From inside a Ugandan camp, one refugee helps others tell their stories

Loading...

| BIDI BIDI, UGANDA

Growing up in southern Sudan, James Malish often stayed up late into the night, listening to his mother tell folktales by the fire. At school the next day, he would recount the stories to his enthralled classmates, adding his own dramatic flair.

Back then, he saw stories as pure entertainment, a kind of spoken word soap opera to pass the time, and a way for him to be close to his mother and friends.

“I never thought that storytelling had the power [of] helping your community,” he says.

But as civil war tore apart that idyllic life, forcing Mr. Malish and his family to flee to Congo, and later Uganda, telling stories took on a new significance for him. It became a lifeline to the place his family had lost, and a way for people in the community of refugees where he lived to shape how the world saw them. Since May 2019, he has run a Facebook page called “Daily Refugee’s Stories,” a Humans of New York-like platform that shares snippets of the refugee experience in Bidi Bidi, one of the world’s largest refugee settlements.

The stories and photos that accompany them are personal and intimate – a young artist working on a portrait, a group of children roasting sweet potatoes, a gospel musician preparing for a concert.

They bring life in Bidi Bidi – a sprawling settlement of more than a quarter million people near the border with South Sudan – down to a human scale. On Daily Refugee’s Stories, Mr. Malish says, big-picture issues faced by refugees like hunger, lack of clean water, or poor education get personalized treatment, which he and the site’s other contributors hope makes them more relatable and accessible.

It also hands the microphone directly to a group of people who often have their stories told for them by others, says Moses Acole, a community development specialist at the Italian NGO Associazione Centro Aiuti Volontari (ACAV), which works with refugees in Bidi Bidi. “The mainstream media … tends to dictate the terms on what to cover about refugees, who have no choice” in what stories are written, he says.

Mr. Malish’s project started by chance. It was 2018, two years after he’d fled South Sudan for the second time in his life, in the midst of brewing civil war. He saw an advertisement pinned on a notice board at Bidi Bidi, advertising a World Food Program-sponsored course to teach digital storytelling tools to refugees in the settlement. At the time, Mr. Malish was volunteering at a clinic in the settlement, and on a whim, decided to apply.

“I wanted to do something different,” Mr. Malish remembers thinking, “And to do that, I had to apply for this opportunity because I didn’t want to go back [to South Sudan] one day as the same person I was before.”

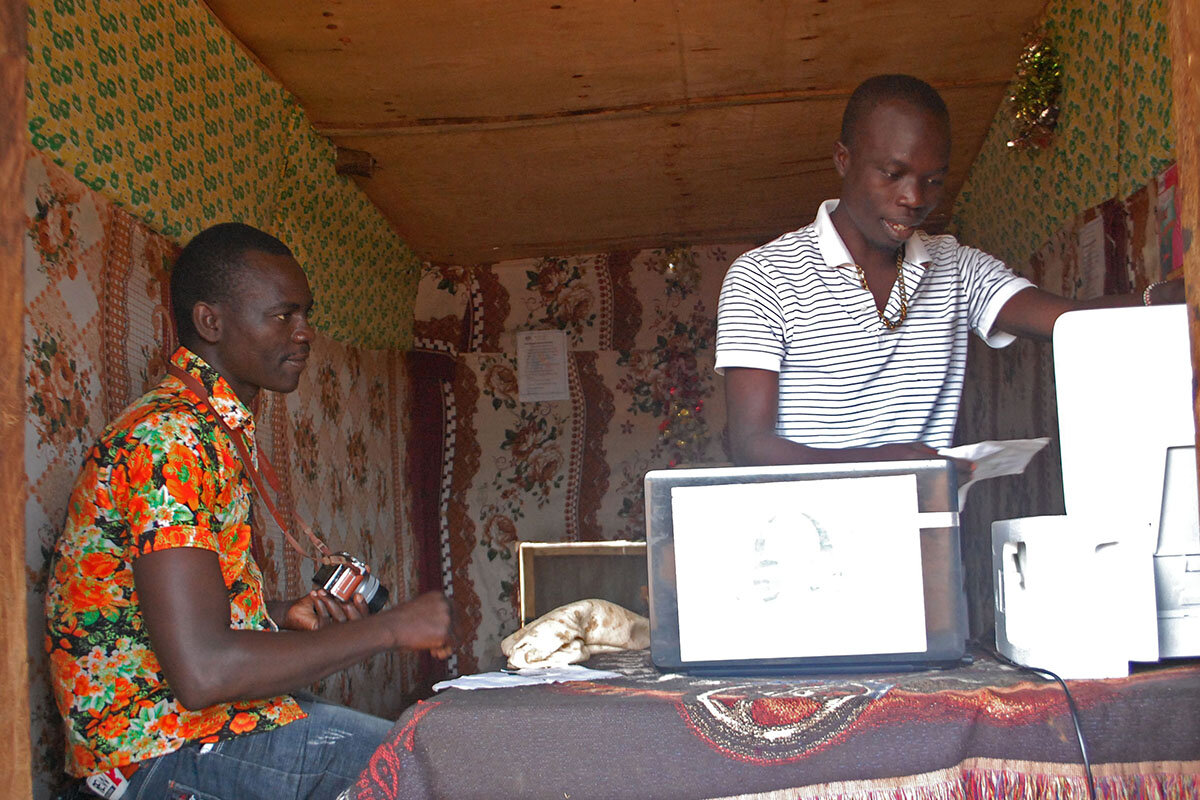

During the two-week training, Mr. Malish learned about photography, videography, and writing for social media audiences. At the end of the program, he was given a smartphone, and began to post stories and photos on the program’s Facebook group, Bidi Bidi Storytellers.

Soon, Mr. Malish’s posts began to attract outside attention. A BBC crew traveled to Bidi Bidi to film with Mr. Malish, and he decided to create his own, spinoff Facebook page, Daily Refugee’s Stories.

The page quickly gained traction. When Mr. Malish wrote about how a drastic cut in food rations had affected the elderly and single mothers, readers in the United States and South Sudanese in the diaspora came forward with donations. Later, two nongovernmental organizations fixed 10 broken taps and boreholes after Mr. Malish’s page alerted them to the problem.

Rosebell Kagumire, a media specialist who was one of Mr. Malish’s trainers in the WFP course, says when refugees tell their own stories, they are able to “humanize their whole … experience.” This, she adds, helps in “bridging those gaps with the host communities who often fail to understand their needs.”

When Mr. Malish saw how well received his Facebook page was among South Sudanese in the diaspora, he decided to expand and started a small NGO called Afri-Youth Network, which teaches business, tech, and art skills to young people in Bidi Bidi.

“We want to give them a purpose – something they can learn so that they are able to make good out of themselves,” he says.

So far, Mr. Malish has trained about 30 young people in the same kinds of digital storytelling skills he himself was taught three years ago. His course is a month long, and teaches video, still photography, and script writing.

Last year, he was invited by the World Economic Forum to give an online talk about the issues faced by refugees. To him, he says “this was a sign that my work is being recognized as I continue to be the voice of the people in my community.”

Charles Thomas, who came from South Sudan in 2016 and was trained in the storytelling course, says the program helped “because I want to be the voice for the people in the community where I understand their issues since I am part of them.” Mr. Thomas, who dreams of becoming a journalist one day, currently contributes to Daily Refugee’s Stories.

Tonny Charles, who fled from South Sudan in 2017, says that since he completed Afri-Youth’s storytelling program, he has written multiple movie scripts and also acted in feature-length films that he and his program peers film on their smartphones using skills they learned in the program.

“I love storytelling. When I act in film or drama, it makes me a better person after I have freedom to be a different person and live their lives,” says Mr. Charles. “Besides that, most of the subjects [are] social problems that youths face and [the films] are aimed at educating them.”

To Mr. Malish, who lives at Bidi Bidi with his wife and four children, this is just the start. He plans to roll out the program to all refugee settlements in Uganda, just as soon as he can find the money. In the meantime, he has been looking for new ways to tell the stories of South Sudanese refugees in Uganda to the world.

“Many people don’t understand what conflict feels like. They have just watched it in a movie,” he wrote in an op-ed for The Independent in June. “Refugees are people who have really experienced it. You leave your country. You run for asylum. … But, with support, you can also land on your feet. I’m a living testimony to that.”