Filipino journalists are often slain. This case is different.

Loading...

| Manila

It’s a case that would make headlines anywhere: On his way to the station, a popular radio host is shot dead by two motorcycle-riding assailants. A dramatic investigation ensues, implicating the country’s top prison official whose flashy lifestyle had been the subject of a recent radio segment.

But the fact that the wheels of justice appear to be turning for slain broadcast journalist Percival Mabasa, popularly known as Percy Lapid, is especially newsworthy considering how many journalists have been killed with impunity in the Philippines. The Committee to Protect Journalists ranks the Philippines seventh on a list of 11 countries with “the worst track record in solving murders of journalists during the past decade.” The country has been on the organization’s Global Impunity Index for 15 consecutive years.

Within a month of the Oct. 3 shooting, investigators homed in on Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) Chief Gerald Bantag, as well as deputy security officer Ricardo Zulueta and several inmates believed to be involved in the hit. Last week, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. urged relevant agencies to keep going “until we’re satisfied,” and the justice secretary dared Mr. Bantag to face his charges “like a man.” On Tuesday, the Department of Justice ordered subpoenas to be served to the suspects.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn a country where journalists are killed with impunity, the investigation into Percival Mabasa’s homicide is seeing progress. Can it offer lessons on seeking justice?

While friends and commentators say the speedy response is more of an anomaly than a budding trend, they do see reason for hope. So far, Mr. Mabasa’s case proves that when it behooves the government to solve a journalists’ homicide, authorities can make it happen.

“While we welcome the development in the case, we know for a fact it happened at a time that a new president is going out of his way to present himself as a leader who is committed to human rights,” says Carlos Conde, a senior researcher with the Asia division of Human Rights Watch. “If Marcos Jr. did not mention the case of Mabasa, it’ll be swept aside.”

Mr. Mabasa is one of three journalists killed since President Marcos assumed office in July. Radio broadcaster Rey Blanco was stabbed to death in Mabinay, a town in Negros Oriental province, on Sept. 18. Benharl Kahil, an editorial cartoonist, was shot dead in Lebak, in the southern Philippine province of Sultan Kudarat, on Nov. 5. Both cases are still under investigation and perpetrators are unidentified.

In addition to the timing, it also doesn’t hurt that Mr. Mabasa was a prominent, Manila-based journalist, says Jonathan de Santos, chairperson of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

“Most of the slain journalists were based in the provinces where there is barely government and media attention. Another probable reason why authorities have reacted quickly to this case is because Mabasa had many listeners and followings both on air and online,” he says.

“Culture of impunity”

At least 198 Filipino journalists have been killed since 1986, according to the NUJP, and judging by recent government figures, fewer than a third have reached a conviction.

“Most of the cases remain unsolved,” says Mr. De Santos. “The culture of impunity still prevails.”

And while some hope justice for Mr. Mabasa will deter future violence, media watchers are wary.

Jason Gutierrez, president of the Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines and a personal friend of the Mabasa family, says the fight for justice for Mr. Mabasa “is far from over.”

“His murder was just a tip of the iceberg,” he says. “It saddens me, but we must admit that this case has become a horrible proof that the country has many problems in its justice system and the web of corruption is a tangled mess.”

Gunman Joel Escorial surrendered to police several days after the shooting, and started naming co-conspirators. Shortly after, New Bilibid Prison inmate Cristito “Jun Villamor” Palaña, who allegedly acted as a middleman on behalf of the mastermind in Mr. Mabasa’s killing, died in detention.

An independent autopsy showed that he was suffocated with a plastic bag. Authorities have charged Mr. Bantag, the now-suspended BuCor chief, in both killings.

Fighting the chill

When journalists are killed with impunity, it can have a severe chilling effect on the press.

The fact that Mr. Mabasa was killed in Las Piñas City, on the outskirts of Manila, could make that self-censorship worse. Danny Arao, journalist and associate professor at the University of the Philippines, says the last time a journalist was killed in the capital was 2016.

“How many times have we seen some journalists in the provinces, where most of the media killings occurred, toned down in their reporting after a murder of a co-media worker?” says Mr. Arao. “A lot! ... The murder of [Mabasa] has shaken some media practitioners, not only community journalists but also those who are working in the mainstream media, in the capital region.”

Mr. Arao believes that it is the duty of the media to resist that feeling of intimidation.

“We should not let our young people who plan to enter the media industry fear engaging in investigative journalism and hard-hitting political commentaries,” he says. “We need to push back, harder and harder each day until justice is served.”

If there’s one positive takeaway from the Mabasa case, it’s that pushing back can work.

Many journalists say a key reason the national government mobilized its justice department and law enforcement to respond to Mr. Mabasa’s homicide was the reaction from the community.

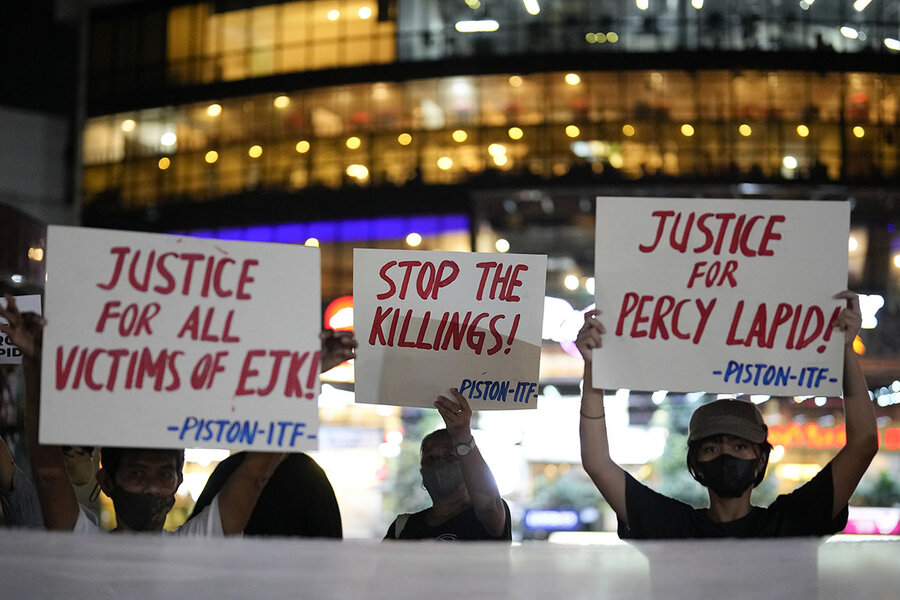

“Immediately after the news broke that Mabasa was killed, media workers, students, and human rights advocates rallied to denounce the murder and to put pressure on the government to hold the perpetrators accountable, because we know that press freedom is not complete if journalists are being killed,” says Mr. De Santos, a news editor at Philstar.com.

For Mr. Conde, the whole situation surrounding the Mabasa killing “could prove to be the impetus for the Philippine government to act on the safety and protection of media workers.”

“The challenge for Mr. Marcos Jr. is not only to stop the killings and human rights violations, but also to provide justice and accountability for those who were killed and whose rights have been violated,” he says.