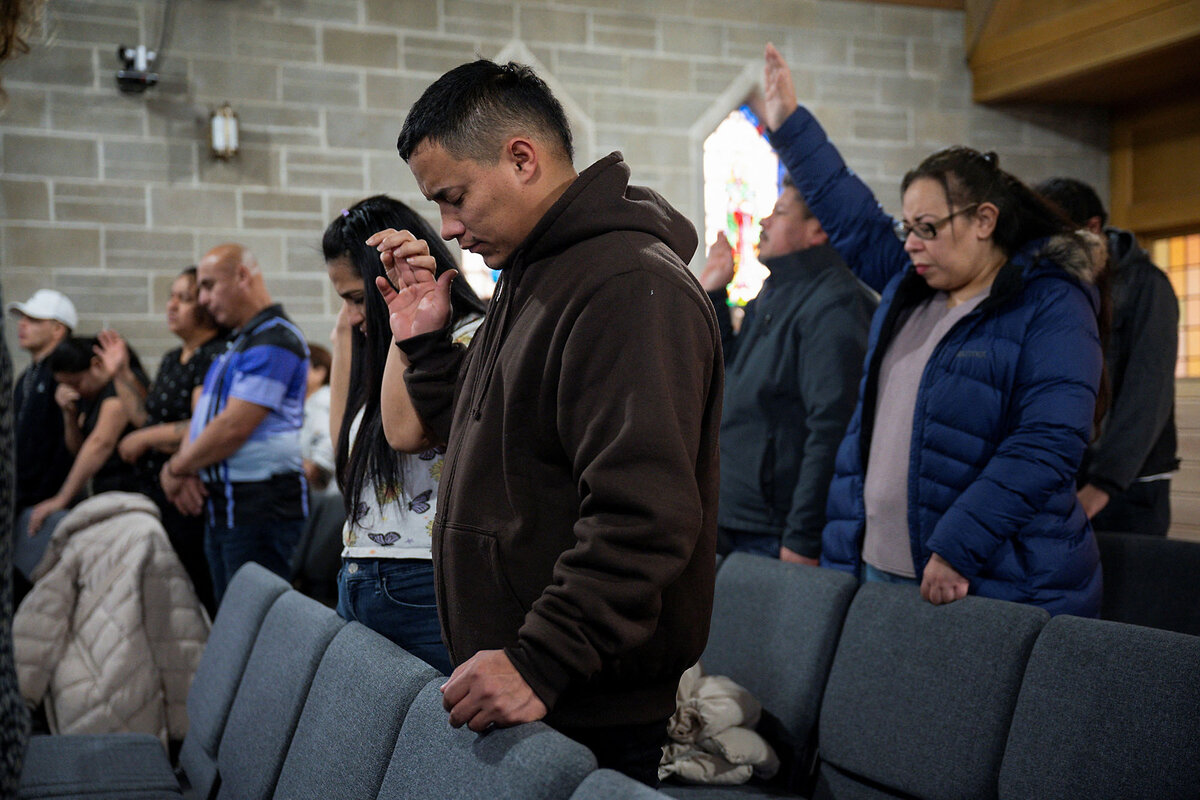

‘People will be afraid to go to church.’ Congregations sue for sanctuary.

Loading...

| Washington; Tucson, Ariz.; and Denver

Is sanctuary covered by the First Amendment? In the wake of new Trump administration orders, religious denominations are arguing that it is.

On Monday, five Societies of Friends sued the Trump administration over a directive on immigration, saying it infringes on their religious liberty.

When the Department of Homeland Security announced it would no longer recognize churches as “protected areas,” many religious leaders around the country objected. Offering refuge to the vulnerable is central to their faith practice, they say. Guidance in previous presidencies advised against conducting immigration enforcement at or near sensitive locations, including houses of worship and schools.

Why We Wrote This

Offering refuge to the vulnerable is central to their faith practice, many congregations say. But is the tradition of sanctuary legally covered by the First Amendment?

“[The guidance] suggests that they might go into churches or schools or hospitals as a matter of routine enforcement,” says Matthew Soerens, national coordinator for the Evangelical Immigration Table. He notes that President Trump didn’t withdraw the protected area guidance, which had been in place since at least 2011, during his first term.

“The most significant impact of this change in policy is that people will be afraid to go to church,” says Mr. Soerens, whose organization wrote a letter signed by seven Christian groups urging the Trump administration to respect religious freedom.

That’s exactly what many houses of worship are concerned about, whether or not raids are conducted. And that’s part of what the Quakers say constitutes a violation of the First Amendment.

Quaker meetings can’t operate without freedom to sit together in worship and receive and share messages from God, says Christie Duncan-Tessmer, general secretary of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, one of the plaintiffs.

“Enforcement in protected areas like houses of worship would, in the government’s own words, ‘restrain people’s access to essential services or engagement in essential activities,’” reads the suit, brought by Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and four other Societies of Friends.

In Texas, the state supreme court recently heard arguments in a similar case. The Texas attorney general is trying to shut down Annunciation House in El Paso, arguing that the Catholic organization can’t use religious beliefs as a defense for sheltering unauthorized migrants. Annunciation House, for its part, is suing the state for violating its religious freedom.

“The State must show it has a compelling state interest for its action burdening religious practices, and that its action is the least restrictive means of achieving that purpose,” writes David Hacker, senior counsel at First Liberty Institute, in a statement to the Monitor. First Liberty filed an amicus brief in support of Annunciation House with the Texas Supreme Court.

It’s not clear how the courts are likely to rule in either case. Both suits cite the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), passed in 1993 to protect individual religious practice. And, as some legal scholars point out, case law relating to RFRA and the First Amendment has strengthened in recent years, to the benefit of religious groups.

The right of religious groups to deny services to same-sex couples has been upheld, says Rose Cuison-Villazor, director of the Center for Immigrant Justice at Rutgers Law School.

“What does that mean now in the immigration context? That’s the really big question,” she says.

Whether courts will recognize offering sanctuary as a First Amendment right is yet to be seen. However, some legal scholars say that lawsuits brought by faith groups during the pandemic over shutdown orders could provide a guide.

In some of those cases, courts decided the government was too closely targeting religion, says Gregory Magarian, a law professor at Washington University School of Law. But, he adds, if a church simply says that providing shelter to people is part of its religious mission, the free exercise clause doesn’t stop the government from enforcing the law.

Why the change in enforcement?

The earlier guidance limited not just arrests in sensitive spaces but near them, with limited exceptions.

The policy eliminated “whole neighborhoods” where U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement could operate, says John Fabbricatore, former field office director in Denver.

The guidance “wasn’t rescinded so that they could go into schools and churches,” he says. “It was rescinded so they can actually go into neighborhoods to make arrests of actual criminals without violating the policy.”

ICE did not respond to the Monitor’s questions about how enforcement in and around places of worship will change under the new guidance.

“Criminals will no longer be able to hide in America’s schools and churches to avoid arrest. The Trump Administration will not tie the hands of our brave law enforcement, and instead trusts them to use common sense,” reads a Jan. 21 press release from the Department of Homeland Security.

Entering the United States illegally is a misdemeanor on the first offense. Residing in the U.S. unauthorized is a civil violation.

Birthplace of a movement

Historically, sanctuary was intended for the guilty, says Karl Shoemaker, a legal historian at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. “In the American context, we tend to see sanctuary as a kind of safety catch for people that are caught up in a larger machinery of bureaucracy.”

Over the past decade, faith communities around the country designated themselves sanctuary communities in response to immigration enforcement, with a particular surge in 2016 during the Syrian refugee crisis.

It has long been a daily practice at Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona, the church often credited as the birthplace of the 1980s Sanctuary Movement. Seeing the U.S. deny asylum to nearly all Guatemalans and Salvadorans at that time, churches and volunteers at the border organized to provide assistance and temporary shelter. Southside alone aided more than 13,000 Central Americans fleeing war.

When she joined the congregation in 1984, Leslie Carlson remembers asylum-seekers sleeping on the floor of the church through the week. “I knew the church was doing something very risky and very faithful to the Gospel,” she recalls.

Today, Southside continues to organize shelter with other congregations, as well as offer resources like training sessions on how to be an ally to unauthorized immigrants.

Some churches might hold the value of sanctuary but not have the facilities to offer refuge to people, says Joel Miller, the pastor of Columbus Mennonite Church in Ohio. His church was a sanctuary congregation during the first Trump administration.

The reference to sanctuary means more than the specific act. It also refers to “how we treat one another,” he says.

Mr. Miller doesn’t ask about people’s identity when they come through the door. “Theologically we understand everyone as created in the image of God and as having dignity and the sacredness of humanity that we all carry,” he says.

Historical roots of sanctuary

For several thousand years, different traditions have offered sanctuary as a way of holding a sacred space where daily administration and bureaucratic law were suspended “in recognition of something higher, something more holy,” says Dr. Shoemaker, of the University of Wisconsin.

The tradition of houses of worship providing sanctuary predates Christianity, and was practiced in pagan temples. It appears in sacred texts, including the Torah and the Christian Bible.

Mr. Miller, the pastor in Ohio, points to words in Leviticus, the source of the adage “love thy neighbor.” A few verses away, he says, is a related command: “The stranger that sojourneth with you shall be unto you as the home-born among you.”

“This memory that we try to nurture in religious communities in our congregation is remembering that we all have a story about having come from some place of need,” he says. It’s important to “not forget that we were in that position and that now some of us are in a position to offer that to others.”

Sanctuary isn’t a formal concept in the Quaker faith, says Ms. Duncan-Tessmer. But based on the belief that “everybody is a child of God and is an expression of God,” she says, “everybody needs to be protected and welcomed and cared for from that perspective.”

As the enforcement implications of the new policy take shape, church communities could be put to a test they haven’t been for some time, says Dr. Shoemaker.

Many faith leaders who have consulted him on sanctuary aren’t willing to put up active resistance if officers enter, he says. “But they want to do everything they can, short of resistance, to protect their congregations.”