How Pentagon leak suspect’s violent words escaped notice

Loading...

| Washington

In March 2018, a high school junior in North Dighton, Massachusetts, was suspended after a classmate allegedly heard him discussing guns, Molotov cocktails, and racist threats.

To those who knew him online, this wouldn’t have been a surprise. The student – Jack Teixeira – was a gun-loving, edgy teenage gamer. The servers he frequented in the years to come included members who were obsessed with the military and posted Nazi memes.

But that didn’t prevent Mr. Teixeira, the next year, from getting an IT job with the Massachusetts Air National Guard. Neither, in 2021, did it stop him from getting a Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information clearance – the highest level the government awards.

Why We Wrote This

There are 2.8 million people with U.S. security clearances. Some of them exhibit online behavior that should disqualify them from access to secrets – and intelligence agencies are studying better ways of identifying those people.

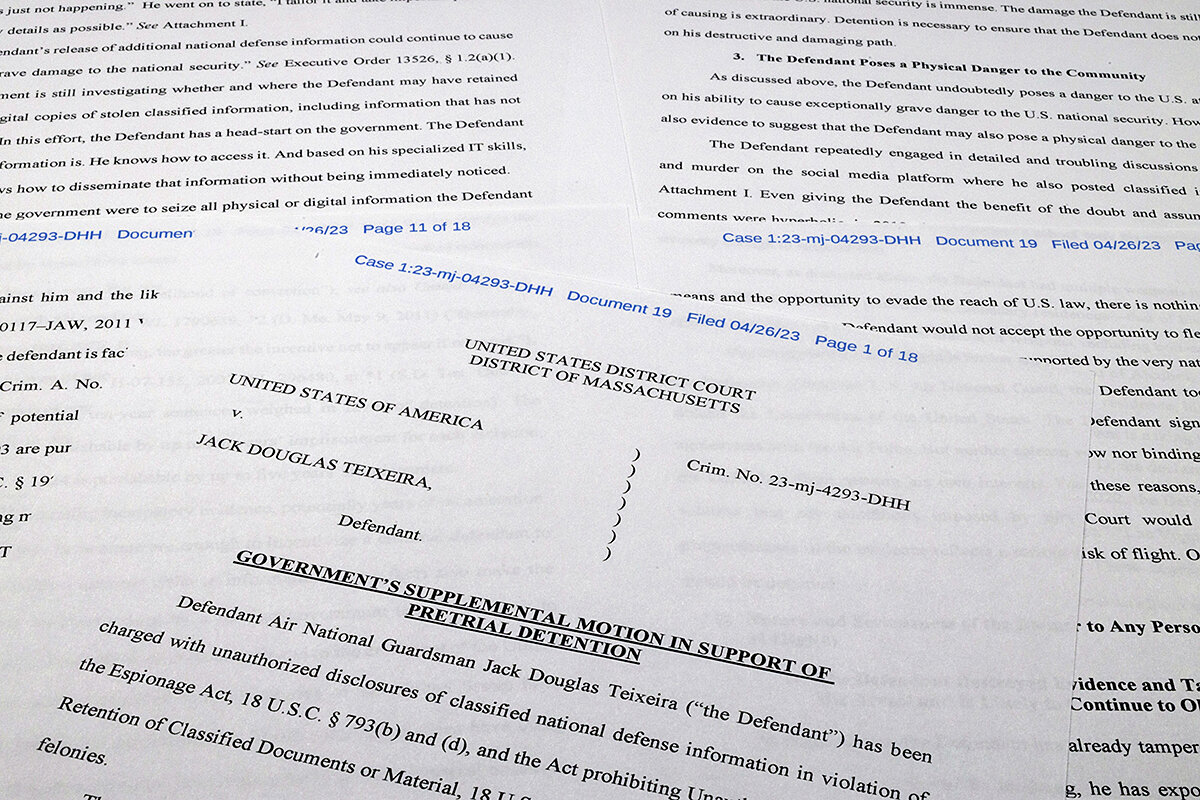

Now Mr. Teixeira stands accused of abusing his position, and then some. Last month, he was arrested and charged with being the perpetrator of the largest leak of U.S. intelligence in a decade. Since last October, he has allegedly posted hundreds of highly classified national security documents on Discord, a popular gaming site.

The Discord leaks have presented a list of questions for the American intelligence community – about how someone in such a niche outfit could have access to some of the nation’s most furtive secrets and why the leak took so long to spot. But as more details of Mr. Teixeira’s past come out, former intelligence officials are also starting to wonder how he got a clearance at all – and how he even made it into the military.

“It seems like they didn’t do a very good job vetting him at the very outset, to say nothing of when they were considering his security clearance,” says Evelyn Farkas, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for Russia, Ukraine, and Eurasia. “It’s a total failure.”

It’s a failure, former officials argue, that may say less about Mr. Teixeira than the system he worked for. The American intelligence community is a sprawling bureaucratic neighborhood of agencies and levels of classification. In 2017, the number of people with active Top Secret security clearances was just under 1.2 million – including government employees and contractors, and officials at all levels of seniority. Even as the Pentagon investigates this leak and tries to contain its damage, there are simply too many people with top clearances across too many levels of government to audit them all.

Gaming culture

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine last February, Mr. Teixeira reportedly began posting classified information about the war to an online Discord chat room of 600 people. He would continue doing so for months, but in October began concentrating on another online group, a community of 50 mostly young gamers on a Discord server called Thug Shaker Central.

There, reportedly as the group’s leader, Mr. Teixeira posted transcripts and then photos of highly classified documents detailing U.S. intelligence secrets from the war in Ukraine to arms supply in South Korea.

Besides boasting classified documents in its chat, Thug Shaker Central was a portrait of online gaming’s often lewd, offensive culture. According to a Department of Justice filing last week, Mr. Teixeira “had regular discussions about violence and murder on the social media platform.” Last November, according to a Department of Justice filing, he stated that “if he had his way, he would ‘kill a [expletive] ton of people’ because it would be ‘culling the weak minded.’”

When the FBI raided Mr. Teixeira’s family home in Massachusetts on April 13, according to the same filing, they found a gun safe containing bolt-action rifles, an AK-style weapon, and a gas mask 2 feet from his bed.

This is not the profile of someone the United States wants with a top-secret clearance.

“It’s exposing something that’s quite systemic,” says Amy Jeffress, a former Department of Justice prosecutor and national security lawyer. “We keep seeing these cases where individuals who really should not have access to our most highly classified information do have access to it.”

Part of the problem, Ms. Jeffress argues, is that the government classifies too much information – it’s just seen as a safer option. But a high volume of classified documents demands a large number of government employees with security clearances: around 2.8 million in total as of 2017.

Another issue is that top secret information is shared widely among different parts of the intelligence community, a choice that dates back 20 years, when a lack of intelligence sharing was faulted, in part, for the government’s failure to anticipate the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The upside is that sharing intelligence helps avoid catastrophe. The downside is that more widely shared intelligence is harder to keep secret.

“Every intelligence crisis has an aphorism or a saying that comes out of it. After 9/11, it was ‘information sharing, connect the dots,’” says Michael Allen, who worked in President George W. Bush’s National Security Council. “But now we’ve clearly overshared the information.”

Secret PowerPoints

The documents Mr. Teixeira posted on Discord were J2 briefing slides, the highest-level intelligence product America’s intelligence community creates every day, says former Defense Intelligence Agency and National Security Council official Javed Ali.

Those slides – essentially a daily PowerPoint presentation for the nation’s top policymakers – are posted to an online bulletin board of sorts known as the Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communication System, or JWICS (pronounced “jay-wiks”). For Mr. Teixeira, it was as simple as accessing JWICS, printing out the slides, and taking them home.

Members of the intelligence community work on keyboards that track their every keystroke and printers that log their every print. But those tools better suit an audit than a real-time alarm, says Mr. Ali. Thousands of people access JWICS each day, he says.

Mr. Teixeira was an IT employee, which made his clearance kind of like the head electrician at the White House, says Dr. Farkas, now director of the McCain Institute, a Washington-based think tank. He needed a clearance in case he saw something secret at work. But he had no “need to know’’ such sensitive information.

The intelligence community needs a better way to enforce that need-to-know standard, she says. The Department of Defense is working on a yearslong project to make its computer networks “zero trust,” which would mean users need to continuously authenticate their credentials before accessing information at different levels. But that structure likely wouldn’t have prevented all of Mr. Teixeira’s leaks, and is still years away.

“How do you begin to regulate a system that’s compartmented like crazy with all these different levels of classification?” says Mr. Allen.

Mr. Ali recommends added scrutiny of social media accounts and airport-level security at secure sites, maybe even random bag checks. But even those protocols, he concedes, aren’t perfect. Even members of the intelligence community have constitutional rights to privacy.

“These are things that are hard to do,” says Mr. Allen. “But ... any system that doesn’t detect some of these red flags is, by definition, flawed.”