‘Numbers don’t lie’: The team ‘Counting Dead Women’ in Kenya

Loading...

For years, whenever Kathomi Gatwiri complained that violence against women in her home country of Kenya was out of control, she got used to hearing the same response: prove it.

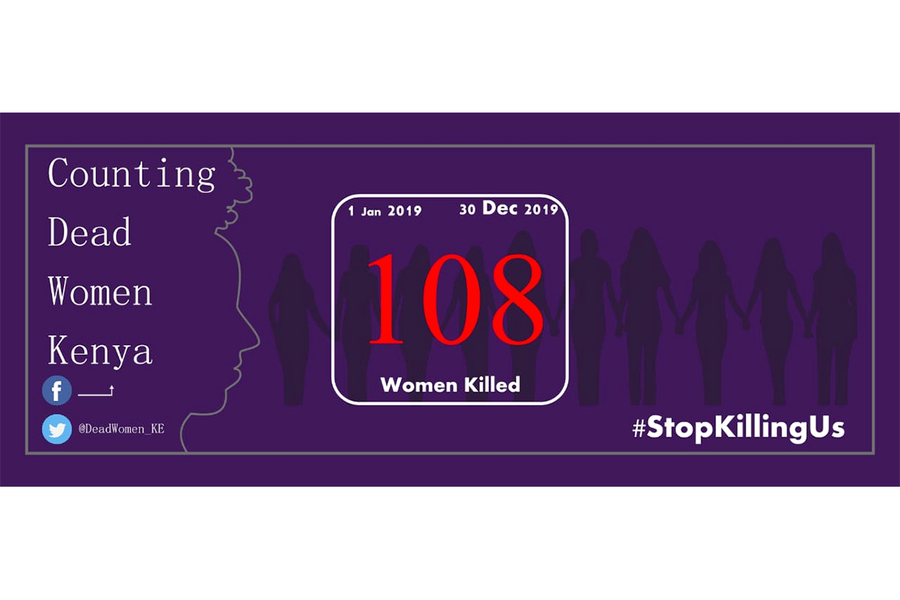

So at the beginning of 2019, the academic and one of her best friends from college, Audrey Mugeni, decided they would do exactly that. They set up Facebook and Twitter pages called “Counting Dead Woman – Kenya” and dedicated themselves to a grim project: creating an online archive.

Since then, the pair have dutifully recorded every woman’s murder that has been reported in Kenyan media.

Why We Wrote This

They say defining the problem is half the solution. Sometimes, that starts with something as simple – but powerful – as counting the problem. Women’s advocates are publicly tallying victims of femicide as a step toward change.

Lucy, set on fire by her husband for returning home late.

Eunice, a university lecturer stabbed to death in her car.

Helen, killed by her boyfriend for alleged infidelity.

By the end of December, the number of victims in their database had risen above 100.

“This data is important because numbers don’t lie,” Dr. Gatwiri says. “When we talk about women issues we’re often accused of being emotional and not relying on facts and figures. But these are numbers – and faces and stories – that you cannot argue with.”

Their project joins a growing number of movements worldwide dedicated to documenting the murders of women, in hopes that spotlighting the extent of the problem will hold those in power accountable for reducing crimes that often go unpunished.

“It’s not a perfect method, but at least it’s a starting point for tracking what’s going on,” says Sibusiso Mkwananzi, an associate lecturer in demography and population studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. “You can’t interrogate the questions of why this keeps happening until you collect and study the data.”

In North America, there is Women Count USA and the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women database. France has Féminicide. And both the United Kingdom and Australia also have local Counting Dead Women pages.

In every case, the projects say they are filling gaps in the data around women’s violent deaths around the world. In the United States, Australia, and Kenya, for instance, there is no complete national database of women killed by men, a crime often referred to as femicide. But rarely do these projects stop at the numbers. Counting Dead Women – Kenya, for instance, posts whatever information it can find about the victim and her murder.

“What we are asking for is to put a story to these women so we don’t forget them,” Dr. Gatwiri says. “This was a woman with a name and a family and people who loved her, who is no longer with their community because of a violent act.”

Diana and Stevan, 9 years old and 4 years old, raped and murdered inside their house.

Valerie, 16, killed by a classmate whose advances she had rejected.

Esther, a land rights activist whose body was dumped on a farm near her house.

Dr. Gatwiri and Ms. Mugeni say they scour major newspapers for reports and increasingly collect tips from the project’s supporters. They have no inside information on police investigations or trials. And looking at statistics on domestic violence – which an estimated 40% of Kenyan women experience in their lifetime, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics – they know their data barely scratches the surface.

“We know there are so many stories we will never hear this way,” Dr. Gatwiri says. But they hope their data, however limited, will hammer home how widespread the problem is and inspire the government to collect more complete information.

And projects like this also help tell a new story about violence against women, says Shakila Singh, an associate professor and gender-based violence expert at the University of KwaZulu Natal in South Africa.

“These stories remove the illusion that the danger against women comes from strangers in public places,” she says. “In fact, we see that for women the home is not a safe place. The family is not a safe place. It demystifies some of the ideas we have about who kills women, and who they are not safe around.”

Indeed, in many parts of the world, including sub-Saharan Africa, women are more likely to be killed by their intimate partners than by a stranger. Sixty-nine percent of murders of African women are committed by a family member or romantic partner, a higher rate than any other region in the world. That statistic is accompanied by persistent victim-blaming, Dr. Gatwiri says: Why did she dress that way? Why did she lead him on?

Ivy, a medical student hacked to death by a man she turned down.

Fenny, shot by her police officer husband after a fight.

Carolyne, her throat slit by her boyfriend after a night out.

Already, Dr. Gatwiri says Counting Dead Women’s statistics are being regularly used by the Kenyan media and advocacy groups to bolster articles about the extent of violence against women in the country. Next, she hopes they will begin tracking what happens after a woman is murdered – is her killer brought to trial? Convicted?

“We know they often disappear into obscurity without facing justice. Why?” she says.

But the project is also a shoestring operation, run largely by Dr. Gatwiri and Ms. Mugeni, both of whom have other, full-time work. Dr. Gatwiri is a senior lecturer teaching social work and social policy at Southern Cross University in Australia, where she has lived for the past eight years, and Ms. Mugeni is a master’s student in gender studies in Nairobi.

“We don’t want to keep doing this – it’s a horrible job to count women like yourself who are being murdered every day,” Dr. Gatwiri says. “The fact that we have normalized the killing of 94 women this year alone [as of early December 2019], the fact that it hasn’t jolted us into action yet, the fact that we are still debating if these women deserved to be murdered tells us a lot about the values we espouse as a country.”

At the same time, however, she sees the violence as a symptom of wider social crises.

“We have rising levels of unemployment, we have widespread feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness. We have a society that has taught men that the only acceptable emotion is anger,” she says. “If we want to fix this problem, we also have to talk about the whole structure of our society that enables it to happen.”