How a global crusade is working to save the improbable reef of Cartagena

Loading...

| Cartagena, Colombia

Luis David Lizcano-Sandoval is looking for just the right spot to descend. With his hand-held GPS unit at the ready, the marine biologist from the University of Valle in Cali, Colombia, issues instructions to our boat’s driver, Pablo: a la izquierda, to the left, or a la derecha, to the right. Just a few hundred yards from us, loaded container ships pass to and from Cartagena, Colombia’s main port city. Each time one chugs by, our tiny boat rocks energetically in its wake.

Mr. Lizcano-Sandoval signals to Pablo to cut the motor, then jumps into the water and disappears. A few moments later, his head pops back up. “This is it,” he says. Together, we don our masks, let the air out of our scuba vests, and start sinking beneath the waves.

The first few feet of water are what you’d expect in one of Latin America’s busiest harbors – nothing but a yellow-tinted haze, a layer of polluted sediment that rises to the surface like oil. But about 10 feet down, the pea soup abruptly turns clear and turquoise.

Why We Wrote This

The first time Valeria Pizarro dived in Cartagena Bay, she was expecting to find a few small corals, and little more. Instead, she found one of the world's most unusual reefs, an underwater "rainforest" that sparked a local dispute – and scientists’ curiosity around the globe.

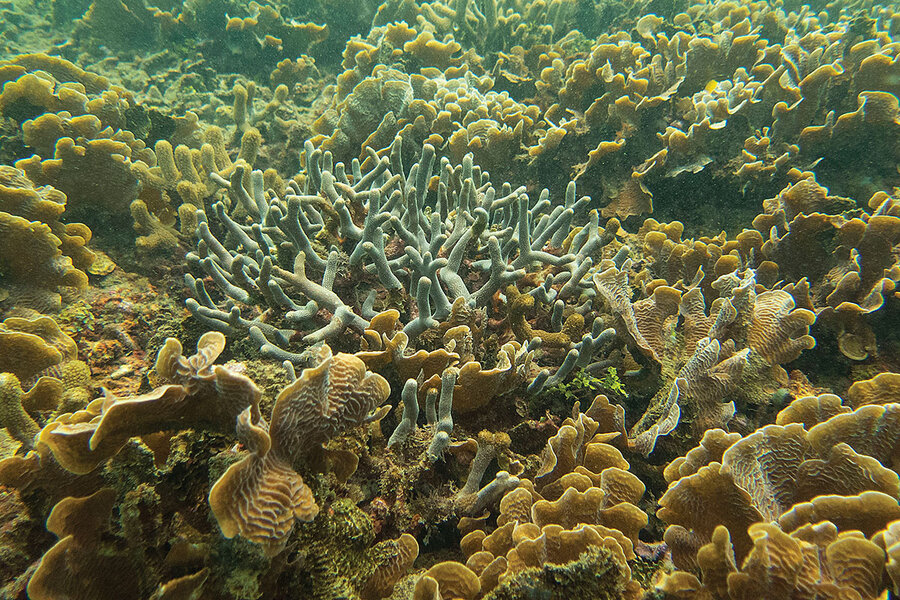

As a cool ocean current drifts through, a massive vista opens up to reveal something that, by all scientific logic, shouldn’t be here – a kaleidoscopic reef garden, rising out of the depths like some fanciful rampart. Over on one edge, there’s a purple coral behemoth with convex shelves jutting out. Darting surgeonfish flank orange coral domes, each one as wide as an outstretched arm. Bright sea fans dot the landscape, waiting to extend their tendrils for the floating plankton that sustain them.

“It’s like a city,” Lizcano-Sandoval says as we surface, spitting salt water. This arresting time-capsule world, he thinks, may look much the same now as it did centuries ago, when Spanish conquerors built fortress walls around Cartagena to keep marauding pirates out.

For the coastal communities that have harvested its bounty for centuries, and for the scientists who officially discovered it five years ago, there is no reef like Varadero. Locals call it “the improbable reef,” and for good reason: It has persevered in the midst of intensive coastal development, streams of toxic runoff from the nearby Canal del Dique (Dike Canal), and waters so warm they’d turn many reefs into lifeless skeletons. Scientists like Lizcano-Sandoval and Pennsylvania State University’s Mónica Medina are working to uncover the secrets of Varadero’s striking resilience – secrets they can use to help other threatened reefs around the world.

But just as Varadero begins to yield its tantalizing scientific bounty, it’s looking as if the reef may be damaged or even destroyed. A group of government officials, port authorities, and businesspeople is planning to dredge a channel so Cartagena’s harbor can accommodate more container ships – a move they say will boost the nation’s economy. However, the researchers who study Varadero, along with local environmental activists, are hoping to stall the dredging project so the reef’s storied legacy can continue – and perhaps contribute to the rescue of other endangered underwater Edens.

***

Coral reefs like Varadero are the rainforests of the oceans: diverse ecosystems that contain more species per square mile than almost anywhere else on Earth. Even though reefs cover only about 1 percent of the world’s seabeds, they contain at least one-quarter of all sea life. Smithsonian Institution researchers now think the biodiversity of reefs might be even higher than previously thought: When they surveyed a variety of coral reefs, 38 percent of species they came across were rare ones (found only once), and 81 percent of species were found only in a confined local area.

Millions of people around the world, especially in coastal zones, depend on coral reefs for their bounty of fish. Reefs also protect vulnerable coastlines from storm surges and attract tourists interested in snorkeling and diving.

But a variety of human-caused phenomena, including gradual sea warming, pollution, and ocean acidification from dissolved carbon dioxide, are pushing many coral reefs to the edge of extinction. When ocean temperatures rise too high, the tiny coral animals that make up reefs expel their zooxanthellae, “helper algae” that use photosynthesis to make food for the corals. As a result, the corals turn white or “bleached,” and having lost their main food source often die soon thereafter. And when too much carbon dioxide from tailpipe emissions saturates ocean waters, the higher acid content that results can damage reef structures, causing them to crumble. Not only does that threaten corals, it endangers the marine species that depend on reef formations for shelter.

As factors like these have converged in recent years, the pace of reef destruction has picked up. A 2017 study by UNESCO found that 25 of the world’s most important reefs, which make up about three-quarters of the world’s reef systems, had undergone significant bleaching in the past three years. One, the Great Barrier Reef, lost about 30 percent of its coral cover in 2016 alone. Other mass die-offs have decimated systems from the Caribbean to the Indian Ocean.

The need for solutions has never been more urgent, and marine scientists are scrambling to come up with ways to save the world’s underwater rainforests. The Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota, Fla., for instance, is growing corals in controlled conditions that researchers will later transplant onto faltering reefs. Mote aims to plant more than a million corals to replace dead or dying ones.

Another promising avenue involves creating “coral probiotics”: supplying threatened corals with a mixture of bacteria from healthier corals, which may make their systems more resilient to stresses such as warming waters and disease.

These strategies have yet to be tested on a global scale. But in the absence of such drastic measures, coral reefs as we know them could virtually cease to exist by 2100, which is one reason activists are focusing so urgently on what lies at the bottom of the bay here.

***

The project Valeria Pizarro took on in January 2013 seemed like an innocuous one. A Colombian marine biologist and an experienced diver, Dr. Pizarro carried out underwater environmental surveys for a variety of clients. This time, a consulting agency representing Cartagena’s port developers had hired her to check out a location near the mouth of Cartagena Bay.

Cartagena was growing and flourishing as never before, and developers wanted to dredge the location to create a new shipping lane for large boats. A previous survey had reported that the bottom of the bay was largely devoid of life. A “degraded reef,” the survey called it. Pizarro’s job would be to find whatever small clusters of coral still remained. She would then transplant these stragglers elsewhere to clear the way for the new shipping lane.

Pizarro’s goal for her first dive was simply to survey the area before going back for more detailed analyses. As she descended through the murky water, she braced herself for the degraded reef she’d been told to expect. Maybe I’ll find some small corals, she thought. Maybe some medium ones.

Then, in less time than it took to exhale a lungful of bubbles, the vista changed. An entire unspoiled coral reef, in made-for-IMAX colors, unfurled like something Gabriel García Márquez had dreamed up. Pizarro paused, trying to take in the magnitude of it all. One question lodged in her mind: How come? This reef, she knew, should not exist. Its presence was a feat of magical realism.

One of the men who’d hired Pizarro was on the boat with her when she discovered the reef. “We have a problem,” she said to him after she surfaced.

“What is it?”

“We don’t have a few colonies here. We have a coral reef.”

The consultant balked, telling Pizarro they probably weren’t in the right spot. But she stuck to the evidence she had seen through her mask.

Over the following weeks, Pizarro methodically surveyed the entire area. There were thriving reef formations everywhere, fortresses of coral extending all across the bay’s mouth. “We dove the whole [thing], trying to find the best place for the shipping channel,” Pizarro says. “We never found that place.”

It wasn’t long before she decided she had to get out of the project entirely. She knew it might mean taking a financial hit, but she couldn’t stand the thought of helping to destroy the undersea world she had just uncovered.

***

It took some time for Pizarro, now executive director of Colombia’s ECOMARES foundation, to process the discovery she’d made. But the response from her fellow scientists was a good gauge of its magnitude. Researchers started calling Varadero “the heroic reef” – a nod to Cartagena itself, dubbed “the heroic city” after surviving centuries of sieges and attacks.

The year after Pizarro found the reef, Mateo López-Victoria, a biologist at Pontifical Xavierian University in Cali, Colombia, rushed a short journal article into print to tell the world of the reef’s existence. The dispatch sketched out Varadero’s unique qualities in broad strokes.

“The largest colonies found must have survived repeated human disturbances,” Dr. López-Victoria and his colleagues wrote. “This coral formation is a unique resource that should be conserved and further studied considering its high species diversity, the large size of some of its coral colonies, and the atypical conditions under which it developed.”

Thanks to the initial surveys they’ve done, researchers have gleaned some insights into what makes Varadero unique. “Corals in Varadero have a very distinct growth pattern,” says biologist Roberto Iglesias-Prieto, Dr. Medina’s colleague at Pennsylvania State University. Specifically, the corals grow about twice as fast as similar corals elsewhere, but their skeletons are less dense; it’s possible that these traits give them an advantage over their slower-

growing coral counterparts.

Medina thinks certain elements in runoff from the Canal del Dique may be benefiting the corals in surprising ways. “Part of the day, [the corals] get these nutrient-rich waters where they’re eating and photosynthesizing,” Medina says. She notes that fairly recent changes in coral growth coincide with a period when more sediment was being dumped into the bay.

It’s likely, then, that certain reefs actually thrive on some nutrients found in canal runoff. Varadero’s corals might also benefit from their location right at the mouth of Cartagena Bay. “They have constant communication with the sea,” Pizarro says. The fresh inflow of ocean water might lessen the impact of toxic mercury, cadmium, and copper that runs off into the bay from nearby industrial facilities.

Medina and her colleagues are trying to figure out if other aspects of the reef’s biology contribute to its success – aspects that could ultimately be replicated in reefs elsewhere. “There is something about the location,” Medina says. “Everybody does better in Varadero.” Samples of microbes from Varadero’s corals – the onboard collection of bacteria, viruses, and algae that perform critical metabolic tasks – have revealed that they are totally distinct from those found on other reefs, Medina says. Her lab is conducting a detailed analysis to find out whether the microbes might be performing important functions, such as fighting disease, that help the corals to survive even in less-than-ideal conditions.

In the future, if conservationists can transport Varadero’s hardy corals to other endangered reefs around the world, or even seed threatened reefs with whatever microbial cocktail helps Varadero’s corals thrive, those reefs might have a better chance of surviving despite ocean warming and pollution. Many of the world’s reefs now hang in a liminal zone between death and survival. By putting Varadero corals’ survival tactics to work on other threatened reefs, scientists like Medina, Lizcano-Sandoval, and Pizarro hope to tilt those reefs a little bit closer to the side of life.

***

The big question hanging over these investigations is whether the scientists will be able to finish them at all. Developers’ dredging plans stopped after Pizarro first discovered the reef, but Colombia’s Ministry of Transport, Cartagena port authorities, and developers have since come up with a revised dredging proposal. While the new plan is designed to be less damaging to Varadero than the initial one, it would still involve slicing a shipping channel across the heart of the reef.

Officials at National Development Finance (FDN), which funds national development ventures, are backing the dredging plan because of the economic opportunity they say it offers the region. As one of the 10 largest ports in Latin America, Cartagena handles more than 2 million containers per year, and dozens of ships enter the bay each week. FDN says the channel project would boost Colombia’s competitiveness by reducing boat traffic delays and allowing ships to reach Cartagena more easily.

“Currently, Cartagena’s port has a unique navigation channel way, which increases the ships’ waiting time for entry and exit from the harbor,” says FDN spokeswoman Juliana Maria Restrepo Marin. If plans for the new channel go forward, she adds, more ships will be able to reach the port, which would create more jobs and reduce the cost of some consumer goods. “This new project will have economic benefits, not only for Cartagena, but for the whole country.”

Pizarro estimates, however, that the latest planned dredging operation would ruin at least a quarter of the reef, a blow that would threaten much of the remainder. That’s why a group of Colombian activists, including psychologist and teacher Bladimir Basabe, is working to make sure dredging plans never come to fruition. At a conservation conference Mr. Basabe attended a couple of years ago, one presenter talked about Varadero, and Basabe – who had never heard of the reef at the time – was entranced. For many years, the consensus had been that “the bay does not harbor any coral, that everything is dead,” he says. “The corals of Varadero have shown the opposite, to society and to world science.”

When Basabe found out the reef might not survive the decade, he resolved to act, forming a nonprofit called Salvemos Varadero (Save Varadero). Other local activists, including environmental lawyer Rafael Vergara – a former Colombian M-19 revolutionary – soon joined the cause. Ideally, Basabe says, “what will happen is that the channel project will be totally suspended, and the project area will be forced to change.”

After Salvemos Varadero was created, its leaders swung into action in a 21st-century way: They posted a petition on change.org, describing the reef and urging people to resist the planned dredging operation. More than 25,000 people have signed the petition so far. “The defense of the reef is a victory,” Mr. Vergara says over coffee and Oreos at his seaside Cartagena apartment. He scoffs at developers’ projections of economic growth, saying the city wouldn’t necessarily see increased shipping traffic after dredging operations – and that even if it did, the project would still be a mistake. “The corals,” he says, “are more important than the gains of private companies.”

***

The dredging project is currently under environmental review, and the developers have pledged to abide by the results of the review, whatever they might be. “We want to be clear that the project will only take place if it’s environmentally viable, and if it has all the legal and environmental authorizations,” Ms. Restrepo Marin says.

To get approval to proceed, the developers will have to update their environmental license from Colombia’s National Authority of Environmental Licenses. In order to secure license renewal, project partners will consult with communities from the area surrounding Varadero, communities that benefit directly from the reef’s bounty of fish. “The communities are becoming more informed. They have united with activists,” Medina says.

Many locals have a detailed understanding of what they stand to lose if the reef disappears, which may make it harder for developers to make the case for dredging. Colombia’s National Natural Parks authority and activists from Salvemos Varadero are also involved in the discussions about the reef.

At the very least, Pizarro says, the meetings between different parties will take several months, which should stall dredging approval long enough for Colombian citizens and others around the world to learn more about the reef. The ideal outcome of the discussions, in Pizarro’s view, would be for the country’s Ministry of Environment to add Varadero to an existing marine protected area that surrounds the Rosario and San Bernardo archipelagos. “That will be just what we need,” she says. “It would be the ultimate goal.”

In principle, Colombia’s National Natural Parks authority favors this goal. “We are ready to support the creation of permanent spaces that guarantee the protection of these corals,” says Luz Elvira Angarita, Colombia’s National Natural Parks director of the Caribbean territory. Right now, she says, the main obstacle is that Colombia’s current environmental budget does not cover the extra cost of adding Varadero to the protected area. But since national legislators reevaluate this budget from year to year, activists could potentially persuade them to allot more money to keep Varadero intact.

Basabe is also pushing to get the reef added to Colombia’s official coral reef atlas, which is maintained by INVEMAR, the country’s institute for marine and coastal research. The atlas hasn’t been updated for years, and since Varadero does not appear in its pages it is not entitled to the same environmental protections as reefs that do.

From her light-filled upper-floor apartment facing Colombia’s Santa Marta mountains, Pizarro ponders the reef’s future. As the scientist who discovered Varadero, she feels as bonded to the reef’s inhabitants as she does to blood relatives. “I have lots of pictures of coral,” she says, laughing, as she scrolls through her laptop’s photo gallery. “Corals are part of my family.”

While she’s optimistic about Varadero’s prospects, she knows the economic pull to expand Cartagena harbor is strong. “For me it’s, ‘This reef is unique.’ For them it’s, ‘We need it for development,’ ” she says. “Yes, you’re going to get a few million dollars. But in the long term, this reef is going to give us lots more.”

This spring, oceanographer Sylvia Earle’s international Mission Blue alliance named Varadero Reef an official Hope Spot, a distinction that activists say strengthens their case. Vergara, for one, is confident, refusing to even consider the prospect of losing the reef. “We have to win,” he says, with echoes of his old revolutionary fervor.

If officials and citizens agree, the “heroic reef” can continue to teem with life – and scientists like Medina can go on cracking the code of its resilience. “All we want,” Vergara says, “is permanence.”