Reporter's Notebook: On edge of Sahara, camel is what's for dinner

Loading...

| Agadez, Niger

Discerning taste buds in the West may be unfamiliar with camel meat. Perhaps what gives pause is the thought of converting ornery camels – the working end of long, grimy caravans that have crossed deserts for centuries – into delicacies of the table.

But that hasn’t stopped chef Abdoulaye Mahamane from dishing up his signature camel dish with peanut and spinach sauce. And from the kitchen of the boutique Auberge d’Azel hotel – a tiny, last bastion of civilization in Agadez, Niger, on the southern frontier of the sweltering Sahara Desert – he says there is one group of guests who can’t get enough.

“It’s mostly Americans who always eat the camel,” says Mr. Mahamane, the head of the kitchen, whose clients range from a University of Chicago crew of dinosaur hunters – in Agadez en route to launching a two-month desert expedition – to European Union military advisers, who passed through recently.

Why We Wrote This

Reporters do get to out-of-the way places. Eating local foods can challenge not only their taste buds but their very concept of what counts as food. The adventure can be rewarding.

In recent days guests also included a pair of foreign journalists on the trail of a world-wide human migration story, both devout foodies and one of them an American, who of course ordered the camel. Twice.

Mahamane’s camel stew has an earthy flavor, enhanced by ground peanuts and shriveled spinach greens, and cooked to tender perfection with cumin, ginger, and saffron. It’s served on a bed of couscous.

The result is, for lack of a better word, delicious – creating a pronounced cognitive dissonance with the conjured images of this famously bad-tempered curmudgeon of a pack animal, its meat turned leathern by years of constantly battling its owner-friend – and surviving in the harshest of environments.

“The Americans all want it,” says Mahamane, shaking his head in surprise. “I don’t know why.”

Even in these parts, where the temperature routinely tops a stultifying 105 degrees Fahrenheit, eating camel can be a controversial practice – akin to the reservations some in the West have about eating meat from domesticated animals they once formed bonds with when living, such as dogs, cats, and horses.

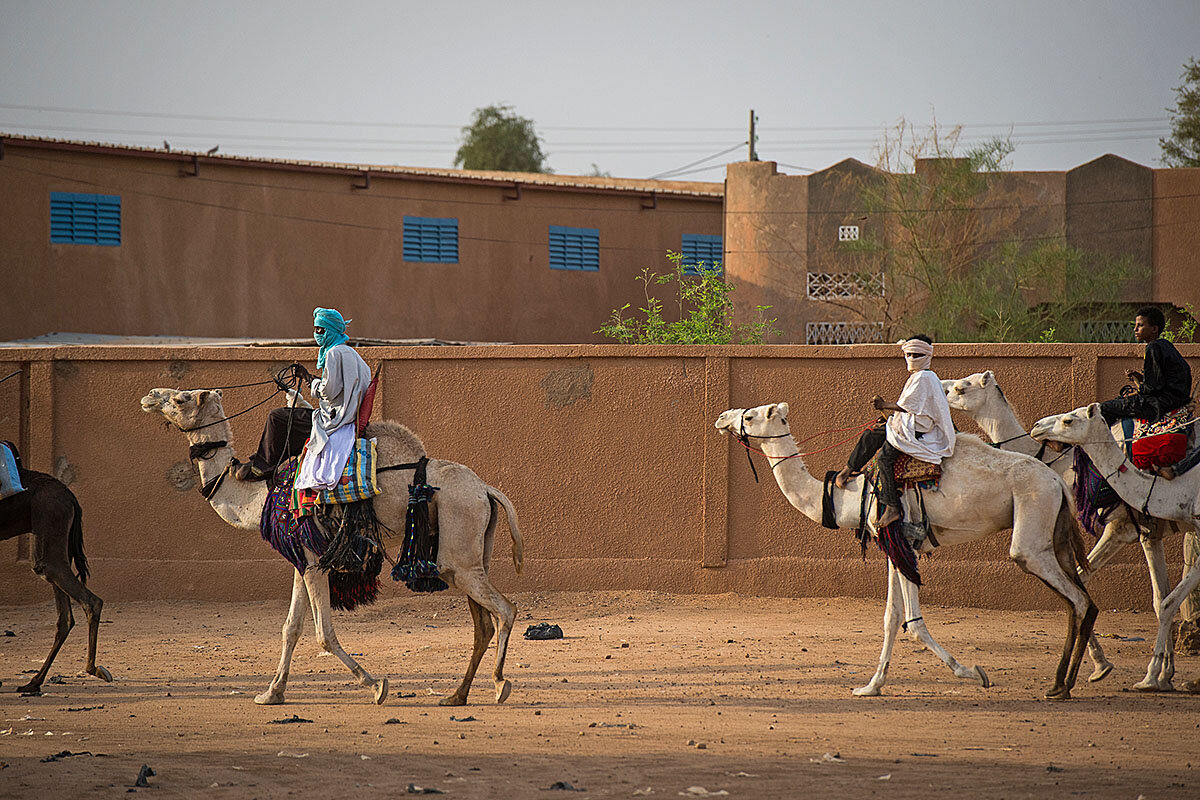

With their soft snout thick with long bristly hair – just don’t get near the powerful teeth and tongue, which bite hard and can easily tear through thorn tree branches – and very long eyelashes designed to protect their eyes from blowing sand, camels have defined cultures of nomadic tribes from the western Sahara across Africa toward Somalia and Yemen and beyond.

“It’s an important animal for us, we have a special relationship,” says Mahamane, who describes the rituals involving camels of his nomadic Tuareg tribe of northern Niger and the Sahel. They have depended upon the long-legged, loping beasts to sustain life in such a hostile environment since camels were first domesticated by humans some 5,000 years ago.

“As Tuaregs, we rely on camels to carry us into the mountains and into the bush,” he says. During marriage ceremonies, there are often camel races, as well as a fantasia ritual, in which people stand in the middle and sing, while camels circle.

Some Tuaregs – such as Minat Alhou, who is himself a carnivore – believe that camel meat is imbued with medicinal powers of healing when “no other medicine will work.”

But not all will visit the butcher where thick hunks of camel meat are sold for $2.39 per pound, about 40 cents cheaper than beef.

“There are some Tuaregs who eat camel, and others who won’t, even if they like meat,” explains Mahamane. “Those who don’t eat it ask, ‘How can you eat the animal that works for you?’ ”

But cooking camel requires care, so that the dish doesn’t wind up as indigestible as the hardscrabble existence from which spring both camels and nomadic tribes.

“Camel meat is tough!” exclaims the chef, who warns against under or overcooking. He recommends making stew dishes from the haunch, where the mix of meat and fat is at its flavorful best.

Among the other cuts that are sold are camel tongue, filet, and organ meats. Ribs are cut up to make sauces.

But beware the age of the meat you are buying, warns Mahamane. The cost of young and old camel meat is the same. Optimal age for tenderness is two years old. But with camels living an average of 40 or 50 years, there are plenty of jaw-grinders in the market.

Mahamane, who is in his mid-20s, runs his kitchen with practiced mastery, and he learned the camel dish – his only one so far – during a three-month apprenticeship with a chef from the small West African state of Benin, where, ironically, camels are scarce.

He then studied under a Tuareg chef for a year, where he learned to create other specialties on the menu, including Tuareg-style mutton stew (slow-cooked with cumin), and spicy mutton tagines richly flavored with sauces of dried fruit or homemade pickled lemon.

Mahamane says he is considering new possibilities, especially as demand is high – especially among Americans – to eat these ships of the desert.

“As time goes by, I can imagine wanting to learn another camel recipe,” he says.