Is any conflict unsolvable? This author doesn’t think so.

Loading...

Amanda Ripley does not like to think of any conflict as unsolvable. Her new book, “High Conflict,” reveals that progress is possible even in the most bitter, entrenched, and violent clashes.

The genesis for Ms. Ripley’s book was the political divide in the United States. She began wondering how ordinary people become mired in extreme, yet commonplace, polarization. It’s the type of strife that keeps people awake at night, encourages them to start flamethrower tirades on Twitter, or entices some to cut off relationships with friends and family. In what she terms high conflict, one imagines adversaries as evil and less than human.

Ms. Ripley, an investigative journalist for The Atlantic, went searching for examples of people and communities who had been stuck in high conflict and found a way out. That quest led her to meet with Democrats in New York City and Republicans in rural Michigan. In the rival gang territories of Chicago and in civil war-torn Colombia, Ms. Ripley met individuals who’ve put down their guns and now help others to extricate themselves from violent disputes. She even consulted experts for NASA who work on diminishing conflict among crews of astronauts in space.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe pull of conflict can be hypnotic. But in her book “High Conflict,” Amanda Ripley explores how it is broken by genuine listening. As part of our Respect Project, she talks with the Monitor about how we can all find practical ways forward.

Ms. Ripley describes high conflict as an invisible force with a hypnotic pull. The initial reason for various disputes becomes less important than the self-perpetuating, us-versus-them battle that takes on a cosmic importance for those in its thrall. The Monitor spoke with the author about how to become aware of high conflict, how to avoid getting drawn into it, and why the dry kindling for conflagrations can be dampened by showing genuine respect for others.

Q: Can you share your thoughts on why respect for others is so important to mitigate conflict?

There are different conditions, or fire starters, that tend to lead to high conflict. One of them is the extreme opposite of respect, which is humiliation. Evelin Lindner, the psychologist and physician who studies conflict and war, calls humiliation the nuclear bomb of the emotions. It’s probably the most underappreciated force explaining international crises, domestic violence, gang warfare. All manner of high conflict often is really, at some level, about feelings of humiliation. One thing that I’ve learned is to never embarrass your opponents. It just backfires. It may feel good to you, but it just hits at the core of our human need to belong and to matter.

Q: Sometimes we lose sight of respecting others – how does that happen?

Distance makes it easier for us to caricature each other, and we don’t know each other. And at the same time, we are also quite capable of caricaturing someone we know very well. So it’s not just a function of distance, although that’s often the case with political conflict or ethnic conflict where there’s segregation.

There’s a few things that I find speed up that process. One of them is “conflict entrepreneurs.” There are people around you, or platforms, or pundits who are exploiting the conflict for their own ends, that can really accelerate that disrespect. Conflict entrepreneurs can get us into oversimplifying or categorizing each other.

Q: One of the solutions to high conflict is something called contact theory. What’s the basic idea behind it?

Contact theory is the idea that people from different groups will, under certain key conditions, tend to become less prejudiced towards one another after spending time together. And it is really the most studied, proven intervention for prejudice.

It’s also a delicate art. So it doesn’t mean we should just take people of different races or religions and put them in a summer camp together. That has been tried many times. Interaction with the other side is not enough. Just because we play basketball together does not just lead to more understanding all by itself. It’s ideal if people don’t just talk, but actually work together on some kind of common problem. It triggers our instincts for cooperation rather than competition. What problem are they going to solve together that they both care about? That creates a third identity outside of the conflict. And we know it’s a lot easier to create a new identity than to get rid of an old one.

Q: How important is truly listening to others? How does that engender trust and respect?

I’d been a journalist for almost 20 years when I started working on this, and I’ve interviewed thousands of people from all walks of life. I thought that I was listening. I got schooled pretty quickly in my first mediation training where I was told to try to actively listen to someone and play back what I thought they had said that was most important to them. And then check if I got it right.

When you do that – which is one of the listening techniques called looping for understanding – what you find is a couple of things. First, it is hard to keep your head and your mind focused on what is most important to that person, not to you. We make all these cascading assumptions about what someone’s talking about, what they mean, what they’re going to say next, and we’re frequently wrong. So that’s why it’s really good to check if you got it right and then try again.

When you do get it right, this almost magical thing happens where the person’s whole posture changes, their face lights up, and they say, “exactly.” When people feel heard like this, they behave differently. They say more nuanced things afterwards, less extreme things. They admit to more internal ambivalence. They’re more open to ideas and information they didn’t want to hear.

Q: Do you have any recommendations about what individuals can do to avoid getting pulled into that vortex of high conflict on social media?

One thing to do is to just distance yourself from the conflict entrepreneurs in your feed if you’re on Facebook or YouTube or whatever. Also realize that the skills required to talk about conflict online are not intuitive. I do a lot of looping now online. If someone challenges me and seems to be doing it in good faith, I will say, “It sounds like you feel that I’ve oversimplified this problem. Is that right?” And then I’ll try to take it off Twitter to DM [direct messaging], so it’s not public. Or, ideally, if you know the person, you want to talk on the phone, but you could also email them. Make them feel heard first – genuinely heard. And then you can get somewhere more interesting and you might learn something. So I definitely engage differently. I try to really resist the urge to have a sort of clever comeback.

Q: Can you tell us how some of the individuals in your book practiced a loving, respectful outlook for others even if they still had fundamental differences and disagreements with them?

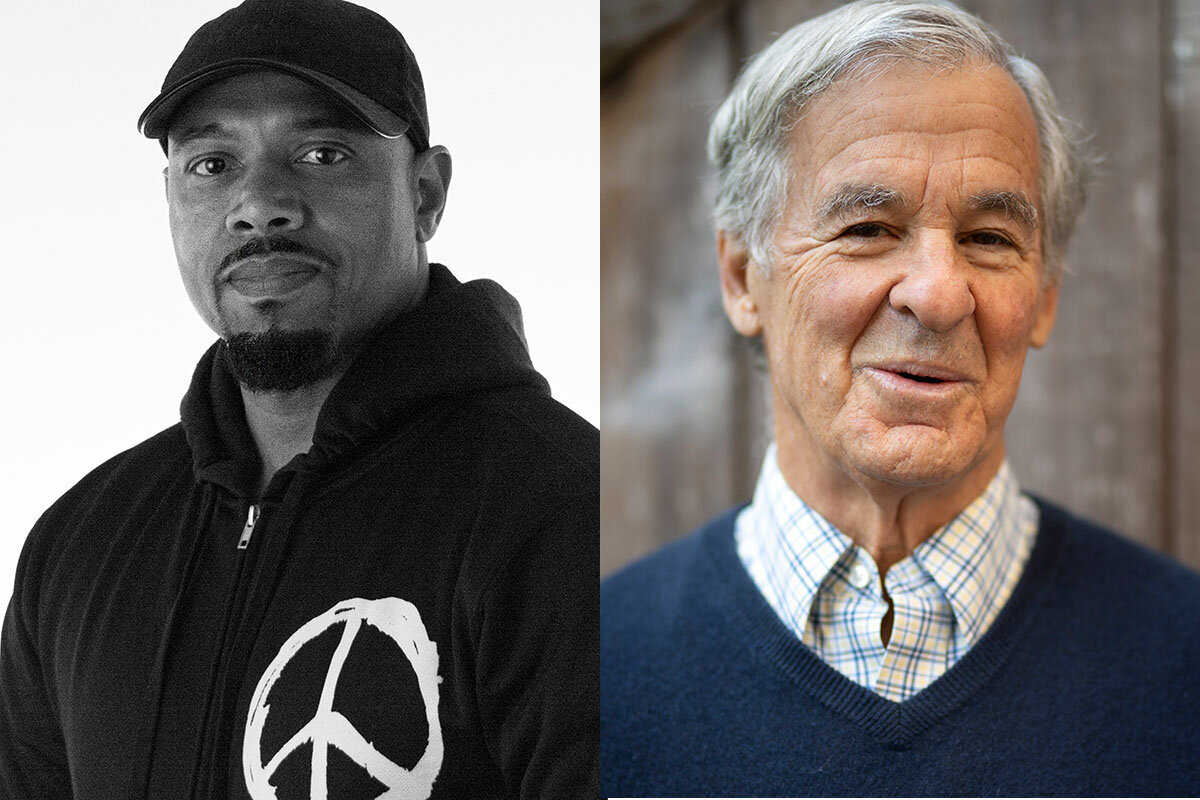

There are some cool tricks that I’ve learned from the conflict survivors featured in the book. One of them is Curtis Toler, who was a fairly high-ranking gang leader in Chicago and now works with at-risk young men and women in Chicago, to help them make the same shift he made out of that conflict, but make it more quickly. He said that sometimes he will imagine the person he’s talking to as a tiny child, which we all were at one point. And literally in his mind, try to bring them back to that 3-year-old. It’s a way for him to access their humanity. To see them the way they once were, and a way they could be again, a sort of innocence.

Gary Friedman, who was the conflict expert who ran for office and immediately got ensnared in high conflict, actively engages with people he disagrees with in his neighborhood. He’s really into gardening. His other neighbor, with whom he often disagrees, is really into gardening. So he tries to build up the balance in the ledger books by genuinely talking with authentic interest about her roses. It’s not fake. It’s important that you’re not faking it. But it’s a way to complicate the narrative in his own mind, and in her mind, about who the enemy actually is.

Q: You describe the alternative to high conflict as good conflict – a situation in which you disagree with the other person but you still have a basic respect for them that allows for productive dialogue. Can you describe what that sort of respect looks like?

When you cultivate good conflict between people who are extremely divided, people want more of it. There’s almost a transcendent feeling that arises even in deep disagreement.

Martha Ackelsberg – a very engaged, progressive Jewish activist in New York City who ended up going on a homestay exchange with rural Trump supporters in Michigan – has a great way of putting it, which is why I ended the book with her quote. I’m going to read it.

“I feel like it’s brought out the best in me,” Martha told me and I knew exactly what she meant. I have had the same feeling, a sense of being fully alive in good conflict. And then she says, “I wish I could appear everywhere in my life the way I felt called to appear in these two times” – that’s on those exchanges she did – “present, open, able to be surprised.”

And so you see the distinction there. She’s not surrendering; she’s not agreeing. She’s not engaged in bipartisan unity, nor is she avoiding the conflict. She feels like the person she wants to be – arguing, wondering, revising, awakening to something you hadn’t understood before.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.