Teen suicide: Prevention is contagious, too.

Loading...

| Mayville, N.Y.

Every day, 10th-grader Bridgett Marsh takes a look at her growing list of "reasons to live." Posted right next to her bed, it's a colorful jumble of names – family, teachers, friends, her cats – and some "really small things, but they matter a lot," she says. "The smell of campfire smoke ... party hats ... climbing trees."

She began writing the list during a five-day stay at a mental-health facility. With the stress of school starting in September last year, the depression she had been feeling got worse, Bridgett says, and she was thinking about suicide. That's when she chose hospitalization.

Since then, she's gotten better, and she continues to see a psychologist monthly. She plays guitar. She writes poetry. She adds to her list a few times a week. With her asymmetrical haircut and bubbly laughter, Bridgett is a typical teenager. What's not typical is how openly she talks about her struggles.

"I've learned how sad it is that people have to hide it, and I don't want to be one of those people," Bridgett says. "Starting talking to one person helps, and the further you talk, the better it gets.... It doesn't embarrass me."

TEST YOURSELF: Do you have a clue about actual teen behavior?

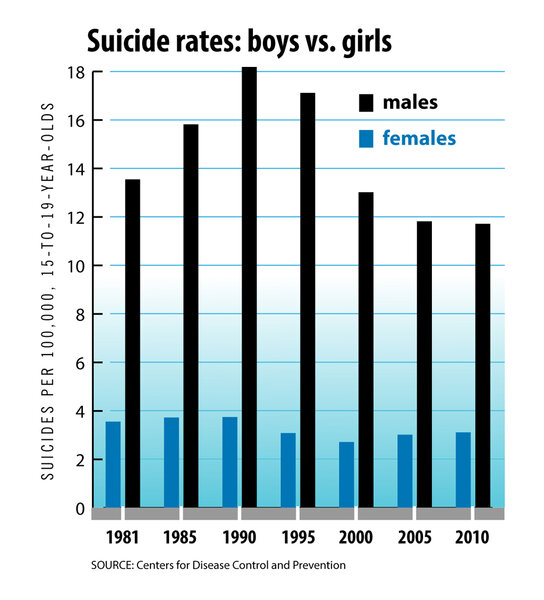

Behind every headline about teen suicide, there's a family tragedy and an even wider ripple effect. Between 1950 and 1990, the teen suicide rate in the United States nearly quadrupled. It declined somewhat through the early 2000s, but it has since plateaued and remains about triple the rate of 1950. For every death, research suggests that many more teens think about or attempt suicide, often in secret.

But the stories of lives saved often don't make headlines – and prevention experts are encouraged about progress in that direction. People like Bridgett are breaking down the taboo. Research is leading to better ways of recognizing teens in distress and connecting them with help. A clearer picture of how suicide "contagion" can happen is emerging – and prompting stronger efforts to guard against it.

Compared with 10 years ago, the proliferation of prevention efforts among young people represents "a quantum leap forward," says Ann Haas, senior director of education and prevention at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention in New York.

But it's difficult to prove if these bring down suicide rates, she says, and "while we're working in one direction, all of a sudden something else pops up."

The prominence of the Internet, for instance, Ms. Haas adds, "where kids can get exposed to the suicidal behavior of others half a world away," was not an issue 20 years ago. "[And] we're struggling to figure out how you contain that."

One reason to be "upbeat," Haas says, is that increasingly, prevention is happening "upstream" – developing in young people more of the resilience and coping skills that keep them from reaching a crisis point.

That trend is evident here at Chautauqua Lake Central School, where Bridgett is part of a group of students and adults well prepared to respond to teens on the edge – and better yet, pick up on signs that they might be heading that direction.

Trained through the Sources of Strength suicide prevention program, these teens find creative ways to spread the idea that by turning to key supports – such as friends, mentors, mental-health services, or spiritual outlets – everyone can get through his or her down days. They create a new norm that breaks through typical teen "codes of silence" and turns more students to "trusted adults" if they or their friends are in trouble.

Three girls have told Bridgett she helped save them. One, because "I've always been there for her, no matter what," she says. Another had an eating disorder, and thought she wouldn't have survived "if it hadn't been for me saying something to an adult." And one literally said, " 'You saved my life,' 'cause I took her to guidance one day [at school] and I guess it had a big impact on her."

Because adolescents tend to be highly influenced by peers, suicide contagion has been a longstanding concern. Being exposed to a suicide directly, or indirectly through news or social media, can increase their risk of attempting suicide, researchers say.

By age 17, roughly 1 out of 4 students is aware of a schoolmate who has died by suicide, according to a major new contagion study out of Canada.

Rather than seeing it as a taboo subject, prevention experts say, parents and school staff need to be better equipped to talk with young people about suicide – and to listen. Bringing it up in a constructive conversation will not plant the idea in kids' minds, they say.

There's a growing understanding about both risk factors and protective factors – and one of the strongest protections against youth suicide is connection with a trusted adult.

"It isn't just the negative stuff that is contagious," says Mark LoMurray, who created Sources of Strength in North Dakota after working in crisis intervention and attending 30 teen funerals in less than three years – 15 because of suicide.

But for hope and strength to spread, teens have to know where that resiliency comes from. Youth groups "could usually fire off the warning signs of suicide," Mr. LoMurray says, but when he asked how people get better if they are depressed, addicted, or traumatized, "most were giving a shoulder shrug."

That's when he started developing the colorful "wheel" depicting eight sources of strength that peer leaders focus on in their schoolwide messaging.

Sources of Strength is a comprehensive approach that influences the whole student population – one of several prevention strategies available to schools through dozens of research-based programs.

It's also part of the upstreaming trend. "Historically, suicide prevention has been very strongly focused on identifying individuals who are suicidal or in some very-well-identified high-risk group, and seeing mental-health or substance-abuse services as the strategy for addressing needs.... It's really come out of a medical perspective," says Peter Wyman, a psychiatry professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine who has studied various prevention efforts. Now, he says, there's an important shift toward "a greater recognition that reducing suicide rates is going to require a broader range of approaches ... to reduce the occurrence of distress ... and strengthen protective factors."

Suicide prevention strategies do make a dent

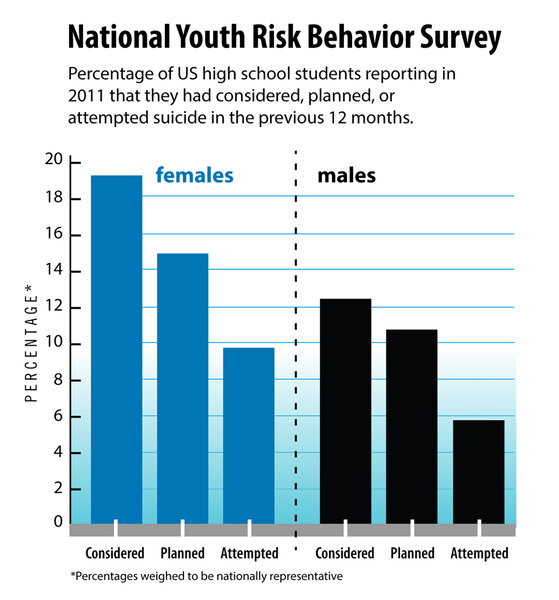

Nearly 16 percent of American high-schoolers who answered the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey said they had seriously considered suicide in the previous 12 months, and close to 8 percent had attempted it. More girls than boys think about, plan, and attempt suicide. But far more boys complete their attempts. (Boys tend to use means that are more immediately lethal, but it's not clear why, experts say.)

For 15-to-19-year-olds, suicide is the third most common cause of death. For native Americans ages 15 to 24, the suicide rates are about double the national average. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are at least twice as likely to attempt suicide, according to various studies.

A unique and complex mix of factors underlies each suicide. More than 90 percent of youth suicides have involved at least one major psychiatric disorder, most commonly depression. Among other common risk factors: a family history of suicidal behavior, substance abuse, parental mental-health problems or addiction, and stressful events such as romantic problems, abuse, divorce, and bullying.

Theories about why the rate increased through the 1980s range from more exposure to drugs and alcohol to broader availability of firearms, but there's no consensus.

The subsequent decline could have been caused in part by increased mental-health treatment, experts say. Crisis hot lines were also established, and in recent years they have been migrating online and to texting formats to keep up with teen habits. Students in some schools have been offered screenings and referrals. "Gatekeepers" such as teachers and youth leaders have been trained, though not universally (18 states require suicide-prevention training for school personnel). Access to lethal means has been reduced – through more secure storage of firearms, for instance.

Had such resources not been devoted to teen suicide prevention, the rate today could be much higher, says Madelyn Gould, a longtime youth-suicide researcher and professor of clinical epidemiology at Columbia University in New York. One can't know for sure because "you're not going to have a control group in an alternate universe," she says.

When a death becomes bigger than life

Lisa Schenke had a dress picked out for her son Tim's June 2008 graduation. In May, she wore it to his funeral.

Tim was a top student with a college scholarship in hand. He was a well-liked soccer player. But he was also depressed and tangled up with alcohol and drugs. He had undergone various treatments, and although he communicated very little with his parents in his later teen years, he had confided once to his mother that he wanted to die.

Ms. Schenke was deeply touched by the flowers, candles, T-shirts, and poems placed at the school and on the railroad tracks where Tim had stepped in front of a train. But after two more young men with ties to Tim's school, Manasquan High School in Monmouth County, N.J., died by suicide on train tracks within four months, "all the alarms really went off that this is becoming a contagion," she says.

Experts came in and explained that "the first two suicides might have been idealized," Schenke says, so from then on memorializing was kept to a minimum at the tracks, and police started watching out for vulnerable kids there.

It's problematic "if deaths are commemorated or memorialized in a way that the person's death becomes bigger than their life," says Maureen Underwood, clinical director of the Society for the Prevention of Teen Suicide (SPTS) in Freehold, N.J.

"I can remember seeing a suicide note from a 14-year-old girl saying, 'At least if I die they'll put a plaque up in the school hall with my name on it,' " Ms. Underwood says. That may seem "irrational," but the desire to be noticed can feed imitative behavior "for kids who are thinking about suicide and feel like their life isn't worth very much anyway."

SPTS's website offers guidelines for memorializing student deaths in ways that avoid contributing to contagion. Media guidelines have also been available for several decades, because research has shown that the way suicides are reported has an effect on contagion.

The contagion effect

When a student dies by suicide, the risk of contagion goes beyond just those who knew him or her personally.

Twelve- and 13-year-olds exposed to a schoolmate's suicide think about suicide at a rate approximately five times as high as peers who have not been exposed, and their attempt rates are affected at nearly the same level, according to a major study published this year in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. For 14-to-15-year-olds, those rates nearly triple, and for 16-to-17-year-olds, the rates roughly double. Even two years after a schoolmate's suicide, the rates remain elevated, though to a lesser degree.

Based on about 22,000 surveys of adolescents in Canada, the study controlled for various factors such as poverty and a history of mental illness. It was the first to look at contagion on such a broad scale, but other studies, including some in the US, have found significant effects from exposure to peer suicide.

The "dramatic" contagion effect is "relatively independent of other risk factors," says study coauthor Ian Colman, an epidemiology professor at the University of Ottawa. The one exception: a stronger effect for students who had experienced a major stressful event such as abuse or the death of a parent.

The new finding that students don't need to know someone personally to be at higher risk "is a bit counterintuitive," Professor Colman says. "It's quite natural for schools to focus on those who are closest to the student who has died, but schoolwide interventions might be [better]."

Contagion can rise to the level of a "cluster," when a higher-than-usual number of suicides occur in a local community or are linked together some other way, such as through social media. Clusters are most common among those ages 15 to 24, and account for as much as 5 percent of youth suicides, says Ms. Gould, the Columbia University professor, who is studying 50 clusters of suicides that took place in the US between 1988 and 1996.

Since the first three related suicides in 2008, Schenke's tightknit New Jersey community has endured at least seven more suicides linked to the cluster. But many prevention efforts have taken root as well, and Schenke believes they are having a strong effect.

For both parents and kids, "it's definitely become less taboo here to go to a counselor," Schenke says. "We had a lot of deaths.... But it could have been a lot worse, because we really do know of a lot of teens and young adults that were helped."

Schenke has been open about her family's story – from writing a letter to the local newspaper editor shortly after Tim died to her recent book, "Without Tim: A Son's Fall to Suicide, A Mother's Rise from Grief." She reassures young people that they are valued, and encourages parents to keep trying when they worry their teen is slipping away.

In return, she's heard about lives restored to a healthy balance. "One mom shared with me that her daughter was in senior year with Tim and things were not good – she had severe depression and was possibly suicidal," Schenke says, but Tim supported and encouraged her. "After Tim died, seeing what happened with our family, [the girl] kind of got the strength from his death to say, 'I don't want that to happen.' "

Scott Fritz, cofounder of SPTS, lost his 15-year-old daughter to suicide 10 years ago. He has since devoted himself to educating teachers and parents. The main message that he and Underwood convey to parents: Talk to your kids about suicide. If they say they've thought about it, instead of recoiling in shock, say to them, "Tell me more." Some parents have told him that heeding this advice helped save their child's life.

Warning signs of suicide range from talk about feeling hopeless or feeling like a burden to extreme mood swings, rage, and a spike in anxiety. SPTS offers a free online video, "Not My Kid" (to view, go to http://bit.ly/1afoRpa), with tips about how to recognize and address warning signs.

Developing the power of peer influence

It's a Thursday morning in October, and nearly a dozen pairs of students are standing on the Chautauqua Lake Central School stage in an otherwise empty auditorium, twisting, bending, and giggling as they try to unlock the loops of yarn linking them together.

The Sources of Strength training includes games to help peer leaders connect, and then open up as the conversation turns to more serious matters.

In a circle of folding chairs, they talk about common causes of stress (breakups, applying for college, peer pressure, rough times at home) and the many ways they find to cope: hugs from a favorite teacher, friendships, playing sports or an instrument ("When I play my cello, nothing else matters," one girl says. "It makes me feel like I'm whole").

LoMurray, casual in his gray Sources of Strength sweat shirt, puts the kids at ease and tells them again and again how powerfully they can influence their peers.

Generally, fewer than a third of teens who are considering suicide will communicate that information to an adult, Professor Wyman says.

By comparison, four months after training, Sources of Strength peer leaders – about 10 percent of students in participating schools – were significantly more likely than a control group to expect help and to be willing to seek help from adults for suicidal students. Positive effects along these lines were found in the rest of the school as well. Peer leaders were more likely to reject codes of silence – telling an adult about a friend even if asked to keep it secret. And they were more likely to have increased the number of adults they trusted.

Wyman co-wrote the randomized controlled study, which took place in 18 high schools in Georgia, New York, and North Dakota and earned Sources of Strength a place on the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices run by the US Department of Health and Human Services. His current study in 40 schools will measure the program's ability to reduce suicide attempts.

Not many youth-intervention programs have measured the effect on suicidal behavior. But one major exception shows the promise of the upstream approach: the Good Behavior Game (GBG). It improves classroom behavior by dividing students, ages 6 to 12, into teams that lose points or privileges if any one member breaks classroom rules. A study in 19 Baltimore public schools found a host of positive outcomes for participants, both in childhood and in early adulthood. As young adults, they thought about suicide at half the rate of their peers in a control group. Eleven percent of young men who had been in a GBG classroom reported suicidal thoughts in the follow-up survey, compared with 24 percent of the control group. For young women, the figures were 9 percent versus 19 percent. (The GBC study authors define "suicidal ideation" – or suicidal thoughts – as a spectrum of thinking starting with thinking about dying or wanting to die, to imagining oneself dead, to planning to kill oneself.)

Across North America, about 250 Sources of Strength teams are established in schools, colleges, and community groups, and the numbers are steadily growing.

Sources of Strength improves school climate broadly because the peer leaders are not just star students or the kids who join a lot of clubs, Wyman says. They're explicitly chosen to span the wide array of social groups.

Chautauqua Lake isn't very racially diverse, but the kids in today's training include computer enthusiasts, athletes, Boy Scouts, musicians, members of the honor society, a Japanese exchange student, a teen mom, and a girl whose father is in and out of jail. Adviser Steve Johnston, a science teacher, says he originally questioned whether it would work to bring together such a cross section of kids. "But they really hit it off from Day 1," he says. Other students "observe these kids and they realize they're all getting along, so it just branches out ... and it creates a good deal of empathy."

When it comes to talking about suicide, "the taboo has kind of started to fade away," says Steven Akin, a senior who has been with the group since the first training two years ago. "If somebody were to come to me before..., I would have been like, 'Whoa, that's heavy stuff, I don't know what to tell you.' But now I feel a little bit more equipped to help."

TEST YOURSELF: Do you have a clue about actual teen behavior?

Both kids and teachers are reporting more concerns about students. "Our teachers are more aware now of how important their role is..., to be there to listen," says Principal Joshua Liddell, who oversees about 600 students in Grades 7 to 12.

Having "students down in the trenches ... decreases the likelihood that kids are going to slip through cracks," says school counselor Jason Richardson.

When students have reached out to Mr. Johnston for themselves or a friend, "it's always gotten better; it's just getting through that low point," he says.

In the past two years, the peer group has conducted a "random acts of kindness" campaign, mentored elementary students, tackled bullying, and put up posters showing students with their "trusted adults." This year, they are considering hosting small-group discussions throughout the school to address suicide risks and the preventive strengths.

"In school there's not that much time to talk to each other," Bridgett says. "If we reach out to more people, they'll be able to open up, too, hopefully, and they'll feel safe to do that."