On rare visit, Xi Jinping tries to rescue China’s relationship with Europe

Loading...

| London

The visual contrast was striking: Spring sunshine bathed Paris when Chinese leader Xi Jinping last visited Europe five years ago. This week, he touched down for summit talks with President Emmanuel Macron under a cloak of gray cloud and drizzle.

But it’s the change in Europe’s political weather that will most concern China.

For years, amid its escalating trade battles with the United States, Beijing has been able to count on its other key Western trading partner, the 27-nation European Union, to steer clear of the superpower storm and keep economic relations on an even keel.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onFacing trade battles with Washington, Chinese leader Xi Jinping had hoped for a friendlier relationship with Europe. China’s subsidies for electric vehicle exports and its support for Russia’s Ukraine war have dashed those aspirations.

No longer.

A series of major jolts – the supply-chain effects of the pandemic, China’s repression of Uyghur Muslims, its crackdown in Hong Kong, and above all its support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – has hardened European attitudes toward Beijing among both the public and officials.

And a major new trade grievance, high on America’s agenda, too, is further straining ties: the huge volume of China’s state-subsidized exports of “future economy” products, including solar panels and electric vehicles.

With European producers finding it hard to compete, the EU is considering punitive tariffs.

And that has raised a deeply worrying prospect for China’s slowing, export-led economy: a two-front tariff war with both the United States and the European Union.

Mr. Xi will still hope to head that off.

The world’s second-largest economy has ample tools with which to retaliate, and a range of European industries would be vulnerable to such retaliation. Among them is the most important industry in the EU’s largest economy: Germany’s automobile sector.

An unmistakable chill has descended over China’s relations with Europe, and the political weather forecast does not look promising.

Mr. Xi began his European tour by calling on Mr. Macron, the West European leader with whom he has built up his strongest personal relationship. Mr. Macron has been an outspoken advocate of greater European “sovereignty” from Washington.

Still, he was also a prime mover behind the EU’s recent decision to open an investigation into – and potentially to sanction – China’s EV exports to Europe.

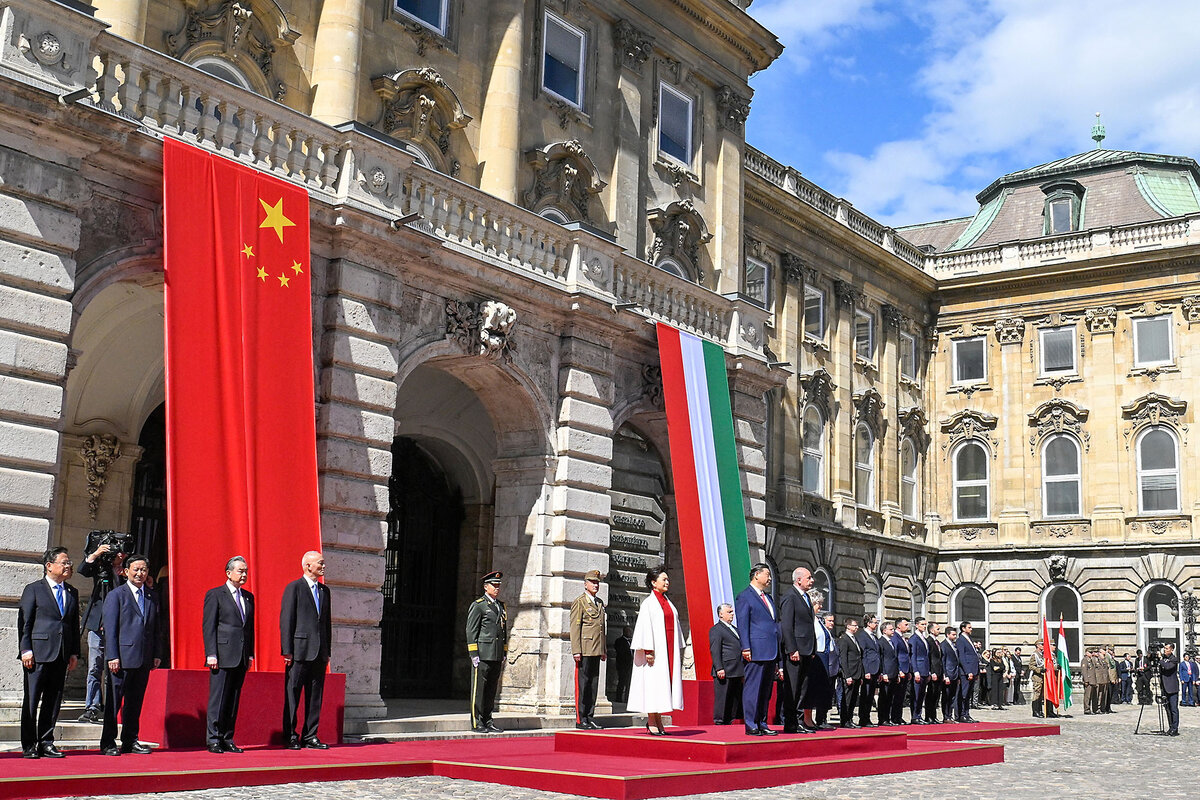

And Mr. Xi’s itinerary once he left France on Tuesday underscored the shrinking number of true friends he now has in Europe. He visited two East European countries: Hungary and Serbia. Both are expanding economic ties to Beijing. Politically, both support not just China, but Russia, too.

Five years ago, the atmosphere surrounding Mr. Xi’s European trip could not have been more different.

Yes, Europe shared many of the concerns that had prompted U.S. President Donald Trump to unsheathe the tariff sword and seek to reshape trade with China. Beijing’s limits to market access, its encroachment on intellectual property rights, its enormous state subsidies, and its export-heavy trade balance with the West – all angered Brussels as much as Washington.

But the EU still sought a negotiated resolution. It hugely valued its relationship with China, and wanted no part of the Trump-Xi standoff.

After leaving France five years ago, Mr. Xi traveled to Italy – which became the first G7 nation to sign on to China’s trillion-dollar global Belt and Road trade and infrastructure initiative.

And barely a year later, to the unconcealed frustration of the incoming Biden administration, the EU initialed a new comprehensive trade agreement with Beijing.

But EU ratification stalled, initially because of China’s retaliation against Europe’s criticism of its human rights record. Beijing’s recent support for Russia’s Ukraine invasion has left the deal not just on ice, but seemingly in permafrost.

In a further sign of the EU-China chill, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni pulled her country out of the Belt and Road structure late last year.

Mr. Xi’s talks with President Macron this week left little doubt that he wants to keep relations from deteriorating any further.

In the short term, that could mean trying to head off – or reduce – potential tariffs on China’s EVs by setting up plants in EU countries, something already planned for Hungary.

He could also try to revive the 2020 EU trade accord and use it to resolve other trade issues.

The main obstacle he has to navigate, however, has nothing to do with trade.

It’s the war in Ukraine.

Mr. Macron has long hoped to use his personal connection with the Chinese leader to persuade him to limit his support for Russia’s invasion, especially to curb exports of dual-use components that help Russia manufacture weapons. Ultimately, he wants Mr. Xi to intervene politically with the Kremlin and bring its war on Ukraine to a halt.

So far, at least, there’s been little sign of a shift. In fact, the Chinese leader is due to welcome Mr. Putin on a visit to Beijing next week.

Still, the French president seemed especially intent on strengthening personal bonds when the Macrons escorted Mr. Xi and his wife, Peng Liyuan, to the Pyrenees, where Mr. Macron used to spend childhood summers with his grandmother.

The excursion had all the makings of a feel-good crescendo to the visit: the majestic vista from a mountain pass perched more than 2,103 meters (6,900 feet) high.

But there, too, the meteorological omens augured ill. Thick fog hid the steep green valleys below.