In South Africa, a push to reclaim an Afrikaans as diverse as its speakers

Loading...

| Cape Town, South Africa

When a wave of student protests began crashing over South Africa’s universities in mid-2015, it didn’t take long to reach the doors of Stellenbosch University.

A stately campus nestled among the vineyards and mountains near Cape Town, with a student body that was 60 percent white in a country where nine in 10 people are not, “Stellies” was an obvious target for students angry with the educational status-quo. And its protestors had one grievance in particular: language.

“Being taught in Afrikaans, going to class and not understanding – these have all been part of how Stellenbosch has excluded me as a black student,” a PhD student named Mwabisa Makaluza explained to a South African paper at the time, referring to the local language that was heavily used by the apartheid government.

The implication was clear: Afrikaans was for white people. And since Stellenbosch still taught most of its courses in Afrikaans, it was slamming the door on students who weren’t.

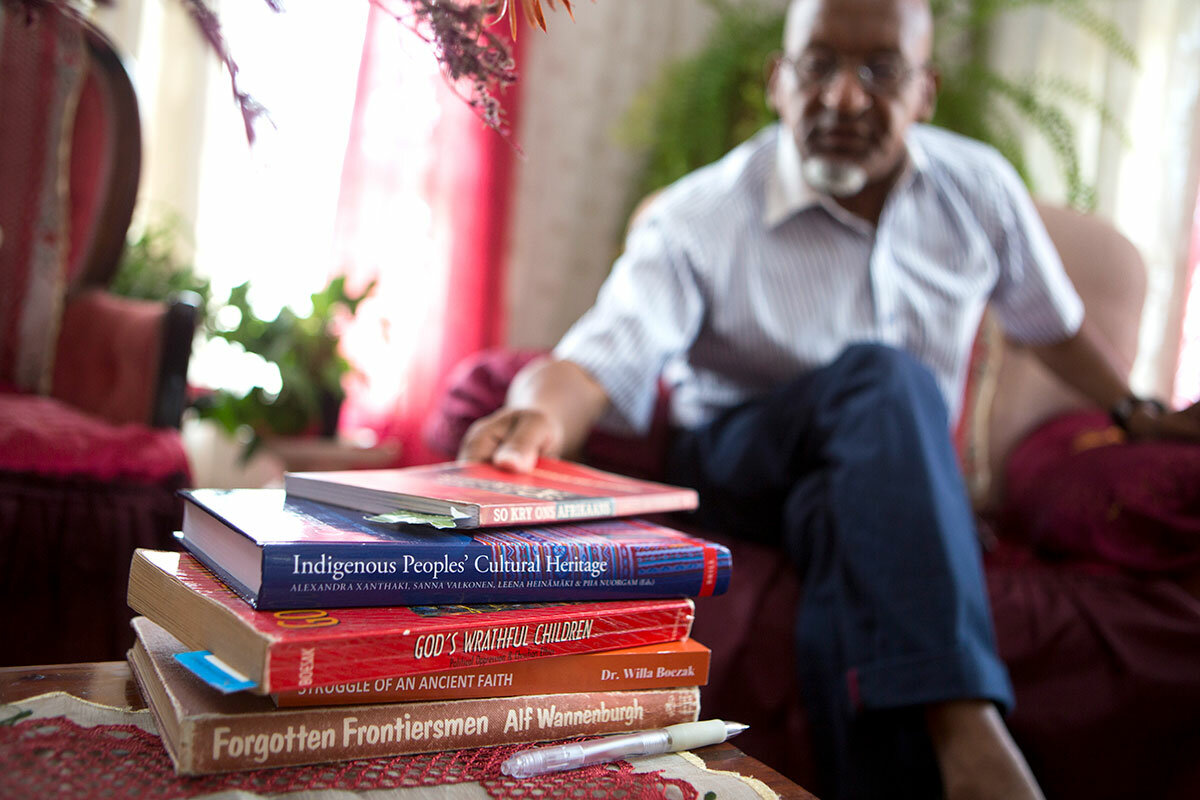

But as Willa Boezak watched the TV footage of protesters marching across the campus’s red brick paths, he didn’t quite see it that way.

It’s crazy this is what apartheid did to us, thought Dr. Boezak, a minister and activist for the rights of South Africa’s Khoikhoi indigenous community. It made us believe that white people actually invented Afrikaans, and that it’s their language.

The Dutch-based creole, he knew, wasn’t simply made up by white people. It emerged in the collision between Europeans, slaves, and indigenous people in southern Africa that began in the 17th century. But its bitter association with whiteness has “proven really hard to get rid of,” he says.

Of course, Afrikaans was more than a language in the protests. It was a shorthand for power. But to Boezak, it was telling that the discussion on campus had become, well, so black and white.

Like a growing group of activists, artists, and academics here, he is trying to complicate that story. Afrikaans was the language of white power in South Africa for a long time. But it was never just that, they say. It has a history as vast – not to mention as diverse, as violent, and as brazenly creative – as South Africa itself. And reclaiming that history isn’t just about making good on the blind spots of the past. It’s also about giving millions of South Africans reason to take pride in how they talk today.

“I wanted to feel proud to speak my mother tongue – the language I dream in, the language I heard in the womb,” says Janine Van Rooy-Overmeyer, better known as the singer, poet, and cultural activist Blaq Pearl. “Once I embraced where the language came from, I started to feel liberated speaking it.”

Worldwide roots

Like the majority of the 7 million South Africans whose first language is Afrikaans, Ms. Van Rooy-Overmeyer comes from a group of South Africans classified under apartheid as “coloured” – still a commonly used term today. Though she says she does not personally relate to the category, the term has long been a blanket description here for people of mixed race descended from indigenous Khoikhoi and San communities, Southeast Asian slaves, Europeans, and other African communities.

Their history, in a sense, is also the history of Afrikaans (literally “African” in Dutch), which grew from the encounter between those same groups of people at the southern tip of the continent between the 17th and 19th centuries.

In that violently cosmopolitan colonial world, masters needed a way to order around their slaves, and indigenous people needed a way to offer assistance and negotiate treaties with the new arrivals. And everyone needed a way to haggle.

A kind of simplified Dutch quickly became the language of war, money, and love in the early Cape Colony. And soon, it began absorbing words and syntax from both local languages and from Southeast Asian languages like Indonesian, the mother tongue of many of the area’s slaves.

Though most of Afrikaans’ vocabulary still came from the Netherlands, that wasn’t true of the people using it. In the mid-19th century, Muslim communities in the Cape became the first to write down the new language, using Arabic script and teaching it in their madrassas, or religious schools. Still, the language was often seen as lower class, and many Dutch speakers pejoratively called it “mongrel Dutch” or kombuistaal – kitchen language.

Language of repression, language of home

But as white Afrikaans speakers – many of whom had been on the continent for generations – grew more distant from their European roots, they began casting around for a new identity.

“They wanted to claim a history of their own, and to do that they needed a language of their own,” says Boezak. “The problem was that to do that, they had to steal from other people.”

In 1875, a group of Afrikaans-speaking white settlers announced the formation of The Society of True Afrikaners. Their main project was to standardize Afrikaans, which they called a “pure Germanic language.” Over the next few decades, they wrote dictionaries and published Bibles, children’s books, and nationalist poetry.

And as they did so, they quietly began to write “non-white” Afrikaans speakers out of history.

Afrikaans is “no mixed language, certainly not a mixed language that originated with Dutch speaking the Malay-Portuguese of the slaves,” wrote prominent linguist D.B. Bosman in 1916.

For decades, that became the largely accepted view in South Africa. In 1976, when the apartheid government tried to change the language of instruction in all South African schools to Afrikaans, massive protests erupted, with students wielding signs that read, in no uncertain terms, “TO HELL WITH AFRIKAANS.”

“As black Afrikaans speakers, we had to live with this double consciousness,” says Hein Willemse, a scholar of Afrikaans at the University of Pretoria, who was then a young academic and anti-apartheid activist in Cape Town. “On the one hand, it was quite clear that Afrikaans was the language of repression.” And it was often deployed to wound, he says, as when police used the informal version of “you” to address black people old enough to be their parents.

“On the other hand, Afrikaans – a different Afrikaans – was the language of home,” says Dr. Willemse, who recently wrote an opinion piece entitled, “More than an oppressor’s language: reclaiming the hidden history of Afrikaans.”

'Pride in who I am'

After apartheid ended in the early 1990s, Afrikaans’ status backslid. But the historical associations lingered.

In the Cape Flats – the sprawling miles-long sheet of sand outside Cape Town where millions of African, coloured, and Indian South Africans were resettled during apartheid – many young South Africans continued to grow up with the feeling that their version of Afrikaans was inferior and backward, since it sounded different from so-called “white Afrikaans.”

“When you go outside your community and see how other people react to the way you speak, you begin to feel like there’s something wrong with you,” Van Rooy-Overmeyer, the singer and poet, says. “And the impact of that hits deep. It has a really negative impact on the self esteem of an entire group of people.”

When Van Rooy-Overmeyer began her career as Blaq Pearl, she often sang and performed in English “because we were taught to see our own language as inferior.”

But that began to change in 2010, when she was invited to perform in a stage production called “Afrikaaps” – the name of the dialect of Afrikaans spoken in so-called "coloured communities" in the Western Cape. Performed entirely in this Cape Afrikaans by a troupe of well-known musicians from the Cape Flats, the play told a lesser known history of the language.

Afrikaans, sang Moenier Adams, one of the show’s performers, “is a history book without a cover, of a white guy looking for a brown skinned lover…. It lies in your blood and your history.”

The reaction to “Afrikaaps” was electric, Van Rooy-Overmeyer says. For many in her audiences, it was the first time they had heard Cape Afrikaans used so reverently. And for her, “it sparked a shift inside of me.”

Since then, she has devoted much of her professional life to teaching young people in those communities about the history of their language. But historian Saarah Jappie, who studies 19th century Arabic-Afrikaans manuscripts, says that story is still a surprise to many.

“When I show kids these manuscripts, so many of them say to me they had no idea this existed,” she says. “There’s this new sense of pride and ownership [in the language].”

Still, reclaiming history in contemporary South Africa is no simple task. Like everywhere, history’s mouthpiece here is the powerful – and many “coloured communities” here say they feel as excluded in the new South Africa as they did in the old. Then, they say, they weren’t white enough. Today, many feel told they’re not black enough.

In recent years, Afrikaans has become the flashpoint for conflict at schools and universities across the country, largely used as shorthand for the lingering remnants of apartheid that still hang low across many parts of South African society. (On average, white South Africans still earn nearly five times as much as black South Africans, and more than twice as much as coloured South Africans.)

Julius Malema, leader of the leftist opposition party the Economic Freedom Fighters, asserted last year that he “strongly believe[s] Afrikaans is being used to perpetuate white supremacy in South Africa.” Others argue that it is simply a minority language – taught in fewer schools, and to fewer students, than English – and doesn’t deserve the prominence it’s historically been afforded in South African society.

The view that Afrikaans is the language of white power in South Africa has left many coloured and other black Afrikaans speakers feeling marginalized, they say, even if they understand the roots of the complaint.

“This was the stupidity of apartheid – forcing Afrikaans on people” and making the language feel like their enemy, Boezak says. But for him and many others, it’s still a language worth preserving.

“When I perform in Afrikaans it really captures the essence of what I want to say – my culture, my identity,” says Van Rooy-Overmeyer. “It captures my pride in who I am, which is something I want to share.”