Will Pentagon leak sour US relationship with its allies?

Loading...

| BERLIN and SEATTLE

When the leak of classified Pentagon documents came to public light last week, the controversy was as much about who they informed on as what details they contained.

While some of the material in the papers focuses on American geopolitical rivals like Russia, such as the magnitude of its losses in its invasion of Ukraine, other portions of the trove detail information about key U.S. allies like South Korea, Israel, and Ukraine.

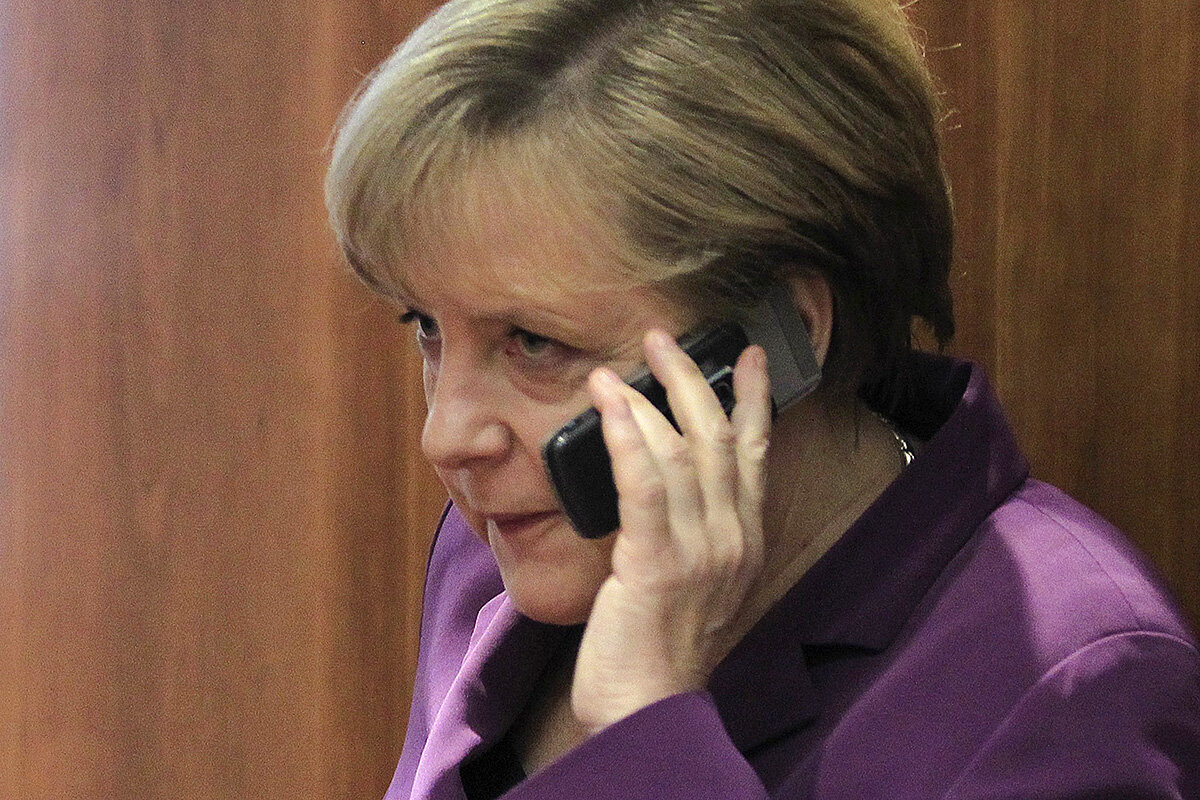

It is not the first time U.S. intelligence has been caught spying on its partners. Just a decade ago, a WikiLeaks report showed extensive American hacking of phones in Europe, including that of Angela Merkel, infuriating and embarrassing the German chancellor.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe Pentagon leak has put sharp focus on both the strength of U.S. alliances and the fragility of relationships that need constant tending – especially in an era of disinformation.

But the leak poses a pair of challenges for U.S. allies. First, it raises questions about just how secure the much-vaunted U.S. intelligence system – which many American allies rely on – really is. And second, it threatens the solidarity of democratic governments as they attempt to hold together against autocratic and nationalist forces during a testing historical period – one all the more challenging due to the largest land war since World War II.

“There’s a greater cause at the moment which makes this sort of intelligence breach less dramatic than past breaches,” says Liana Fix, a fellow for Europe at the Council on Foreign Relations, “and that’s the context of the war.”

“A pretty inconvenient moment”

Trust in American intelligence and in relationships with the United States was enjoying highs following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Donald Trump’s departure from the White House.

The number of Germans viewing the U.S. relationship in a positive way quadrupled in the last two years to 82% according to Pew Research, with a roughly equal proportion of Americans feeling similarly about the U.S.-German relationship. The same goes for U.S. allies in Asia: An early 2022 poll found that 87% of South Koreans believe their country should have closer ties to the U.S. than to any other nation.

Positive public sentiment in such countries toward the U.S. should help buffer the news that America has been an imperfect partner when it comes to protecting secrets. It’s also not news that allies spy on each other.

“It’s fairly established that mutual spying is done rather regularly on many levels,” says Ian Lesser, executive director of German-Marshall Fund’s Brussels office. “But it always holds the potential to create enormous policy challenges for governments because there is this disconnect between insider official perceptions on the issue and its effect on public opinion.”

In 2013, for example, the Edward Snowden leaks revealed that the National Security Agency had been listening in on Chancellor Merkel and other top German and European officials. That revelation prompted Germany to call in the U.S. ambassador and seek out an apology and reassurances that such activity wouldn’t continue, while Ms. Merkel proclaimed, “We need to have trust in our allies and partners, and this trust must now be established once again.”

The Five Eyes alliance of the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom have agreed they won’t spy on each other, but otherwise there’s no accepted international standard on the activity.

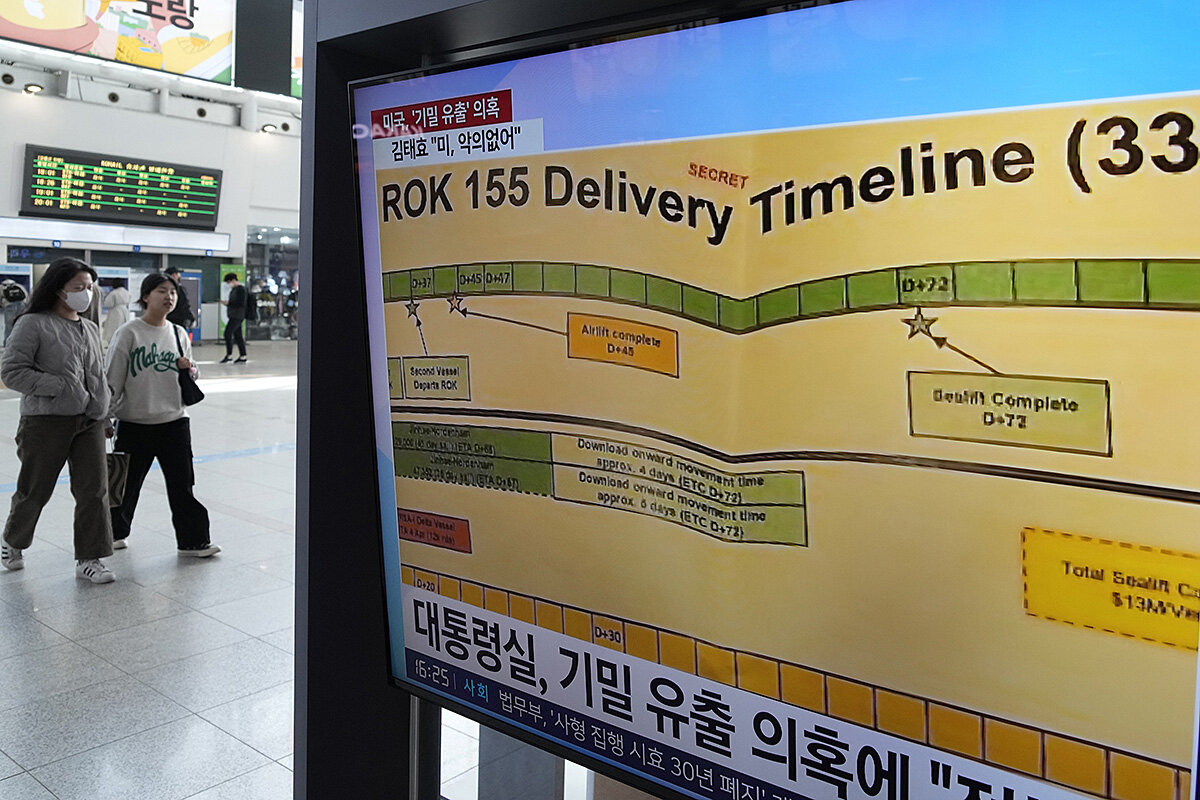

This time around, one of Washington’s most important allies in Asia – South Korea – was thrust into an awkward spotlight by the leaked Pentagon documents.

The documents allegedly disclosed concerns voiced by senior South Korean national security officials that by providing artillery shells to the U.S. – if diverted to Ukraine – South Korea could violate policies that bar it from providing lethal munitions to countries engaged in conflicts.

The revelations stirred controversy as South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol is scheduled to make a state visit to Washington on April 26, including a White House dinner hosted by President Joe Biden, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the U.S.-Republic of Korea alliance.

“Obviously it comes at a pretty inconvenient moment,” says Daniel Sneider, an expert on U.S.-ROK ties and lecturer in East Asian Studies at Stanford University. Opposition politicians are using the incident to attack Mr. Yoon as being obsequious toward the Americans, he says. “The Yoon administration and the Biden administration, they’re doing their best to carry out damage control.”

Yet aside from needing to manage public opinion, experts say they see little harm from the leaked information itself to the alliance with South Korea. “The content of what was discussed in itself has very little intel value,” says retired South Korean Army Lt. Gen. In-Bum Chun, former deputy Chief of Staff of the ROK/U.S. Combined Forces Command. The policy discussions over Seoul possibly providing weapons to a war zone were an open secret, he and other experts said.

Endangering individuals, revealing sources

But there will be acute concern that the U.S. is unable to protect its sources, as the details of what was leaked could reveal identities of people who share information with the Pentagon.

Such sources could be hauled before their governments and made to answer for their actions. In countries like Egypt – which according to the documents was pondering supplying weapons to Russia – sources may disappear, says James Davis, professor of international politics at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland.

“That creates a bigger problem, as it does make it more difficult for individuals to cooperate with our intelligence services,” says Dr. Davis.

This information also reveals operational interests in an ongoing war. “What does it tell adversaries about how we gather information? That’s always the real concern – it’s not just the information itself but who’s gathering it, who’s helping, and who’s not helping,” says Dr. Lesser of the German Marshall Fund.

The leaks also make reference to “LAPIS time-series video,” a satellite-based imaging technology that could now be more susceptible to interference from Russians.

Outrage will be tempered

In the end, the U.S. and its allies will continue to share intelligence, defense experts predict.

After all, information sharing is sorely needed among allies at this critical time, and U.S. intelligence in particular has proven valuable. In February 2022, Germany was blindsided by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s armies marching into Ukraine, with the head of the German foreign intelligence service famously needing to be evacuated overland by special forces when Ukraine’s airspace was shut down. “He didn’t expect the war to actually break out on that day,” says Dr. Fix, the Council on Foreign Relations fellow.

In other instances, terrorist cells planning attacks in Germany have been identified by U.S. intelligence. “The allies benefit enormously from America’s intelligence capability and that tempers any outrage and leads to a more balanced response when these things come out,” says Dr. Davis, the international politics expert.

Meanwhile, South Korea is a crucial strategic and economic ally of the United States in Asia. The two countries have a mutual defense treaty, and some 28,500 U.S. troops are based in South Korea. In 2022, South Korea was the United States’ seventh-largest trading partner.

“The manifold security challenges ... actually call for strengthening, not cutting back on, intelligence-sharing” between the allies, says Rachel Minyoung Lee, senior analyst for the Open Nuclear Network in Vienna and a former North Korea analyst for the U.S. government.

“For the Yoon administration, a strong U.S.-South Korea alliance forms the cornerstone of its foreign policy. Keen to expand and strengthen U.S. extended deterrence, ... it will try to minimize fallout from this incident.”

Ultimately, it is clear there are “massive numbers” of both classified documents and people with clearances. “The system as a whole has to be rethought,” says Dr. Davis.

“If we were only classifying the really secret stuff and making sure the people who had access to the really secret stuff were trustworthy, we’d probably have far fewer events.”