With eye on midterms, unions push to win back Trump's blue-collar voters

Loading...

| Washington and York, Pa.

Nancy Stough’s vision for a strong American economy harks back to her girlhood. Her father, a union shop steward working at American Chain & Cable, sometimes went on strike with fellow workers to push for better pay and benefits.

“They rallied around” and stood shoulder to shoulder, she recalls. “People would make kettles of soup, that kind of thing, until the strike was over.” A working-class prosperity took root here in her hometown of York, Pa.

Now Ms. Stough, a retired union member in her own right with a solid pension from Harley-Davidson alongside her Social Security, is active with her machinists’ union, promoting the idea of worker empowerment for the next generation of American workers.

Why We Wrote This

In decline for decades, the US labor movement is making a major effort to woo blue-collar voters they lost to Trump in 2016. Labor leaders believe they have the political momentum, but it will be an uphill fight.

It’s an uphill fight, especially in the age of Donald Trump. He won legions of working-class voters with an “America First” trade policy, yet refused to sign on more broadly to what unions view as a pro-worker agenda. The coming midterm elections this fall, with control of Congress at stake, represent a major test of whether organized labor can reclaim its hold on the blue-collar vote and help shape new economic policies for America.

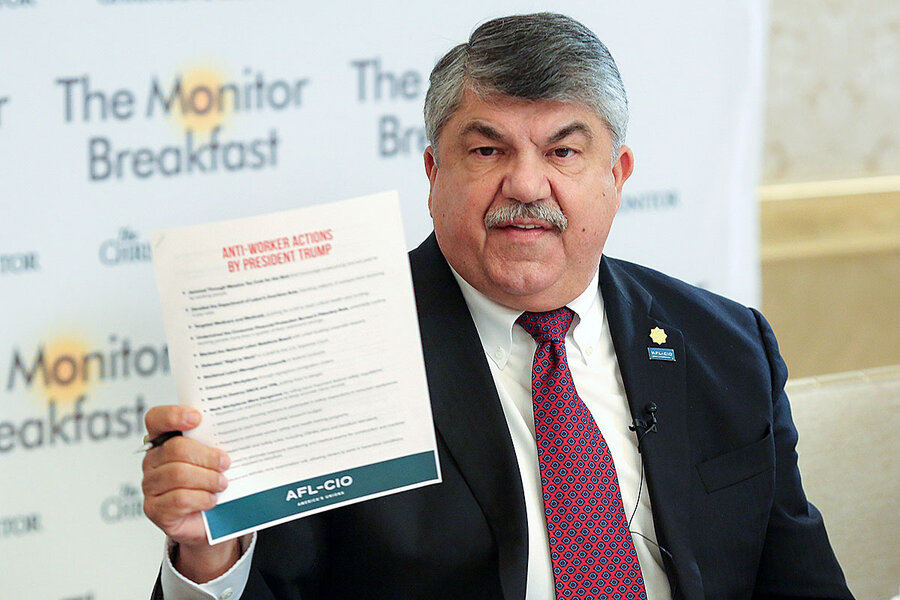

“It’s not true that in rural districts you have to be conservative, or in the middle of the road,” Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, told news reporters Wednesday at a Washington breakfast hosted by The Christian Science Monitor. He said that in Pennsylvania’s suburban/rural 18th District, “Conor Lamb spoke of our issues. He spoke of collective bargaining, he spoke of joining a union, he spoke of protecting Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid. And he got elected in a district that was computer-designed so that no Democrat could ever win. A computer said no Democrat could ever win this district, and he did.”

From Mr. Trumka to rank-and-file loyalists like Stough, many union voters are fired up and confident they can influence not just the midterm elections but also issues like the “fight for $15” on minimum-wage laws.

And even while feeling embattled politically in the Trump era, they are forging ahead on organizing new workplaces in places like the newsroom of the Chicago Tribune. The number of union workers in the US has risen from a recent low of 14.4 million in 2012 to 14.8 million in 2017.

Public support has also edged up. In a Gallup poll last year, 61 percent of Americans said they “approve” of labor unions, up from 56 percent in 2016 and similar to levels seen when the question was asked in the 1990s and as far back as 1941.

A blip or a rebound?

It is too early to say a turnaround is under way. Unions also saw rising membership during the booms of the late 1990s and mid-2000s but couldn’t sustain the momentum when recession hit. The share of workers represented by unions is nearly half what it was in 1983, in part because of the economy’s shift away from factory jobs, and in part because of state and federal policies that have made it harder to organize in new workplaces.

But what’s clear is that unions aren’t accepting decline as inevitable, and experts see their efforts as having significant political and economic stakes.

“Make no mistake about it, organized labor understands how crucial it is to get out the vote,” says Terry Madonna, a political analyst at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa. “It's a crucial element for the Democrats ... to reach out to their working-class voters, voters that they lost in 2016.”

A Quinnipiac University poll recently found a drop in support for Trump among white voters who don’t have college degrees. While 49 percent say they approve of the president, 47 percent in the July poll said they disapprove.

At the Monitor Breakfast, Trumka voiced confidence in Democrats’ prospects and in labor’s influence. But partly that’s because unions aren’t taking members’ support of union-endorsed candidates for granted.

“This is going to be the biggest, deepest member-to-member program that we’ve ever had. And I think deepest, because it’s going to go down past House members into state races, state Senate, and state House races.... Normally we start our door knocks and our phone banks after Labor Day weekend. We started the first of June this year.”

The candidates themselves have a role to play, he added.

“All of them, if they talk about kitchen table economics, if they talk about the issues that affect working people – their wages, their health care, their pensions, their schools – if they talk about those, they win,” Trumka said.

Pro-union agenda

Would a stronger labor movement mean a better economy for workers? Economists don’t all agree, but many see the decline of unions as an important factor behind relatively slow wage growth in recent years.

That’s the message unions are trying to sell in places like York, where factory jobs persist but no longer dominate like they once did. Manufacturing facilities dot the landscape along with farms surrounding a city of 44,000. A historic city core is flanked by neighborhoods of sometimes worse-for-the-wear residences.

By many measures, the economy here is strong. Unemployment of 4.1 percent essentially matches the national average.

But jobs that carry better pay and benefits could boost the whole economy, with the benefits more widely shared, says Tom Santone, who heads AFL-CIO activities in the York area. “You can’t have a strong economy if you’re leaving people behind.”

It’s an issue that resonates across Pennsylvania, where a bevy of competitive congressional races symbolize labor’s nationwide effort to flex its muscle.

“We have the density to have a real impact” on close-fought House races from York and suburban Philadelphia to the western part of the state where Mr. Lamb recently won the special election, says Rick Bloomingdale, president of the Pennsylvania AFL-CIO.

Trump is scheduled to visit Wilkes-Barre, Pa., Thursday, a former coal-mining center.

Trump’s assertive stand against China and other nations on trade has won support from workers who like the president’s call for fair, “reciprocal” trade relations after an era of offshoring factory work. His tariffs on steel imports have been praised by Trumka and other labor leaders.

But on a host of fronts Trump has rebuffed unions, from a tax-cut plan favoring corporations to moves by agencies including the National Labor Relations Board that undercut unions. Republicans are also moving against unions on the state and local level.

In Missouri, labor is leading the fight against the state’s decision to pass a right-to-work law, allowing workers who don’t join a union to avoid paying dues, even as they benefit from union bargaining over contracts.

“They listened to the whispers of a few right-wing, corporate billionaires,” Trumka said at the breakfast. “So, working people took matters into our own hands. We were tasked with getting 100,000 signatures to put the law to a statewide vote. You know what we did? We organized and turned in more than 300,000 signatures. The election is Tuesday.”

And he predicted: “Let me tell you something: We’re going to win.”

Staff writer Linda Feldmann contributed to this story from Washington.