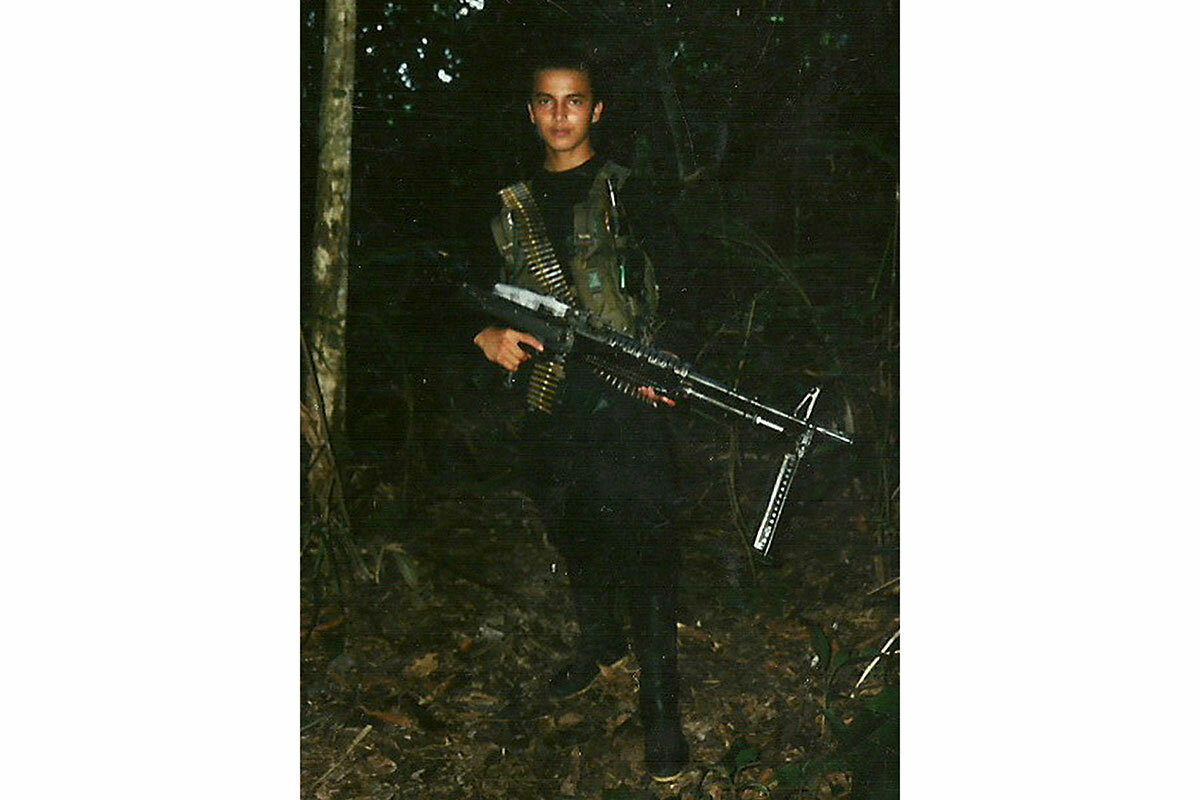

‘I’m shooting images instead of people.’ A former guerrilla changes his lens.

Loading...

| San Isidro, Colombia

Ferley Vargas might be standing on his former comrades’ graves, but he can’t remember well.

What he does remember is the viscous sensation on his feet a few days after the fight in this green, hilly tract, when he had to carry an injured fellow fighter on his shoulder. Her blood trickled down his uniform and filled his rubber boots. “That kind of thing is hard to wash away,” he says.

Today, Mr. Vargas is also wearing rubber boots, but he holds a camera, not a gun. A TV cameraman, he’s one of more than 10,000 demobilized rebels from FARC, also known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, which signed a landmark peace accord with Colombia’s government in 2016.

Why We Wrote This

Last week by video, Colombian guerrillas declared war against the government once again. But Ferley Vargas, both a victim and perpetrator of violence in the past, won't be joining them.

“I’m shooting images instead of people,” he says.

When Mr. Vargas goes back to his childhood village, old acquaintances come to shake his hand; others congratulate him for leaving the FARC and making a go of civilian life.

More than 400 miles south of Bogotá, the road to the tiny strip of houses in Caquetá department is muddy and luminous at the same time, just like Colombia’s path to peace.

Last week, a former top FARC commander known as Iván Márquez issued a new call to arms in a video, accusing the government of failing to uphold the 2016 peace agreement. Alongside him was Jesús Santrich, a former FARC leader and lawmaker who is wanted by the United States for alleged conspiracy to export 10 tons of cocaine.

In total, as many as 3,000 dissident fighters, scattered in small groups, are estimated to be resisting the deal, according to Insight Crime, an organization that tracks organized crime. Mr. Márquez is now trying to unite these factions and work with other guerrillas. President Iván Duque’s government has vowed to track down and capture the rebels in the video, while expressing support for the rehabilitation of former FARC members.

The country has long been divided over ex-combatants’ role in society. Critics of the 2016 peace deal say it was too soft on the guerrillas, granting them 10 seats in parliament. Its defenders argued that it was not a total amnesty, and that the agreement struck a necessary balance between peace and justice.

Weapons down, a first step

Despite this polarization, most people agree that surrendering weapons was just the beginning of a long journey to building a lasting peace in Colombia. After more than five decades of conflict that left 200,000 dead and displaced 6 million people, it can sometimes seem that this country of 49 million has never known anything else.

That was the case for Mr. Vargas. “I didn’t even know that this was conflict. I had to go out of the war to figure out that I was part of it,” he says, his voice rising above the sound of his car wheels spinning in the mud. “But if I did it, the country can do it too.”

Even before “vanishing into the jungle,” he says violence was a normal part of life. When he was 5, his dad died in his mother’s arms in their kitchen. The family fled their home several times with only the clothes on their backs. At age 13, he witnessed his mother being dragged by soldiers from their home to take her to prison, accused of collaboration with the FARC.

Soon after, Mr. Vargas joined the guerrillas. For four years he carried a picture of his father in a coffin. It was his only personal item. The promise he wrote on the back reads, the person “who did that to you will die by my hands. I’m going to take revenge for you so you can rest in peace.”

“I was never a revolutionary. I liked the war the way a child looks for protection,” he says, walking toward the cemetery where his former comrades are buried. Passing a one-story house with closed wooden doors painted in black and a sign that says “Disco,” he stops to shoot a short video with his personal camera: “This is the house where my dad was killed.”

Nearly 3,700 children, 1 in 5 under the age of 15, joined FARC between 1999 and 2016, according to Colombia’s child welfare agency. International humanitarian law forbids the recruitment of soldiers under 15.

It’s hard to know their motives precisely. A 2012 United Nations study of Colombian child fighters suggests that many joined because they believed an armed group would offer them an income, food, or security.

Seeking a way to farm without coca

Leaving FARC behind forced Mr. Vargas to find another way to survive. In Caquetá, the region where the 28-year-old now lives, that is easier said than done. Many farmers in the area still rely on coca for cash income to supplement their subsistence crops.

In San Isidro, three men share a milkshake at a small bakery, before joining a meeting next door with 25 other farmers. The meeting is about converting their coca fields to other crops, and it’s the reason why Mr. Vargas is there. Top of the agenda is the muddy road to town.

“Transportation of goods is the main obstacle for substitution here. What do you want them to grow if they can’t sell anything?” says Balvino Hurtado Polo, a local leader, when Mr. Vargas turns on his camera.

The only visible government presence in San Isidro is a handful of soldiers, who are not here to fix the road but to support a national coca substitution plan.

Colombian government officials insist that peace is only possible if coca growers in former FARC regions like Caquetá convert their crops. “There is a direct relationship between the drug trade and violence,” says Emilio Archila, a presidential counselor for stabilization and consolidation who runs the substitution program.

The program has yet to show results. Since the 2016 peace accord, Colombian coca planting has increased, with a small drop in 2018 to 208,000 hectares, according to the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy.

One man’s transition to peace

At the beginning of 2007, Mr. Vargas learned that a member of the FARC was responsible for his father’s execution. His father was accused of being an Army informant; Mr. Vargas says this was untrue.

He deserted the guerrillas soon after, intending to join an anti-FARC paramilitary group. His contact in the paramilitary turned him over to the Colombian police, where he feared he would be shot dead when they officers asked him to surrender. They spent 15 days debriefing him about the guerrillas. Mr. Vargas lied about his age so he could go through the demobilization program faster. But an administrator found out he was still a minor, and he was transferred to a foster home in Bogotá.

The conversion to civilian life was hard: It took him five years to find his purpose. He went back to school and became one of the few demobilized combatants to pursue higher education. He now works for one of Colombia’s largest broadcasters.

“Most of my childhood friends who joined the FARC didn’t have the chance to go out of it,” he says.

Expressing himself helped reverse his emotional numbness, as he found his voice again. And slowly, he has restored his faith in humanity. As the truck roars over the mud, he looks out at a landscape that holds dark memories. “It’s like I can still hear the bullets sometimes. But now I know right from wrong,” he says.