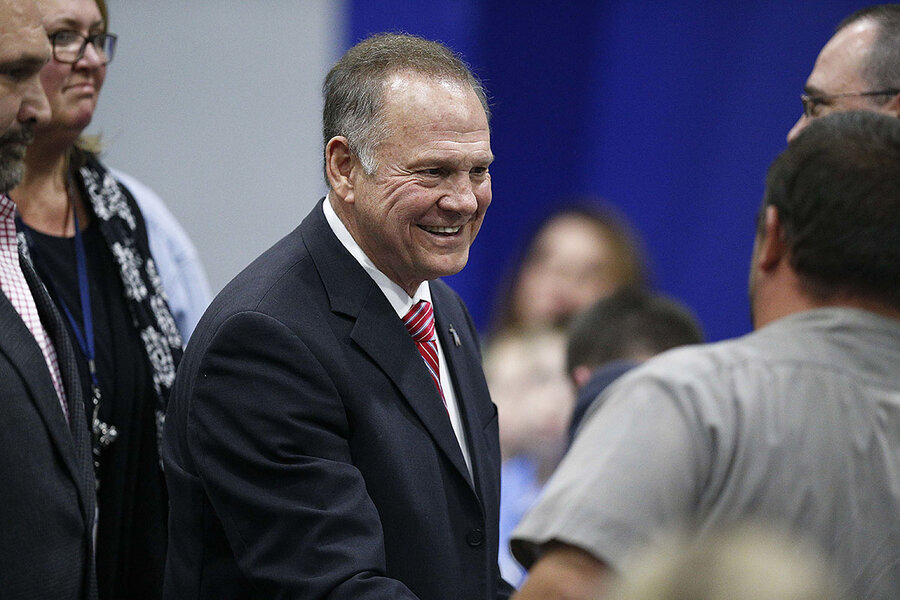

Behind religious defense of Roy Moore, an aggressive view of masculinity

Loading...

| New York

When some of Roy Moore’s defenders seemed to justify the idea of older Christian men dating teenage girls, a number of conservative Evangelical Christians, like a number of Americans, were both outraged and appalled.

The embattled Republican nominee for Alabama’s US Senate seat conceded Friday that he “dated a lot of young ladies” 40 years or so ago when he was in his 30s. He added, however, that he doesn’t “remember ever dating any girl without the permission of her mother.”

One of Mr. Moore's defenders compared a grown man dating a teen as akin to the biblical Mary and Joseph. While their ages are not given in the Bible, in some evangelical circles they are believed to be an adult male carpenter and young teenage girl. “There’s just nothing immoral or illegal here,” said Alabama State Auditor Jim Zeigler, defending the notorious former state chief justice’s alleged dates and assault of girls as young as 14. “Maybe just a little unusual.”

The accusations, and the justifications coming from some quarters, have roiled the ranks of many Evangelicals, and the condemnations have been in most cases unequivocal.

Yet such relationships, in fact, may not be as unusual among a certain subsection of American Evangelicalism as people think, a number of scholars and child abuse advocates say. Today, for some supporters of Moore, that deeply ingrained culture of Christian masculinity – or “biblical manhood” – can even justify the idea that adult-teen relationships are not immoral. (Legality is another question: Alabama's age of consent is 16.)

“I think these moments, both around [President] Trump and Roy Moore, are so revealing,” says Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a professor of history at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich., referencing the 11 women who accused Mr. Trump of sexual harassment before the 2016 election. On Friday, when asked for an official White House position on the matter, press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders told reporters that all the women are lying.

Most of the evangelical critics of Moore, on the one hand, have been well-known Never-Trumpers. Nevertheless, the president’s most ardent supporters still come from white Evangelical quarters.

“So a larger swath than I think most people expected don’t seem to want to condemn Moore’s past relationships, or critique that,” continues Professor Du Mez, a professor of religion and gender who has traced evangelical ideas of masculinity. “That’s what is really fascinating to me.”

On Wednesday, an attorney for Moore vigorously denied the allegations against him in a press conference.

Child marriage remains more common in the US than many people think. About 5 in every 1,000 15 to 17 year olds in the United States are married, according to the Pew Research Center, with child marriage more common in the South.

Over the past few days, dozens of men and women have recounted a dynamic in which older Evangelical men have often pursued, or have even been pursued, by young teenage girls.

And many described, too, a vision of gender roles in which young girls are at their most malleable and vulnerable, while older Christian men are understood to be their protectors and providers.

“Roy Moore is a symptom of a larger problem in conservative fundamentalist and evangelical circles,” tweeted Kathryn Brightbill, legislative policy analyst at the Coalition for Responsible Home Education, which advocates for home-schooled children. “It's not a Southern problem, it's a fundamentalist problem. Girls who are 14 are seen as potential relationship material.”

The reasons for this are complex, scholars say, but over the past few decades, many Evangelicals have asserted a more muscular understanding of Christian masculinity, one that affirmed traditional '50s-era gender roles – but in a much more militant and aggressive way.

And in many ways, masculinity and male potency is understood as a kind of God-given and difficult to control force. “This is what makes men, there’s a kind of wildness to masculinity,” says Du Mez, citing her research. “You cannot tame masculinity. Testosterone is God’s gift to men – and to women as well, they would say – but you can’t really control it.”

Conversely, women are seen as naturally seductive. Young girls are taught that it is a sin, in fact, to cause a man to sin by dressing provocatively or inciting male lust.

Rise of 'biblical manhood'

As Evangelicals came into their own politically in the 1970s, “they did so in a way that really set them apart from the rest of the country,” says Du Mez. “They really set out in a different direction.”

With the sexual revolution of the 1960s, the rise of feminism, and the legalization of abortion, many conservative Evangelicals began to emphasize a particular theology of “biblical manhood” and “male headship.”

The Vietnam War, too, only amplified Evangelical calls for an almost militaristic Christianity, even as they emerged as one of the most potent political forces in the Republican Party.

Popular evangelical books on family values, written and promoted by “Focus on the Family” founder James Dobson, became bestsellers. Couching arguments for traditional gender roles as determined “biochemically, anatomically, and emotionally,” Mr. Dobson wrote in his 1980 book, “Straight Talk to Men and their Wives,” he claimed that feminism was altering the “time-honored roles of protector and protected.”

In the 2001 book "Wild at Heart," still one of the most influential and popular Evangelical books on family values, the author John Eldredge famously wrote that God created men to long for “a battle to fight, an adventure to live, and a beauty to rescue.”

The role of women was conversely passive: they yearned to be fought for. And while they, too, possessed something “wild at heart,” it was “feminine to the core, more seductive than fierce.”

“Patriarchal authority is much easier to come by if there’s a big age difference,” says Du Mez. “Men have the obligation to provide and to protect, and with two 20-year-olds, it’s hard to achieve that differential.

“Whereas, if you have a 35-year-old-man and a 16-year-old girl, he’s probably already able to provide, and to assert that headship authority – it’s easier ... according the rhetoric I’ve been seeing within this particular Evangelical subculture.”

Echoes of this view of masculinity can be seen in other instances, such as “Duck Dynasty,” one of whose stars advocated dating teens. Last December, Edgar Welch, the gunman who was charged with firing a gun inside a Washington-area pizzeria that was the subject of an online conspiracy theory claiming it was a child sex ring, told investigators that “Wild at Heart” was one of his favorite books, even as he saw himself as a kind of protector hero for young women.

It’s a masculinity, too, that many prominent Evangelicals have cited in their support for Trump. “I want the meanest, toughest, son-of-a-you-know-what I can find in that role, and I think that’s where many evangelicals are,” explained the Rev. Robert Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas and outspoken Trump supporter.

A shift in thought on personal immorality in politicians

The acceptance of leaders like Trump and Moore also reflects a startling shift in attitudes among many Evangelicals. In a recent study by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), Americans in general have become more tolerant of elected officials who commit an immoral act in their private life, but are able to still behave ethically in public.

This has been especially the case among Evangelicals. In 2011, only 30 percent believed that personal immorality did not interfere with governing ethically. In 2016, 72 percent of white evangelicals reported that immoral leaders could still govern ethically.

Ms. Brightbill, the advocate at the Coalition for Responsible Home Education, and many others describe how ideas of “early courtship” allowed men to take over from the headship of a young girl’s father, shaping and molding a young girl’s role as a “helpmate.”

“The evangelical world is overdue for a reckoning. Women raised in evangelicalism and fundamentalism have for years discussed the normalization of child sexual abuse,” she wrote in a column in the Los Angeles Times. “We’ve told our stories on social media and on our blogs and various online platforms, but until the Roy Moore story broke, mainstream American society barely paid attention. Everyone assumed this was an isolated, fringe issue. It isn’t.”