In sports, what’s fair for transgender athletes and their competitors?

Loading...

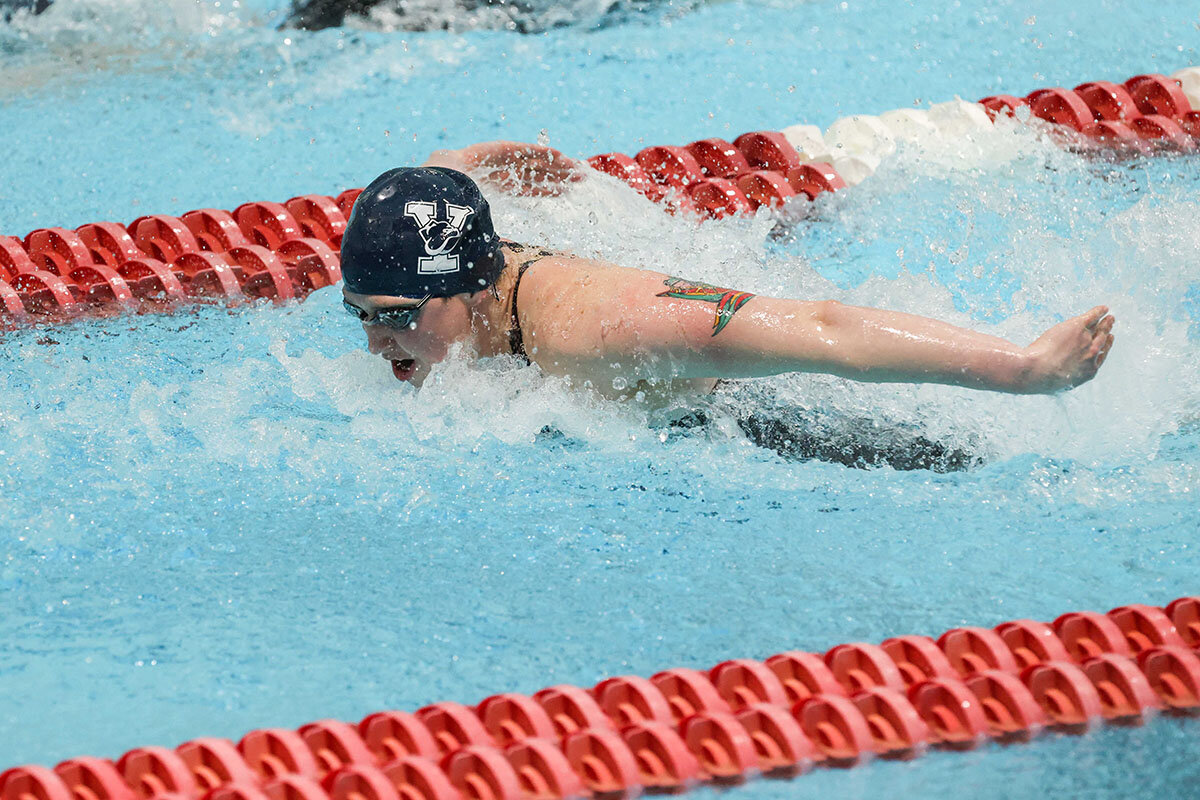

At a recent Ivy League swim meet, spectators were split over which side of the pool to look at.

At one end, several women jackknifed their bodies in flip turns for the final lap of the 500-meter freestyle. Their furious kicks churned the water and left white vapor trails in the sky-blue pool. On the other end, a swimmer named Lia Thomas had already finished and broken the Harvard pool record. In the 7.5 seconds it took for the second-place swimmer to arrive, Ms. Thomas adjusted her swimming cap, took off her goggles, and took in the scene around her. In an online video of the race, which has been viewed over 5 million times, a visible banner near Ms. Thomas’s lane bears the slogan “8 Against Hate.”

The sign, meant to oppose hatred of any kind by the eight Ivy League Universities, is a form of support for Ms. Thomas, a transgender woman. She’s made a splash not just in her sport but in the tempestuous culture wars. The fifth-year senior at the University of Pennsylvania has tallied record-setting wins in her first season competing in the women’s category. In a new and rare interview, Ms. Thomas told Sports Illustrated, “I want to swim and compete as who I am.”

Why We Wrote This

Swimmer Lia Thomas’ participation in the NCAA’s national championships this week offers an opportunity to discuss the experience of transgender athletes and to consider what constitutes fairness when it comes to their inclusion in sports.

A number of people believe that Ms. Thomas should not be eligible to swim in the women’s category at this week’s NCAA Division I championships in Atlanta. They claim that she has an outsize advantage – not just in her considerable height, but also in physical strength having gone through male puberty. Others hail the athlete as a trailblazer for LGBTQ rights. They believe that Ms. Thomas, as a transgender woman, should be allowed to swim in the women’s category. The high-stakes controversy – affecting women’s sports, Title IX, and even the Olympics – has spawned strident op-eds and social media posts by those who support and oppose Ms. Thomas’ participation.

It’s a sensitive subject that many people are afraid to discuss publicly. But a good-faith debate is also underway. Sports figures, researchers, and observers are offering competing visions of how to preserve fair competition while also facilitating maximum inclusion within those parameters. Their conversations may ultimately influence how the public and sporting bodies think about these issues.

“There’s a really good debate going on among intellectuals with integrity, about whether we should be trying to balance fairness and inclusion or continuing to center fairness and allowing as much of inclusion as possible within that structure,” says Doriane Coleman, a professor at Duke Law School who studies how evolving definitions of sex affect institutions such as sports.

A swimmer and a divided country

Those debates are taking place at a time when trans issues have become a prominent front in politics. In Florida, Republican Governor Ron DeSantis is expected to sign a bill into law that would, among other things, prohibit classroom instruction, especially in younger grades, “about sexual orientation or gender identity.” Legislators in Idaho are moving forward with a bill that would make it a felony for parents to help with gender-affirming health care – like hormone therapy – or to take their children to another state for medical procedures related to gender transitioning. In Texas, a new directive to investigate parents for child abuse who help their transgender children transition was temporarily stayed last week by a judge. Last month, South Dakota banned transgender girls and women from participating on female teams in school and college sports. It joins a growing number of states barring trans young people from school sports.

Ms. Thomas has become a proxy in these battles.

“I just want to show trans kids and younger trans athletes that they’re not alone,” the economics major told Sports Illustrated. “They don’t have to choose between who they are and the sport they love.”

Ms. Thomas, who is from Austin, Texas, started swimming at age 5 and swam competitively in high school. Some believe that this week she could break college records set by Olympic icons Katie Ledecky and Missy Franklin.

Sports Illustrated says that “the most controversial athlete in America” has become a “right-wing obsession.” Yet the controversy over Ms. Thomas doesn’t neatly fit into a right-versus-left culture war, says Cyd Zeigler, co-founder of Outsports, a publication that focuses on LGBTQ issues and competitors in sports.

“People who think that trans women should be treated as women in employment, in housing, in education, on their driver’s license, can all agree on that and supporting her – and, at the same time, say she doesn’t belong in women’s sports,” says Mr. Zeigler.

He has observed that many people in the LGBTQ community – including some who are transgender – do not believe Ms. Thomas should be competing in the women’s category.

Last year, a Gallup poll found that 62% of respondents believe that athletes in competitive sports should “play on teams that match birth gender.” Among Republicans, 83% agree with that statement, among Democrats, 41% agree, and among independents, 62% agree.

In the media and on social media, debates about Ms. Thomas often get nasty. In response, Lucas Draper, a transgender male athlete on the swimming and diving team at Oberlin college, penned a guest editorial in Swimming World Magazine. He called for civility and human decency in conversations about the athlete.

“No matter what your stance is on whether transgender athletes should be allowed to compete, it takes no real effort to at least identify them properly,” says Mr. Draper in a Zoom interview. “I didn’t think that it was fair that people were targeting Lia because she’s following the [NCAA] rules as they were set out.”

Requirements to swim

In elite sports, the rules governing transgender athletes are in flux at an international and national level. Various sports bodies have traditionally tested the testosterone levels in transgender athletes. (Similarly, many professional sports prohibit the use of anabolic steroids, which is a synthetic testosterone that boosts muscle mass and strength.)

The NCAA has historically required that transgender women undergo at least 12 months of testosterone suppression prior to competing in the women’s category. A longtime competitive swimmer, Ms. Thomas began hormone replacement therapy in 2019, two years prior to entering the women’s category, which met the NCAA’s requirements.

In January the NCAA announced it would leave requirements for transgender athletes to the national governing body of each sport. USA Swimming responded by setting new rules. It required a threshold of testosterone tests as well as a requirement that transgender athletes submit evidence to a panel that they do not possess an unfair biological advantage over non-transgender competitors. The NCAA subsequently decided that changing its rules midseason was unfair, which will make Ms. Thomas eligible to compete in this week’s tournament.

“There is a minority of extremely loud, extremely influential people who are pushing for no transition requirements,” says Mr. Zeigler. “Those people have a lot of influence in the NCAA.”

The NCAA did not respond to requests for comment.

The International Olympic Committee recently indicated that it is going to scrap its testosterone test requirement. That may be a boon for Ms. Thomas, who says that she’s aiming to qualify for the Olympics.

Those who oppose limiting the participation of transgender athletes contend that it’s not clearly established that testosterone confers an advantage for transgender athletes. Others in the academic community strenuously disagree, pointing to numerous primary research studies on muscle strength and muscle mass.

Joanna Harper, a Ph.D. student and researcher at the School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences at Loughborough University in the U.K., sits somewhere in the middle of those two views. Her first-ever case study? Herself. When she started her hormone therapy treatment in 2004, she began logging the rapid decline in her performance times as a competitive long-distance runner. Similarly, since Ms. Thomas started hormone therapy in May 2019, her performance times have slowed. But Ms. Harper says that even after testosterone suppression, transgender athletes are going to maintain some strength advantage.

“My initial paper was a study of distance runners,” says Ms. Harper, who has become a prominent voice in conversations about transgender participation in sports. “Strength doesn’t really matter for that sport, but strength does matter for swimming. So Lia will maintain both height and strength advantages over the cis women that she’s swimming against.”

Ms. Harper believes that eligibility shouldn’t just be purely determined by gender identity. She’s an advocate for factoring in testosterone levels. That stance has drawn the ire of some LGBTQ activists.

“I’ve been called ‘a traitor to trans people,’” she says.

Gregory Brown, a professor of exercise science at the University of Nebraska Kearney, believes that the focus on testosterone is ultimately too narrow. He says that those who’ve gone through male puberty tend to be taller and have larger wingspans, larger body mass, larger muscle fibers, larger hearts, and larger blood vessels.

“A trans woman still has XY chromosomes,” he says. “And there are effects of the Y chromosome that are very important to keep in mind as far as how the physiology works and administering hormones doesn’t necessarily negate those effects.”

Ms. Harper counters that the hormone therapy transition may actually create disadvantages for transgender women athletes, such as reduced muscle mass and a loss of aerobic capacity. The lower level of hemoglobin in blood also diminishes athletic performance. For her, any remaining biological advantages that Lia Thomas has are within a reasonable parameter.

“But the difference is not so large that it endangers women’s sports at all,” says Ms. Harper.

What would “fair” look like?

This year, Iszac Henig, a Yale swimmer who is a transgender man, has competed several times against Lia Thomas. Although he has had chest reconstruction surgery, he has not begun taking testosterone because he wanted to be able to continue competing on a women’s swim team.

To some, the coexistence of the two transgender swimmers in the same race brings into question the meaningful differences between men’s and women’s events.

“The same advocates who say Lia Thomas belongs in the women’s category, will also say that Iszac Henig belongs to the women’s category and belongs in the men’s category,” says Mr. Zeigler from Outsports. “How can somebody belong in both the men’s and the women’s category at the same time?”

Meanwhile, 16 of Ms. Thomas’s teammates sent an anonymous letter to their school and Ivy League officials contesting the swimmer’s right to swim in the category because of “an unfair advantage.” Several parents of swimmers on the team have also expressed their disquiet over the effect on the sport in anonymous interviews with the press.

To some, the biological debates over just how large or small an advantage transgender athletes may or may not have ultimately leaves too much margin for error. It would be fairer, they say, to simply draw the line between those who have and haven’t gone through male puberty.

Yet some sports thinkers have been mulling the question of whether it’s possible to preserve the women’s category – and at the same time facilitate opportunities for transgender athletes.

Nancy Hogshead-Makar, a former gold medal Olympic swimming champion and now a civil rights lawyer at the Women’s Sports Policy Working Group, opposes Ms. Thomas’s inclusion in the women’s competition. Instead, she proposes a Solomonic solution. She says transgender athletes such as Ms. Thomas could still compete in an exhibition race (in which her results would not count). It’s the swim meet equivalent of auditing a class.

But that idea doesn’t sit well with some.

“[I]n a way, what it does is put more focus on Lia Thomas, and I don’t think it’s great for them because it sort of ‘others’ them,” says Jon Pike, former Chair of the British Philosophy of Sport Association and a senior lecturer in Philosophy at The Open University in Milton Keynes, U.K. “If there’s eight lanes when you’re using one lane as an exhibition lane for Lia, then someone else could be in that lane, and you are, in fact, still excluding someone … for a result that won’t count.”

Mr. Pike has an alternate proposal. He recently co-authored a paper with Leslie Howe, a professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, and Emma Hilton, a biologist at the University of Manchester in the U.K., titled “Fair Game.” They believe it’s vital to exclude transgender women from the female category at elite levels of sports. Ms. Howe, a feminist philosopher, believes it isn’t fair to the other swimmers.

“I have a fair bit of experience in the past, as a lesbian, in participating in gay tournaments,” says Ms. Howe, who enjoys sports such as rowing. But, she adds, when it comes to mainstream sports, “it doesn’t matter what your sexuality is or your identity. When we get into playing, it’s about the bodies competing against each other, and we have to make those categories fair.”

Many sports – with the exception of, say, shooting and sailing – already factor what types of bodies are competing with each other, adds Mr. Pike. It’s the reason why adults don’t compete against kids or the reason why there are senior categories in golf and marathons. Weightlifting and boxing each have weight classes. Other games, such as the Special Olympics, include impairment categories.

To maximize inclusion, the trio proposes that the men’s category of sports be replaced by an “open” category that would include transgender athletes.

“You do not have to declare yourself to be a man in order to compete here,” says Mr. Pike. “We are not going to say, ‘You’re in the men’s competition.’ We’re going to say you’re in the open competition.”

Ms. Harper’s response to the idea is unequivocal: “No, I just can’t go along with that,” she says.

“Trans women are not men who think they’re women,” she adds. “Our gender identity is such a fundamental part of who we are.”

These different perspectives seem, perhaps, fundamentally irreconcilable. But Mr. Brown believes that, as Ms. Thomas’s story becomes more of a talking point in society, it will spur calls for various sporting bodies to institute compatible rules and a stable framework. He’s optimistic that if such debates continue in good faith, and if there’s willingness to make concessions, then it may be possible to agree upon an optimal solution.

“It’s to a certain extent like compromise in marriage,” he says. “If you’re saying you’re compromising in your marriage and you’re happy with the way things turn out every time, you’re not compromising. So that’s what we’ve got to have here - is that people are going to be willing to say, ‘OK, I’m not going to be 100% happy, but I’m going to get a compromise that I can live with happily enough.’”