Why the ’70s are a blueprint – but not a destiny – for the 2020s

Loading...

| Washington

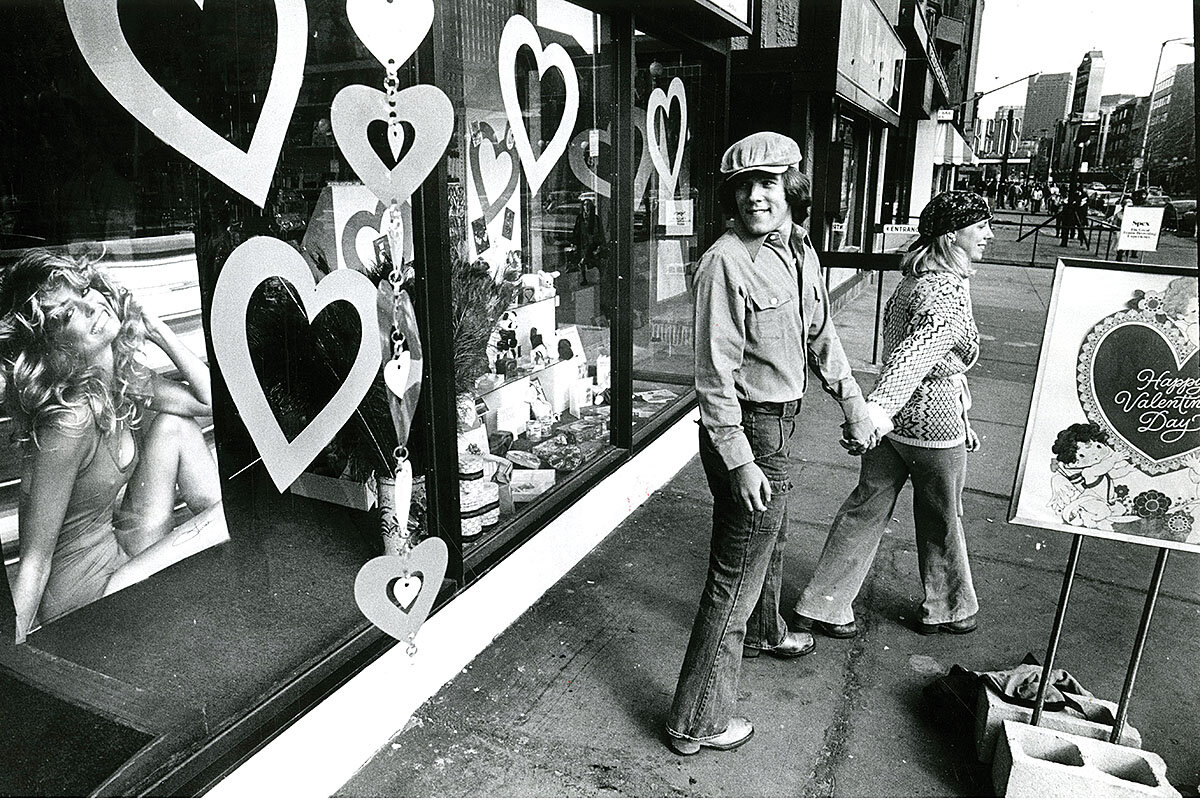

Protests. An ugly withdrawal from a botched foreign war. Inflation. Politics riven by anger and partisanship. Puff-sleeve peasant dresses. Shortages of consumer items. New music from ABBA.

This was the 1970s – and perhaps also the early 2020s. History often runs in cycles, and four decades after Watergate and the debut of “M*A*S*H,” the United States at times seems to have gone forward into the past, with the retreat from Afghanistan evoking the flight from Saigon, Black Lives Matter protests echoing ’70s civil rights and anti-war marches, and a spike in the cost of living reviving painful memories of a decadelong economic malady known as “stagflation.”

Remember vinyl LPs? They’re back, and if not bigger than ever, then big enough: They’re the music industry’s most popular and highest-grossing physical format. Swedish 1970s pop legend ABBA released “Voyage” in September, and it’s now the fastest-selling vinyl release of the century. Bucket hats are back, too, in all their floppy glory. Target’s even selling a tie-dye version. Loose-fitting pants are called “flares” now, but that shouldn’t fool anybody. They’re bell-bottoms by another name.

Why We Wrote This

The 1970s, which hold many parallels to the 2020s, offer lessons for how to handle social strife and problems of today. But the differences between the two decades also show how far society has evolved in key areas.

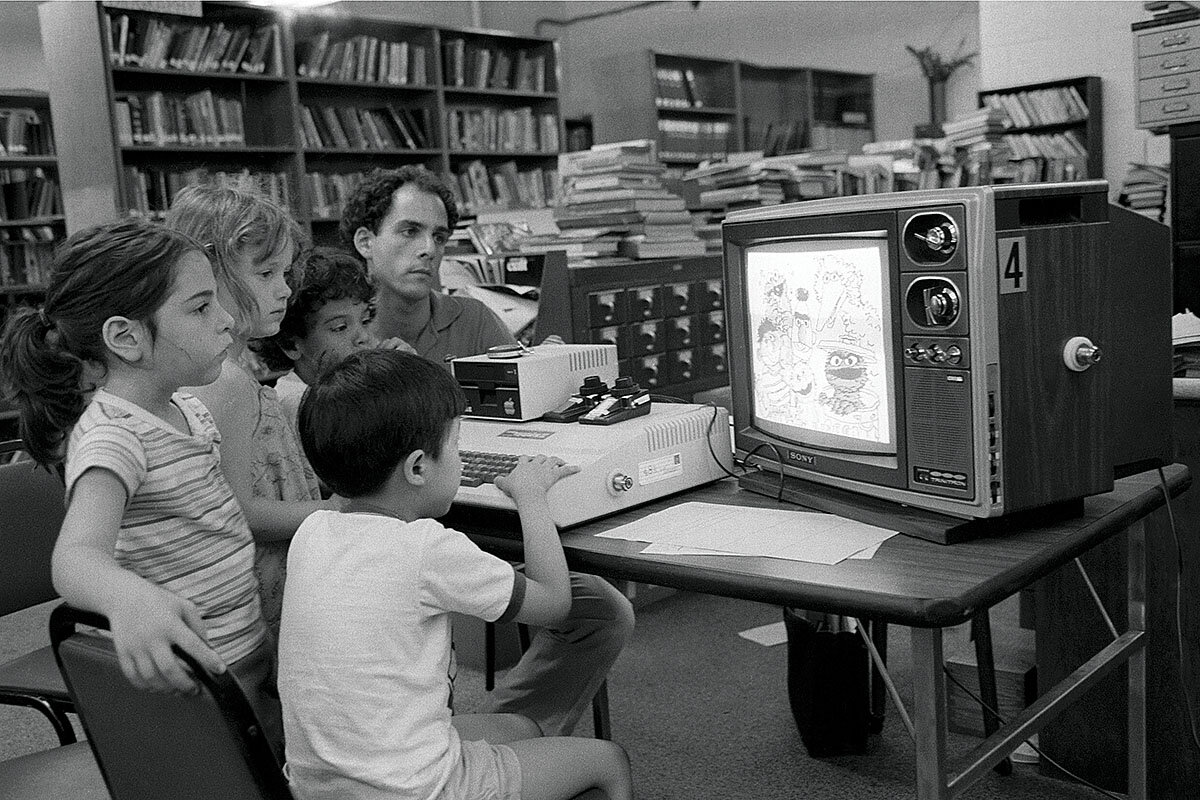

The 1970s and early 2020s are far from twins, of course. They differ in ways both small and profound. A half-century ago, the nation still had a common culture, with TV shows and music and mainstream news that most of the population consumed. The Vietnam War was seismic in the extent it spread disillusion and distrust in government. COVID-19 has no parallel in U.S. history since the influenza pandemic of 1918. Smartphones and social media have led to technical and cultural revolutions.

But the 1970s struggled with new kinds of challenges that needed new and creative fixes, and the 2020s may, too. They had gas lines; we have supply chain shortages. They had a generation riven between hippies and “squares,” and we have one split between progressives and conservatives. Crime rose then, and it’s rising now. Both eras have been infused with a feeling that the nation is on the wrong track. Dare we call it “malaise”?

The question is whether today’s leaders will be better than those of the past at solving things, instead of muddling through. Today the nature of the U.S. population is far different. It’s much more diverse than 40 years ago. It’s also more fragmented than the years when “All in the Family” could draw 20 million households an episode.

You could consider that change a roadblock to consensus and solutions, says Bruce Schulman, professor of history at Boston University and author of “The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Politics, and Society.” Or you could judge it as a way to bring new thinking and points of view to bear. “You can see that as presenting a set of opportunities about different ways to deal with those problems,” he says.

Americans not old enough to remember the decade of the 1970s might think of it as transitional, a trough between the high energy of the boisterous 1960s and the high “morning again” optimism of the early Reagan years. At the time some chroniclers agreed with this low regard. Journalist Tom Wolfe famously dubbed it the “Me Decade,” a time of rampant narcissism.

“It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times,” wrote the editors of New West magazine. They proposed that the decade be officially ended in 1979, “one year early and not a moment too soon.” In truth it was more eventful than these gibes suggest. In politics, the country was fashioning the foundational reforms of the post-Watergate era, while three great “-ism” movements continued to accelerate: consumerism, feminism, and environmentalism, the latter of which couldn’t be properly practiced without wearing Earth shoes.

The decade had some cultural heft, too. The Beatles’ last studio album, “Let It Be,” was released in 1970. Much of the fashion associated with the ’60s was actually introduced – or reached its apotheosis – in the early and middle years of the ’70s. Bell-bottoms moved into the Middle American mainstream, popularized by “The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour.” Clothing morphed seamlessly into the satin and sequins of the disco era after the film “Saturday Night Fever” came out in 1977. Will any of today’s popular songs have the staying power of “Let It Be?” Would any TV show or movie now move mass fashion?

In the 1970s, “there was much more of a common culture,” says Dr. Schulman. “You might not have watched ‘M*A*S*H’ or ‘Mary Tyler Moore’ or ‘All in the Family’ in the 1970s, but it’s almost impossible that you would not have been aware of them. Whereas now I’m sure that you are watching things that I’ve never even heard of.”

At the same time, the 1970s saw artists begin to reject the model of the mass audience and develop alternative and iconoclastic followings. Disco, punk, and new wave music arose as a counterweight to KISS, Alice Cooper, and other stadium acts. Method acting and cutting-edge films such as “Taxi Driver” were direct counters to blockbuster movies such as “Jaws.”

“I think we see a lot of similarities to that kind of pop cultural struggle of the 1970s in the environment that we have today,” says Dr. Schulman.

U.S. troop involvement in the Vietnam conflict began in the early 1960s. But the heaviest American bombing of the long Indochinese war, dubbed Operation Linebacker II, occurred in December 1972. Anti-war protests roiled the U.S. that same year.

Vietnam was a central issue in the 1972 presidential election, as it had been in 1968. By ’72, the U.S. public would no longer tolerate sending large numbers of troops composed partly of draftees to fight in Southeast Asia. But President Richard Nixon’s strategy of “Vietnamization” didn’t work. Saigon fell to advancing North Vietnamese divisions in April 1975.

As South Vietnam collapsed, Vietnamese who had worked with Americans and members of the country’s elite besieged evacuation points, including the U.S. Embassy. The desperate even clung to helicopter skids in bids to escape. It was an inglorious episode echoed by the frantic crowds fighting to get past the perimeter of the Kabul Airport during the fall of Afghanistan in 2021.

In both Vietnam and Afghanistan, the U.S. learned a bitter strategic lesson: For local troops, the will to fight is more important than Western military equipment, training, and money. On paper Saigon and Kabul were set to defend themselves. In reality the departure of American power proved catastrophic to their forces’ morale.

That said, Vietnam was a defining issue of its era in a way the Afghanistan War has never been. The toll was much higher – U.S. combat deaths in Vietnam were about 47,000, as opposed to some 2,000 in Afghanistan. It was a much more divisive political issue, as thousands took to the streets of America to oppose the war. U.S. radio was filled with anti-war protest songs, such as Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Ohio,” about the Kent State University shooting of four protesters by the Ohio National Guard in 1970 (“Tin soldiers and Nixon’s coming, we’re finally on our own”).

The “forever war” in Afghanistan lasted 20 years, eroding trust in government and the U.S. military. But overall “the disillusionment seems bigger and more thorough with Vietnam than it does with Afghanistan,” says Kevin Mattson, a professor of contemporary history at Ohio University in Athens and author of “‘What the Heck Are You Up To, Mr. President?’: Jimmy Carter, America’s ‘Malaise,’ and the Speech That Should Have Changed the Country.”

With the year-end shopping season, President Joe Biden faces a crisis both material and political – bare shelves. The great supply chain blockage of 2021 has stacked up container ships at ports, pallets in U.S. warehouses, and boxes in retail backrooms. Everything seems in short supply, especially if it comes from Asia: electronics, clothing, auto parts, even the chains and buckles foresters use to stabilize old tree limbs.

Mr. Biden vowed to alleviate the situation in time for Christmas. He’s pushed to unclog ports and ease truck driver shortages. But his political problem is that there is only so much he can do. Private firms control the supply chain, and many of the blockages are caused by larger forces, such as the surge in demand from consumers in the wake of COVID-19 vaccinations.

What he hasn’t, and probably won’t, do is what President Jimmy Carter did: try to get ordinary Americans to look inward and examine their role in the shortages’ creation. Yet Mr. Biden’s overall situation bears some similarities to that once faced by Mr. Carter. “I think that Biden’s in kind of the same place ... as Carter was at the end of the ’70s, feeling kind of trapped,” says Dr. Mattson. “No matter what he does, there’s going to be an immediate pileup of criticism.”

Whether the 1970s was a transitional decade or not, Mr. Carter might fairly be judged a transitional chief executive. Elected following the Watergate scandal as an antithesis to the disgraced President Nixon, Mr. Carter was replaced after one term by a president who in many ways was his opposite in demeanor and politics, Ronald Reagan.

Gas lines, not empty shelves, were Mr. Carter’s supply crisis. The U.S. had already gone through an energy panic in 1973 when OPEC had raised prices in response to the Yom Kippur War between Arabs and Israelis. Then in 1979 Iran ousted the shah, who was replaced by a theocratic administration. Iran’s oil production dipped. Consumers, perhaps spooked by the previous shortage, rushed to fill up. Gas prices spiked again.

The second oil shock, on top of the first, seemed to threaten a pillar of the American dream. Pretty much every car on U.S. roads was still a gas guzzler by modern standards, and Americans were dismayed to find that cheap gas and V-8s were apparently no longer their birthright. “The people out there are getting frantic,” said the protagonist in John Updike’s novel set in the period, “Rabbit Is Rich.” ”They know the great American ride is ending.”

As gas stations instituted sales restrictions, Mr. Carter canceled a scheduled energy speech and retreated to Camp David, where he spent 10 days meeting with civic, religious, and political leaders. He reemerged with an address that touched on the energy crisis – and also unemployment, inflation, and a nebulous “crisis of confidence.”

“We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of unity of purpose for our nation,” he said.

The speech was daring. It said all the legislation in the world couldn’t fix what ailed America. Citizens shared responsibility for the nation’s problems, and they needed to look within to see how they had come to define themselves by what they owned. In essence, the problem wasn’t a shortage of gas, but an excess of materialism.

Delivered on July 15, 1979, the speech was initially a great success, boosting the president’s poll numbers by 11 points. Then he fired his Cabinet two days later, and the subsequent uproar swamped his message. Today it is remembered as the “malaise” speech (a word Mr. Carter never used) and as a downer of a presidential message.

Both Mr. Carter and Mr. Biden have preached personal responsibility as a solution to U.S. ills, says Dr. Mattson. Mr. Carter urged citizens to buy less gas. Mr. Biden has urged them to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Both tried to lead by example, with Mr. Carter turning down the White House thermostat and Mr. Biden getting vaccine shots on-air.

That might speak more to the distrust people feel toward Washington than to either of them personally, says the Ohio University professor.

Besides supply problems, the 2021 U.S. economy has begun to experience another unfortunate trend that blighted the 1970s. No, not the return of wide neckties – inflation.

Today the price of everything from cars to cantaloupes has surged as the economy roars back from its pandemic depths and consumers rush to make purchases they have put off. More money chasing insufficient goods is the classic recipe for inflation.

The rise was something of a surprise. A recent Bloomberg survey of economists predicts inflation at the end of 2021’s fourth quarter will measure 5.8% over the previous year, up from a forecast of 5.3% only a month earlier.

To those who lived through the 1970s, such creeping numbers might inspire creeping worry. Starting at about 2% in the late 1960s, inflation rose to 12% in 1974 and 14.5% in 1980. The cost of mortgages and other consumer loans skyrocketed.

You’d go to look at a car that cost $5,000 and decide it was too expensive. A short time later, the same car was $10,000. “Back in those days, things would double in price over relatively modest periods of time. ... We haven’t really seen that in recent decades,” says Scott Sumner, chair of monetary policy with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

The inflation era finally ended after Mr. Carter picked Paul Volcker, a bald, fly-fishing, 6-foot-7-inch economist to run the Federal Reserve. Mr. Volcker raised the rates the Fed charged banks to borrow funds, clamped down on the money supply, and tamed the inflation rate. The cost was a severe economic recession.

Most economists don’t think inflation today will be as virulent as in the 1970s. Goods are rising in price today, not services. Manufacturers also have strong incentives to iron out their supply chain problems, and the pent-up demand driving many of the high costs now may not last.

“For young people that haven’t experienced the ’70s, this might seem like a lot of inflation,” says Dr. Sumner. “For someone like me, it seems more like a one-time burst of inflation that’s not that dramatic.”

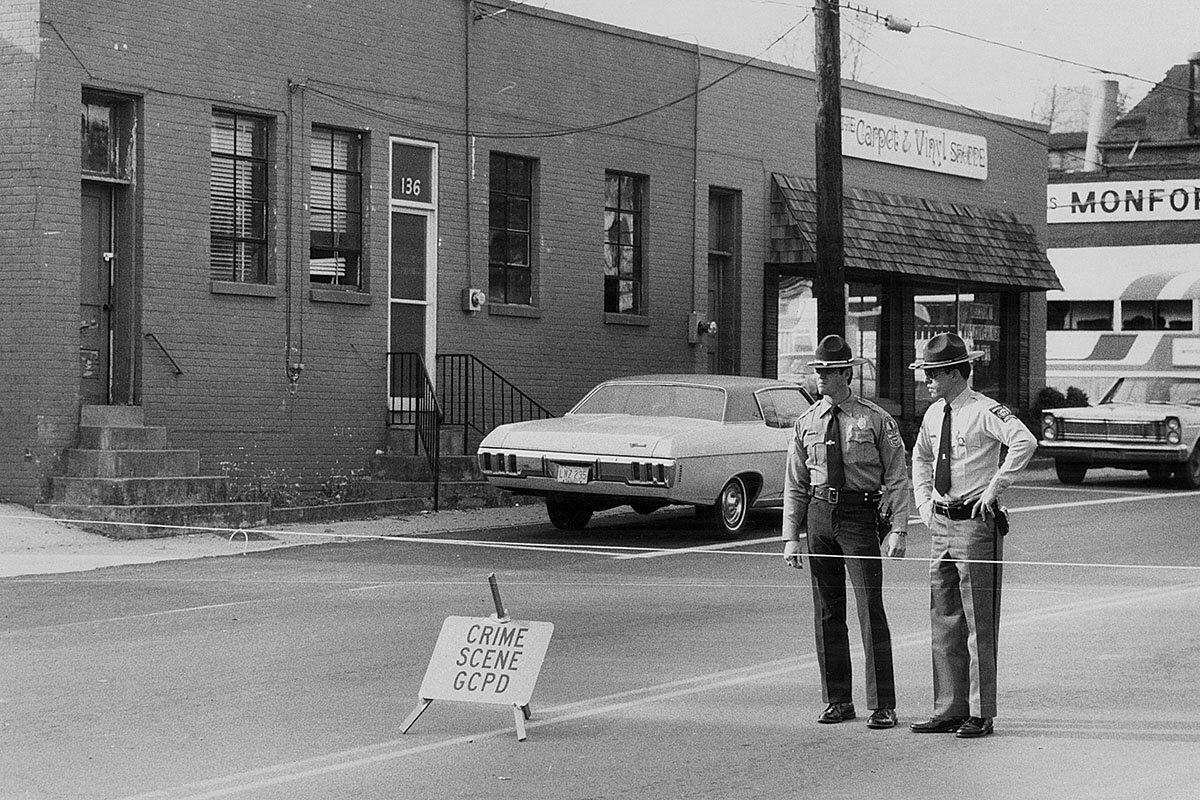

The Black Lives Matter protests that filled American streets following the death of George Floyd, a Black man, under the knee of a white police officer in Minneapolis were a phenomenon likely unmatched in U.S. history. Polls suggest that 15 million to 26 million Americans engaged in BLM demonstrations in nearly 550 locations across the U.S. By some measures that makes them the largest social movement of all time. Most of the marches were peaceful. Some ended in violence.

The protests of the 1970s were intense but not as pervasive. The era of marching for civil rights peaked in the 1960s and lasted only into the early ’70s. In that sense they are an example of what some historians call “the long ’60s” – an extension of the previous decade as much as a feature of their own. The protest energy of the 1970s was directed into anti-war demonstrations – at the 1971 May Day march in Washington, D.C., police arrested 12,000 people, likely the largest mass arrest in the U.S.

Even so, there are still useful comparisons to make between the end of the 1960s and early ’70s civil rights demonstrations and those of today. Start with the makeup of the activists.

“One really big difference between the 1960s and ’70s to now is the degree to which the protest movement is integrated,” says Omar Wasow, an assistant professor of politics at Pomona College in Claremont, California, who studies protests and race.

White people were on the front lines of the older civil rights movement, and some of them put their bodies on the line. But today they make up a larger share of racial justice protesters, and are more likely to have sophisticated views on race, says Dr. Wasow. “That reflects a kind of broadening of the coalition of support,” he says.

Another difference is social media. Activists in the 1960s and 1970s had to copy flyers and spread them around churches and other civic meeting places to muster a crowd. Today they can do that with a tweet. But this ease comes with costs – it may rally more people who feel less strongly about a cause. It also makes it easier for people who may want to sabotage or counter the demonstration to join in.

“It’s easier to mobilize, and it’s also easier to infiltrate,” Dr. Wasow says.

A final difference is the increase in political pressure and political division. Social media means people have fewer secrets – and perhaps no sideline on which to stand and just observe what’s going on. Young people especially feel they live in a panopticon, where they are watched at all times. They have to choose one side or the other. Thus a backlash to any movement is ensured, according to Dr. Wasow.

“If there’s a Black Lives Matter movement, then almost by definition there’s going to be something that steps in to fill the [role of] the anti-Black Lives Matter movement,” he says.

“Culture was ahead of politics in the early 1970s in reflecting the way the country was changing, and I believe that we are in a very similar situation now.”

So says Ron Brownstein, a veteran Washington journalist who is currently a CNN analyst, writer for The Atlantic, and author of “Rock Me on the Water: 1974 – The Year Los Angeles Transformed Movies, Music, Television, and Politics.”

Back in the ’70s, shows like “M*A*S*H” and “Maude” spoke to and reflected the way the country was changing at the time, says Mr. Brownstein. The former was set in the Korean War, but everybody knew it was really about the turmoil surrounding Vietnam. The latter, a spinoff of “All in the Family,” dealt with women’s rights, racial equality, and other topical themes.

Those same sorts of progressive and diverse appeals are on TV today, according to Mr. Brownstein, even in something as banal as a burger ad. Beginning in the 1970s studio heads, music executives, and corporate marketers began to realize that they had to reflect the country’s demographic and social changes to remain relevant. They knew they had to cater to different tastes – first the baby boomers, now millennials and Generation Z.

“You are seeing the reality of an increasingly diverse audience and workforce creating pressure for more diverse storytelling,” says Mr. Brownstein, who often writes about demographics and their effects on broad U.S. trends.

Politics is on a different timetable, perhaps. When the “Maude” run began in 1972, President Nixon was about to win a second term as president, taking 49 states. His platform generally stood against the cultural change that “Maude” espoused.

While an effective campaign appeal, his cultural message didn’t accomplish its goal. Gender and racial change came to America anyway, Mr. Brownstein notes. Now former President Donald Trump is gearing up for a 2024 run that leans heavily on promises to “take back” a changing nation. Win or lose, he won’t be any more successful in that attempt than President Nixon was, says Mr. Brownstein.

“I think very much what will be the lesson of now is that while you can build a political majority around the idea of stopping the change, what you can’t actually do is stop the change,” he says.

There’s repetition in history, no doubt. In fashion, the old often looks new again. In politics and economics, similar problems can arise at regular intervals.

To those who lived through them, the 1970s were like today in that the nation had a similar feel of anger and polarization. This abated somewhat after Watergate played out and President Nixon resigned. But now the nation is led by a Democratic president with sinking poll numbers who may simply be a transition figure. Sound familiar?

Mr. Biden is in fact a physical link between the eras. He was elected a U.S. senator from Delaware in 1972 and has been a Washington insider ever since. But under the surface far more is different now than the same. Different demographics and coalitions power U.S. politics. The economy is vastly bigger and dependent on different industries. Visual art and music take old tropes and cut and mix them in new ways.

When it comes to the 1970s and 2020s, the past may not really be prologue. It may be more of an outline and a few notes, from which valuable lessons nonetheless can be gleaned.

Dwight A. Weingarten contributed to this report.