‘Bonfire of the incumbents’ unseats governments worldwide in 2024

Loading...

| London

It will be cold comfort for Kamala Harris. But American voters’ verdict in November – denying her the White House, and the Democrats a majority in both chambers of Congress – is typical of a major mood swing in democracies around the world.

The past 12 months have been dubbed “the year of the election.” A record number of voters have made their voices heard in some 70 countries. And in ballot after ballot, they’ve been reining in, or booting out, ruling parties.

The year of the election has become “the bonfire of the incumbents.” That’s true in the United States, as well as in European countries such as Britain and France. It’s also the case in in South Africa, where the ruling African National Congress lost its majority for the first time since the end of apartheid, and in Botswana, which has a new ruling party for the first time since independence 58 years ago.

Why We Wrote This

2024 was “the year of the election,” with around 70 countries going to the polls. But it also became the year that incumbents fell around the world. Can their replacements offer better solutions to voters’ problems?

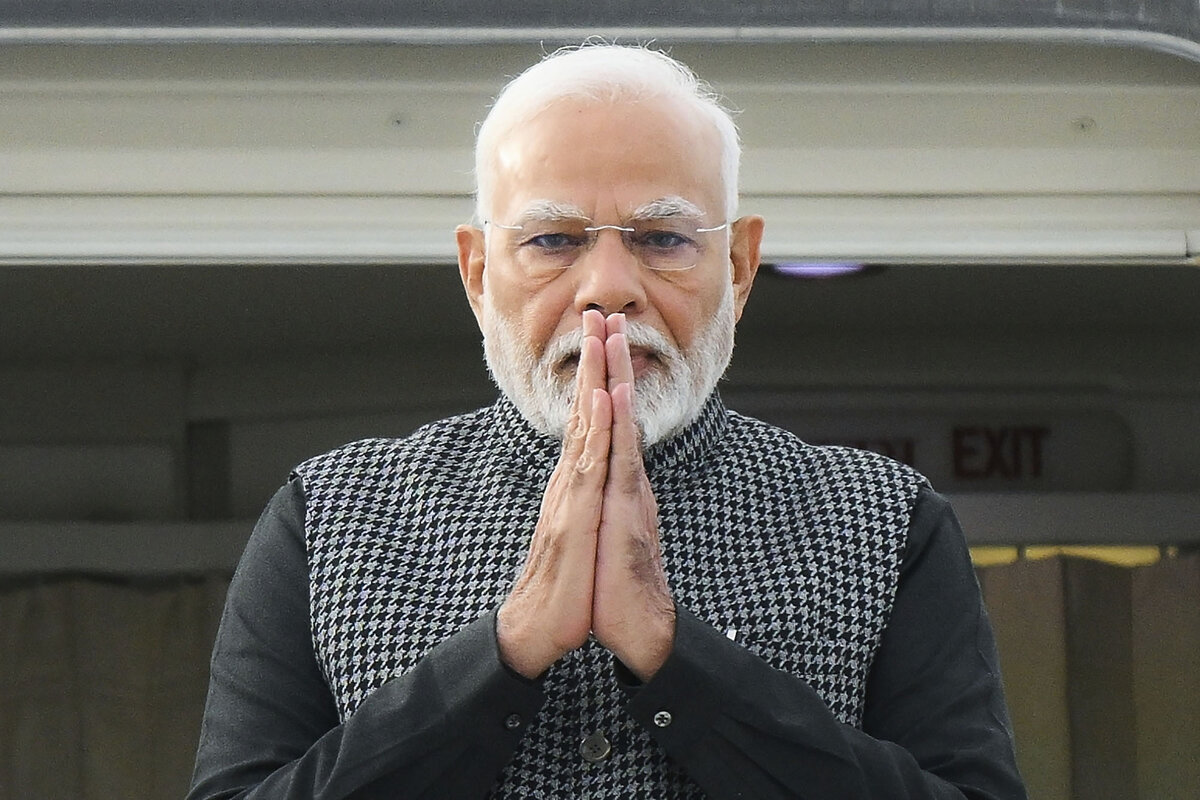

In Asia, Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party was unexpectedly stopped short of an outright parliamentary majority in India. Meanwhile, in South Korea this week, the president tried and failed to impose martial law in the wake of significant gains by the main opposition party in this year’s parliamentary elections.

With voters’ mood showing no signs of brightening in the new year, the impact of the anti-incumbent surge is being felt not only by the politicians, like Ms. Harris, who were sent packing.

There are signs – which the incoming Trump administration might well want to monitor – that the election winners are now finding themselves on the clock.

They face two daunting challenges.

The first is political: restoring democracy’s fundamental bond between governments and the governed. They know that if they fail, they, too, might find themselves on the bonfire.

The second is potentially even tougher. It’s about policy: addressing the main reasons for voters’ growing anger.

For while the mix of issues has varied from country to country, voters’ main grievances in nearly all the elections that punished incumbents were economic: stagnant or declining incomes, a lack of good jobs, and, above all, inflation.

And there is another hurdle that these governments have to surmount. Although they might be tempted to turn inward and get their own economic houses in order, the causes of much of the dissatisfaction are to be found abroad, in a battered world economy.

That economy is still recovering from multiple shocks, including the 2008 financial crash as well as the supply chain and inflationary effects of the pandemic and the Ukraine war.

Real wages in all the leading world economies are still lagging behind pre-Ukraine war levels, according to the United Nations International Labour Organization.

How, or whether, Donald Trump might pull back from some of his campaign pledges – steep import tariffs, for instance, could risk further fueling inflation – will become clear only once he takes office. He does enjoy one benefit that other newly elected world leaders can’t count on. The U.S. economy remains the largest and strongest in the world.

Still, the destabilizing effect of the anti-incumbent mood currently gripping voters is a concern for other politicians on the world stage.

Leaders in both Britain and France have been struggling to find a way to keep voters onside while also addressing serious weaknesses in their economies.

French President Emmanuel Macron still has a few years left in his final term. But his party took a battering in parliamentary elections this year, which has left him relying on the support of the far-right party of Marine Le Pen.

On Wednesday, she and her supporters in Parliament joined left-wing legislators and brought the government down in a no-confidence vote for the first time in 60 years.

In Britain, Labour Prime Minister Keir Starmer should be on much stronger ground. His party was handed a huge parliamentary majority when voters there called time on 14 years of Conservative Party rule in July.

Yet ever since his government unveiled tax rises and spending cuts aimed at reinvigorating a stagnant economy, his poll numbers have nose-dived.

Appointing a new head of the civil service this week, he sounded a note of urgency, clearly aware of the need to achieve real change before too long: “nothing less,” he declared, “than the complete rewiring of the British state to deliver bold and ambitious long-term reform.”

In gauging his chances of pulling that off, he may be casting an eye toward another beneficiary of voters’ growing anger. It is a leader from the opposite side of the political spectrum, on the opposite side of the world.

Argentine President Javier Milei, a flamboyantly outspoken libertarian, won power late last year in a landslide victory on the promise of a root-and-branch remaking of government to rescue the country’s crisis-ridden economy.

He, like Mr. Starmer, has sensed the need to move quickly and show results.

He has already managed a three-quarters reduction in inflation, which had been raging at a rate of 13% a month, in part by eliminating half of the government’s ministerial departments and slashing public spending by one-third.

Some of the spending cuts have reduced state subsidies on basic goods and services, vital for a large number of Argentines. Poverty is on the rise.

The key question will be whether the voters will stick with him, even in the face of economic pain, at least in the short term.

Yet so far at least, not only has he avoided a Starmer-like collapse in his poll numbers. His popularity is on the rise.