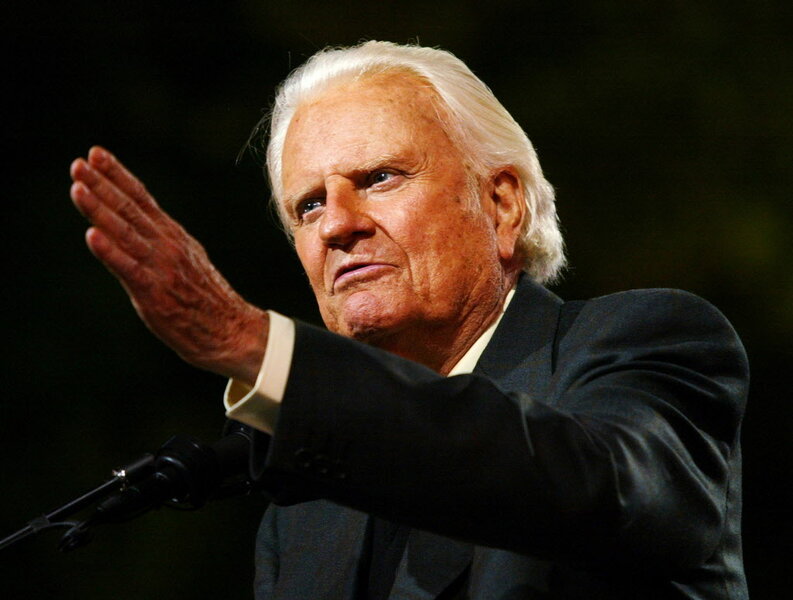

Billy Graham: a counselor of presidents who eschewed politics

Loading...

In 1957, when celebrity evangelist Billy Graham was gearing up for four months of nightly revival meetings at New York’s Madison Square Garden, his fellow conservative Christians warned he was playing with fire – and not in a good way.

Fundamentalists said he was making a mistake by partnering with liberal New York Protestants, who in their view would corrupt the crusade. But Graham didn’t listen. He teamed up with a diverse coalition and preached the gospel to 2.4 million.

“Graham’s view was that if people wanted to help promote the revivals… then find ways to bridge theological differences,” said Barry Hankins, a Baylor University historian and author of “American Evangelicals: A Contemporary History of a Mainstream Religious Movement.” “That became a sort of metaphor for his whole life. He was willing to have an irenic spirit toward people whom he disagreed with. He really wanted to exude the love of Christ more than the theological judgment.”

With the passing of Billy Graham, the world lost a towering figure in Christianity’s 2,000-year history. In the pantheon of evangelists from the Apostle Paul to Billy Sunday, no one preached the gospel to more souls than Graham, who used stadiums and mass media as no one before or since.

He built on a rare combination of assets, from rugged looks to an earnest manner, a morally upright lifestyle and gift for plainspoken public speaking. Yet it was his willingness to befriend former foes, and irk some former friends in the process, that earned him an unprecedented global stage.

In an era when irascible fundamentalists held to the fringes of public life, Graham rose above his roots in that tradition and became the kinder, gentler face of evangelicalism. He was widely loved. Every year from 1956 to 2006, he ranked in Gallup surveys among the 10 most-admired men in the world. Presidents adored him as much as the general public did. As an adviser to presidents from Harry S. Truman to George W. Bush, Graham goes down as the Lincoln Bedroom’s most frequent occupant, according to Grant Wacker, a Duke University historian and author of, “America's Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation.”

“Beforehand, conservative Protestants didn’t have anything to do with [liberal] Protestants or Catholics, but Graham was willing to work with them,” said Larry Eskridge, associate director of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College. “That really served as a lightning rod in a lot of ways because he did get a lot of critique from the theological right and fundamentalist sectors who said, ‘What are you doing?’ ”

Admired though he was in many corners, Graham was also scorned, especially in circles that felt he shirked incumbent responsibilities. He disappointed theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who said Graham “neglected the social dimensions of the gospel” by avoiding pressing issues of the day. His 1982 visit to the Soviet Union, where he urged nuclear disarmament, led conservative columnist George Will to label him “America’s most embarrassing export.” Fundamentalist Bob Jones once called him the leading threat to Christianity.

But none of that hampered Graham’s rise to extraordinary influence.

Born in 1918 on a western North Carolina dairy farm, Graham came of age in a time of rigid social stratification. Whites and African-Americans used separate facilities. Fundamentalists dared not mix with people of different faiths. Graham largely reflected the era’s norms. He kept the races separate at revival events into the early 1950s and urged leaders to go slow on civil rights, according to Wacker.

But by his mid-30s, he was showing passion for crossing boundaries for higher purposes, even when authorities frowned. At a Chattanooga revival in 1953, he broke the law by removing ropes erected to keep white and black Americans separate. The following year, he permanently banished the ropes from his events.

Over the next three decades, Graham would lead hundreds of crusade events in foreign countries. He aimed to win converts and promote church attendance, even in non-Christian countries. One secret to his ability to get invited again and again was his refusal to speak ill of other belief systems, a practice that galled fundamentalists back in the United States.

“He would say, ‘I’m here to talk about Jesus’,” not to cast aspersions upon other belief systems, Wacker said.

Eager for any opportunity to share his message, Graham was the first Evangelist to make broad use of television. After a California revival catapulted him to prominence in 1949, he became player on the evangelical stage. He was instrumental in founding Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif., where efforts to bridge evangelicalism and the broader culture remain a priority.

Across his remarkable career, Graham’s priority was always evangelism – that is, leading individuals to accept Jesus Christ as lord and savior. When he had regrets, he pointed to moments when other concerns interfered with tearing down barriers and building up a kingdom of born-again believers. Example: having defended President Richard Nixon before he resigned in disgrace, Graham sought to distance himself from politics, even though he continued to play a pastoral role with presidents.

“You really get the sense that he believed he had been used” by Nixon, Eskridge said. “He begins to pull back from any overt political involvement…. He was never involved in the religious right or the Moral Majority. He had bigger fish to fry, in his mind, and felt that getting involved in politics hurt his attempt to get the message out.”

After taped conversations with then-President Nixon became public, including anti-Semitic remarks from Graham, the Evangelist begged forgiveness from Jews. Having built up much good will over many years, Wacker said, Graham largely received forgiveness from the American Jewish community.

In leading thousands to faith, Graham effectively revived revivalism, an American tradition of using outdoor preaching, music, and other effects to bring about heartfelt conversions. Pioneered by George Whitefield in the 1730s and sustained later by the likes of D.L. Moody and Billy Sunday, revivalism was thought to be fading by the 1920s. But Graham tapped into the tradition and brought it up to date, using everything from radio to stadiums for a higher cause.

After 1981, Graham’s peacemaking demeanor shared the spotlight with a more combative style of evangelicalism, one embodied by such culture warrior broadcasters as Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Tendencies toward infighting and suspicion of outsiders – defining elements of conservative Protestantism in Graham’s early days – resurged somewhat in the vacuum created by Graham’s gradual retirement. Even Graham’s son, Franklin, has diverged from his father’s nonjudgmental approach to other faiths, as the younger Graham has called Islam “an evil religion.”

Looking back on Graham’s life and career, scholars now see a rare historical figure who brought together a radical mix of old-time religion and modern sensibilities. Charisma surely helped, as did deep faith in a God whose redemptive work is not yet finished. What’s more, being a breaker of boundaries and friend of the scorned certainly didn’t hurt his stature in the legacy of Christendom.