Ravaged by meth, Australia's rural 'ice towns' get creative in fighting back

Loading...

| Wangaratta, Australia

At first sight, Wangaratta doesn’t seem like a place in the grip of a drug epidemic. Located on the main freeway connecting Melbourne and Sydney but far from the hubbub of either city, it’s typical of the modest country towns that dot Australia’s sparsely populated hinterland.

But in recent years, Wangaratta, an old gold rush town that exhibits a fading colonial charm, has gained an unenviable reputation. It has become known as an “ice town,” one of countless regional communities ravaged by crystal methamphetamine, or ice, of which Australians are among the world’s biggest consumers.

Since 2012, the highly addictive stimulant has fueled rising gang violence – including firebombings and the shooting of a local butcher – that had previously been unheard of in this town of 17,000 people. In 2014, drug-related charges more than tripled from the year before.

Now, Wangaratta is fighting back and, like many other regional communities with limited government support to draw on, townspeople are largely relying on themselves.

“Government funding is not the whole answer,” says Felicity Williams, a member of the Wangaratta Ice Action Steering Committee, which formed last year to coordinate the efforts of health, education, justice, and community agencies. “Many regional communities recognize that, and Wangaratta certainly recognizes that.”

'Whole-of-community' approach

Each month, the committee meets to share information and coordinate the work of the different bodies working to tackle the town’s drug problem.

“The data is really critical because we are trying to build a case … to put to government about what’s needed in this region and you can’t do it without evidence,” Ms. Williams says.

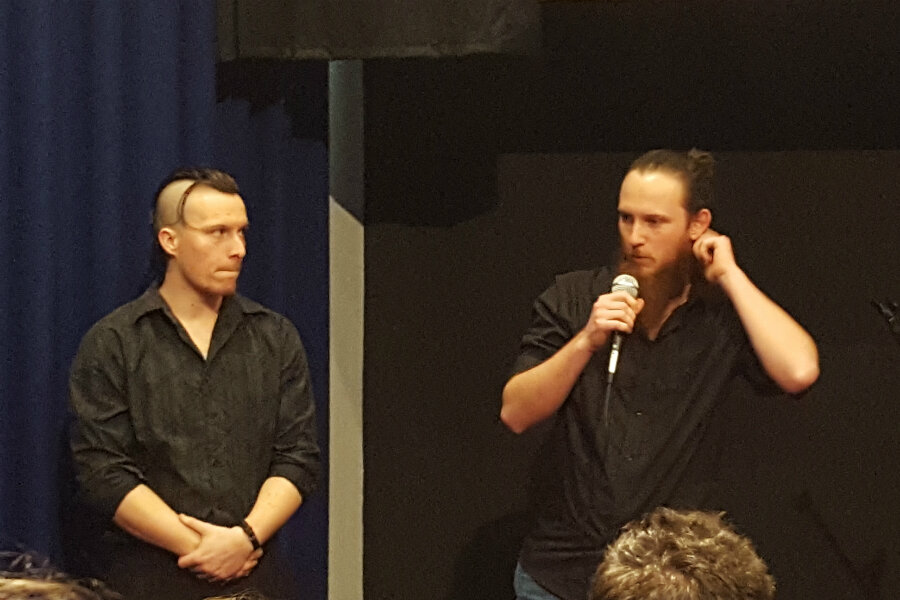

Educating people about meth and its dangers is a top priority. With the help of a state government grant, the committee recruited students from the town’s Centre for Continuing Education to produce “Slope,” a 45-minute dramatization of ice addiction, which will be screened at local schools.

“A story is more relatable,” says 18-year-old Alysha Tazzyman, who helped develop the screenplay along with two local filmmakers.

“If you have your parents going, ‘don’t do this, because I said so, because it’s bad for you,’ you are not going to understand,” says Ms. Tazzyman.

In the film, Josh, a young pub worker taking his first steps in adult life, finds himself led down the path of addiction by an older co-worker who fills the void left by the absence of his father.

Andrew Bowden, another committee member, speaks at sports clubs in the region about the risks of the drug, which has been linked to paranoia, hallucinations, and violent outbursts. He also explains what kind of help the authorities provide to those in thrall to the drug.

“I think it’s something, especially in a footy club, that players can relate to,” Mr. Bowden says, using the common name for the national sporting obsession, Australian Rules Football. “They’ll often know of someone who’s affected by it.”

Bowden believes that sport offers him a way to reach young people who might shut out the same information if they heard it from a teacher at school.

“It certainly raised awareness in the clubs, made people aware of what’s going on,” he says.

For families with a member in trouble with the law because of drug use, the anti-ice committee has put together a legal information pack, drawing on the experiences of the local family support group.

Williams, who is chief executive of the Centre for Continuing Education, says this “whole-of-community approach” is key. “There are multiple issues with lots of complexities,” she says.

While residents still complain of inadequate services, such as a lack of detox facilities, the state has offered at least some recognition of their initiative. Last year, Victoria unveiled a $370,000 grant plan to fund grassroots efforts in towns like Wangaratta.

Nationally, the government has made the empowerment of local citizens a key plank of its four-year, $300 million ice-reduction strategy, allocating almost $25 million in funding to community groups.

“Government alone can’t tackle this issue, and we’ll be working with local communities on the ground,” said Fiona Nash, then minister for Rural Health, when the federal government announced its plans.

Rural areas hit hard

Wangaratta’s ordeal is not uncommon; small towns right across Australia have found themselves facing similar problems. One study last year found that more than twice as many ice users lived in rural areas as cities. Far from the teeming coastal metropolises, jobs are often hard to find, leading to the boredom and despair that can feed initial interest in the drug.

In Wangaratta’s surrounding environs, more than 21 percent of young people are jobless. Life is draining out of towns like Wellington, dubbed “Little Antarctica” because of its ice problem, as people move away to bigger cities.

“There’s nothing to do, unless you have your [driving] license and disposable income,” says Tazzyman of the boredom that drives many young people to the drug.

With a gram of ice selling for $500, an intense high costs about $50. Dealers offer poor people credit to lure them into drug use.

“You can’t do that going out for dinner,” says Tazzyman.

Just a year into the community’s push to rehabilitate their town, it’s too early to say that Wangaratta has turned the corner. But there have been promising signs. Drug offenses fell by more than 30 percent last year, although overall crime ticked up slightly.

Above all, the committee is adamant that people’s awareness is growing, opening up discussion and lessening the stigma that lingers around drug use in a small community where word travels fast.

“There’s a stigma that prevents people from accessing services,” Williams says. “It’s a matter of coming forward and getting that support.”