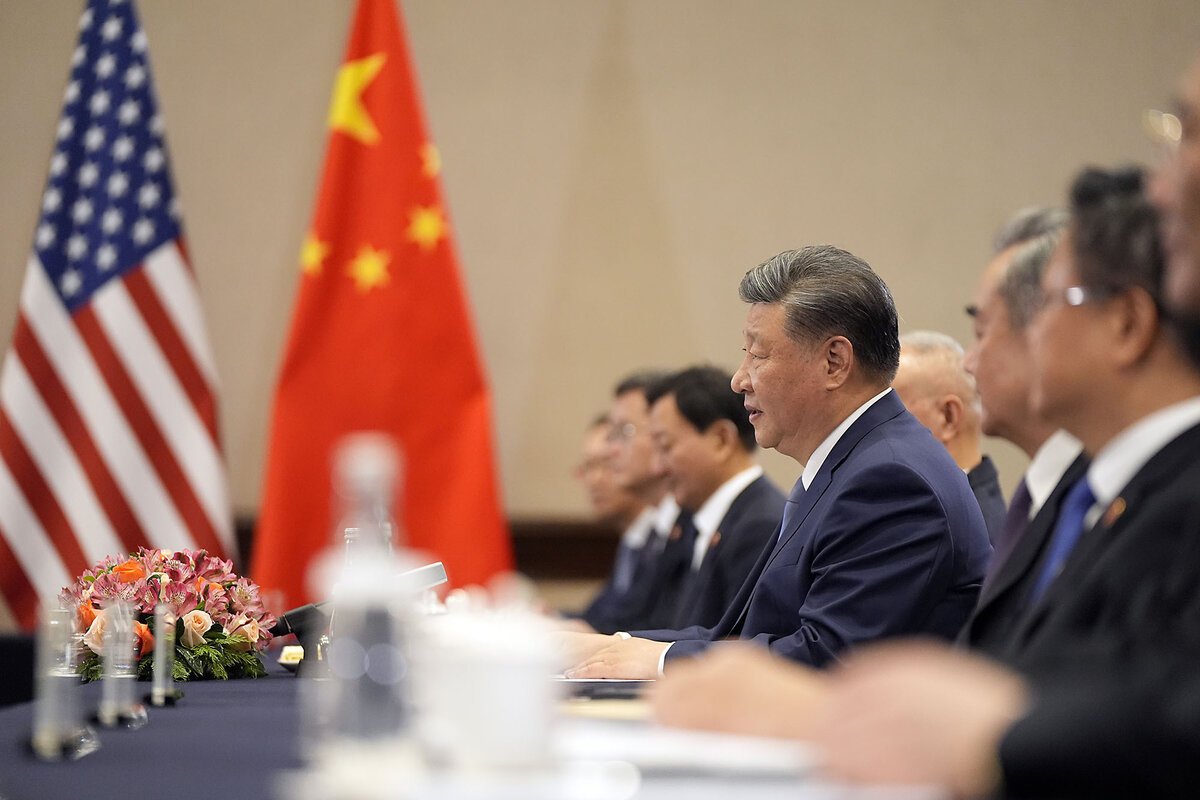

Indeed, as the U.S. election unfolded, Mr. Xi was already ramping up China’s diplomatic charm offensive, meeting with scores of heads of state over a few months last fall. He hosted the China-Africa summit in September. Then he attended meetings of BRICS in October, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation and the G20 in mid-November.

In December, China relaxed restrictions on visa-free travel, and launched a zero-tariff treatment for 43 of the world’s least developed countries. The latter is expected to boost China’s position as a global trading power.

Scott Kennedy, senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an American think tank, says that with Mr. Trump in office, “China might actually put more substance behind this outreach in terms of market access, industrial policy, security, and diplomatic issues,” and “see if they can peel away countries from their tight relations with the United States.”

If the Trump administration imposes tariffs and imposes more costs on its allies, it will aid China’s approach, he says.

Countries are well aware of the downsides of cooperation with China, including the risk of dependence and vulnerability to economic coercion, as well as the gaps between China’s rhetoric and reality. Overall, for example, the U.S. has lower tariff rates and fewer barriers to market entry than China does. The U.S. also welcomes more tourists and far more immigrants, and offers much greater protections for personal liberties, while China has a record of serious human rights violations.

“You can tell the story however you want ... but what people see are the facts on the ground,” says Dr. Economy. Nevertheless, she says the U.S. and its allies can often underestimate the traction of China’s message in the rest of the world.

“It’s possible,” she says,“that these ideas will resonate in ways that will surprise us.”