Letter from South Africa: What Melania could have seen

Loading...

| Johannesburg, South Africa

As first lady Melania Trump zig-zagged across Africa last week, the trip, at first, seemed largely without fanfare.

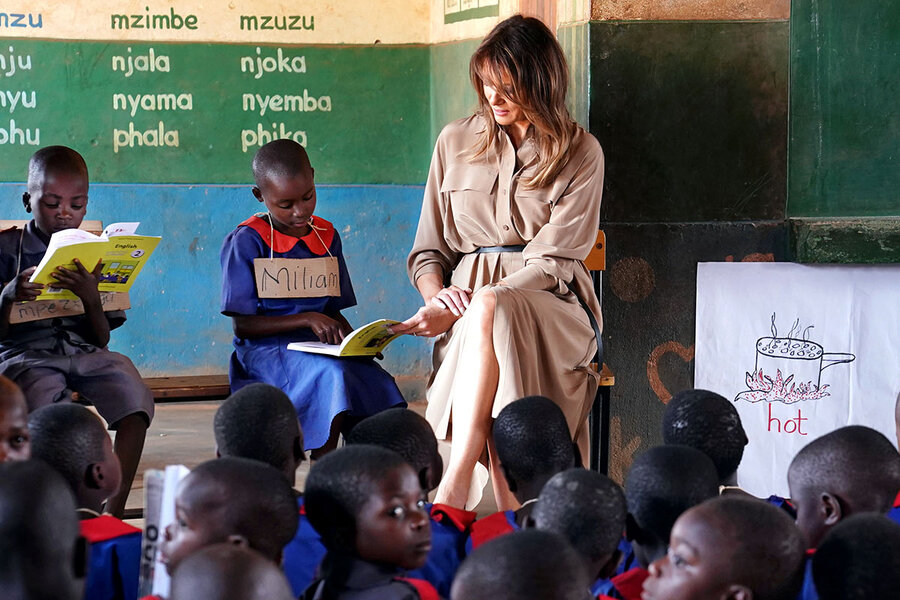

She held round-faced babies at a Ghanaian hospital and doled out books and soccer balls at an overcrowded Malawian school. She listened in solemn horror as a guide told her the history of Cape Coast Castle, a slave fort in Ghana, and laughed as she was nearly knocked over by a baby elephant she was bottle-feeding at a sanctuary in Kenya.

And then she put on the hat.

Why We Wrote This

Living and reporting in Africa, Ryan Lenora Brown writes, is a daily process of “unlearning” – of looking beyond the one-dimensional picture of the continent that so many Americans grow up with.

As Mrs. Trump prepared to board the safari vehicle that would take her on a jaunt through Nairobi National Park last Friday, she donned a white pith helmet – the domed, buckled hat fashionable among European colonists in Africa and Asia. (Think Meryl Streep in “Out of Africa.”)

Immediately, the internet was aghast. Had the first lady just made a sartorial nod to the good old days of colonialism, in full view of the world?

The next day, in front of the Egyptian pyramids at Giza, she tried to redirect the conversation.

“I want to talk about my trip and not what I wear,” Trump told the huddle of reporters traveling with her. “That’s very important, what I do, what we’re doing with [development agency] USAID, my initiatives and I wish people would focus on [that].”

In a sense, Trump was right to be irked. Critics had been looking for days for clues that the first lady didn’t really care about Africa, a region that her husband has mostly ignored – and occasionally mocked – during his presidency. They scrutinized her scripted visits to schools, tourist sites, and presidential palaces, where she was a quietly graceful visitor whose most common utterance seemed to be, “Thank you for having me.”

As a reporter working in Africa, I felt a flicker of sympathy for the first lady. Her choice of hat had been deeply silly, offensive even. But it likely was a gesture of ignorance, not malice. It simply mirrored the knowledge level of most people in the country where she lives – people for whom the helmet’s history was so unknown that it simply wouldn’t occur to them that she shouldn’t wear it.

Similarly, we often talk about Africa in such sweeping, at-arms-length terms that we might not pause when even thoughtful journalists refer to a country she visited, Malawi, as “obscure.” (Obscure, one wonders, to whom?) Or when all of Africa – a continent of 50-some countries and a billion people – is referred to as “vast and impoverished,” or when people who live there are “beloved and admired for having deep joy and resilience, in the face of issues like widespread poverty, disease and technological isolation, as is seen in some African countries.”

Indeed, one of the hardest things for me about reporting on this continent is that we are given a tacit permission to be simplistic, because few people challenge that view. And each time a figurehead visits to do charity and look at wildlife, they reinforce these perspectives. I suspect that Africa has long been a popular destination for first ladies, in particular, because it seems on the surface like a ready-made backdrop for American goodwill. It looks, from some angles, like an entire continent full of poor people and poor countries eager to be on the receiving end of American goodness. Often, as in Trump’s case, those recipients are children, a particularly sympathetic group. (Her trip was built around the “Be Best” campaign promoting children’s well-being.)

As I watched Trump’s trip from my home in Johannesburg, I wished that I could take her on a different kind of Africa jaunt. In the Ghanaian capital, Accra, for instance, I might have suggested she duck out of the presidential palace and pay a visit to a few artists’ workshops in the neighborhood of Teshie. There, she could have seen the sometimes wacky, sometimes profound whimsicality of the country’s famous coffin builders, who sculpt caskets in shapes ranging from cola bottles to lions to human-sized cell phones. In Kenya, instead of packing her day with visits to orphanages – first one for elephants, then one for humans – Trump could have taken a detour to the outskirts of the capital to meet Tegla Loroupe, a tiny powerhouse of a woman who broke nearly every distance running record in the world, and when she finished doing that, just as quickly began giving the money away. (Philanthropy, Trump could have pointed out to the Americans watching back home, can be homegrown, too.)

I think she might have even enjoyed the quintessentially West African experience of sitting in wheezing peak-hour traffic instead of speeding around it in her motorcade, watching as hawker after hawker streams by your car with a veritable supermarket of goods – donuts! Air fresheners! Inflatable pools! – balanced on their heads. The whole thing might have been a reminder of how hard and how creatively people work to survive any place where the system seems stacked against them.

I wish, in short, she could have seen Africa as I am privileged to be able to see it every day – as a staggeringly diverse and maddeningly complicated place. For me, unlearning the things America taught me about Africa will probably be a lifelong endeavor. I am still surprised by my own surprise at hearing, for instance, that Rwanda has three times the percentage of female legislators as the United States, that eastern Congo is well known for its cheesemakers, or that a bunch of teenage girls in South Sudan can kick my butt at dodgeball. Believing that a society or country or community can be many things at once – some of them dissonant and contradictory – is a privilege we grant freely to the places we come from. So why can we not also hold multiple Africas in our head as well?

The Africa Melania saw last week wasn’t fake. There are, in many countries on this continent, too many children crowded into underserved schools. There are too many animals being killed by poachers. There are too many dying babies.

But there are also artists and philanthropists and complicated, contradictory societies stumbling forward in the world. The same as in the United States. The same as everywhere.

Perhaps this trip – and that hat – will be the beginning of Trump’s own unlearning. If so, she and I are in that together.