Adam Smith's hidden hand of empathy

Loading...

| London

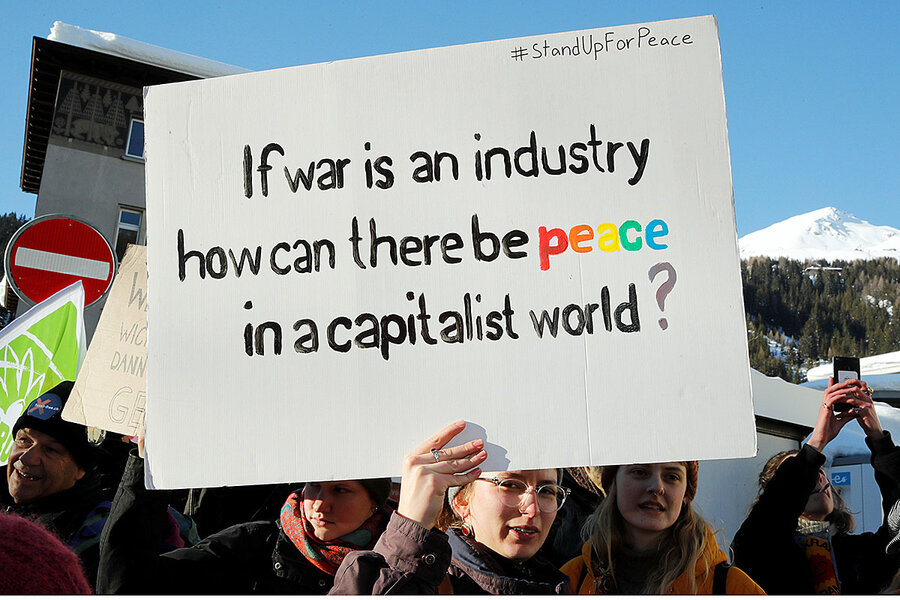

The “s” word – socialism, that is – has returned to American politics, with President Trump signaling in his recent State of the Union address that he sees it as a key weapon against the growing list of Democratic Party candidates for the White House.

But while the label of “socialist” has long been seen as toxic in US politics, that could be changing. Some of Mr. Trump’s rivals are indeed advancing radical proposals for taxation and regulation on the very richest. Yet they’re part of a wider, growing trend affecting many Western democracies.

It’s not a drive for socialism in the classic definition of the term: replacing market economies with state ownership and control. It’s a search for answers to a problem even mainstream politicians increasingly acknowledge: Free market capitalism has ceased to work the way it used to, or ought to.

Why We Wrote This

The "socialist" label has reentered US politics – and it tends to evoke radicalism. But across Western democracies, including the US, the debate around it is becoming decidedly more nuanced.

The policy debate differs from country to country. But the core issue is the same: the huge economic power residing in a very few individuals and corporations at the top, while others – not just at the bottom but also in the middle – struggle to get ahead of just stay even in a world economy that’s changing beyond recognition.

Until the market crash of 2008, the West’s governing consensus favored broadly business-friendly policies over explicit efforts to tackle wealth disparity. Today’s climate is different. A well of economic resentment has helped fuel the rise of populist politicians, Trump among them. In Italy, a populist coalition won power by promising, among other things, a guaranteed minimum income. In Britain, Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May took office vowing to address the plight of working-class families. The opposition Labour Party wants a tax increase on the wealthy and new worker protections, especially for those in the so-called gig economy.

In France, President Emmanuel Macron has responded to a wave of street protests by approving $12 billion in new support for pensioners and the least well-off. He also plans to use this summer’s annual meeting of the Group of Seven of major industrialized nations to press for an internationally agreed-upon minimum tax on the largest companies – including the technology giants – to keep them from finding low-tax countries that shield them from paying.

What we’re seeing is not the first major challenge to capitalism, a system whose roots go back 250 years to the writings of Scottish philosopher Adam Smith. In his “Wealth of Nations,” first published in 1776, he argued that through the “invisible hand” of a free market, the pursuit of self-interest would lead to prosperity for all. But he also posited an underlying strain of human empathy, presumably tempering excesses by some individuals at the expense of others. That’s where the strains emerged, especially with the Industrial Revolution and during the Depression of the 1930s. Over time, they led to a range of corrective measures, including antitrust and labor-union laws, and the growth of the modern welfare state.

The latest challenge has been building since the 1970s due to a web of factors: deregulation, corporate takeovers, the rise of increasingly complex forms of investment banking, and the focus of individual companies almost exclusively on profit for their own shareholders. But the seismic jolt came with the emergence of a truly global and increasingly high-tech economy that, while yielding undeniable benefits, left a huge proportion of national and international wealth and influence in the hands of a very few. The 2008 crash – and the bailout of banks and businesses needed to keep it from becoming even worse – dramatized this.

Trump’s speech earlier this month took aim at proposals from such presidential hopefuls as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D) of Massachusetts and Sen. Bernie Sanders (Ind.) of Vermont for new taxes on the very richest Americans and regulatory action against what they see as corporate or banking excesses. Trump’s calculation seems to be that branding his rivals as “socialist” will conjure up powerful visions of Soviet Communism or the collapse of Venezuelan socialism in voters’ minds.

He may yet prove right. But the changing political climate seems to have had an effect in the United States as well. A recent Fox News poll, for instance, found that even a majority of registered Republicans now favors higher taxes on the

very rich.