What US-Canada border security looks like through the eyes of a Border Patrol agent

Loading...

| Swanton, Vt.

Driving along the Vermont-Quebec border, U.S. Border Patrol Agent Paul Allen keeps a watchful eye on passing cars. That maroon Toyota Tacoma is familiar. The blue Ford F-150, too. “If you’ve worked this area long enough, you know who should be here, who shouldn’t be here,” says the forest-green-clad agent.

Mr. Allen and other agents seek immigrants crossing illegally from Canada, working in woods and lakes along the longest land border in the world. He has apprehended “thousands” since joining the Border Patrol in 2008.

The 5,525-mile-long U.S.-Canada boundary has been overshadowed by an immigration debate that’s often focused on the U.S. border with Mexico. But this northern frontier catapulted into American awareness in recent months after President Donald Trump pointed to Canada as a source of illegal migration and fentanyl. The president cited those border grievances as a primary reason for imposing tariffs on Canada.

Why We Wrote This

The U.S.-Canada border has become contentious under President Donald Trump, who is pressing Canadians over immigration and drug flows. Border Patrol agents say their morale is up, yet community tension simmers.

In three months’ time, Mr. Trump’s aggressive and controversial actions on immigration have included crackdowns on both illegal and legal pathways into the country, along with court-challenged deportations to El Salvador. After declaring a national emergency and stationing troops along the southern border, that area saw Border Patrol encounters, a proxy for illegal crossings, fall 95% in March compared with that month in 2024.

The same plummet, by percent, was seen along this northern Swanton Sector, which spans parts of New Hampshire and New York, and all of Vermont. This location also experienced record crossings under the Biden presidency, although at a much smaller scale. In March 2024, there were 1,109 Border Patrol encounters here, compared with 54 this year – and that’s without the military standing sentinel as it is down south.

More is known about southern-border enforcement. In part, that’s because the government publishes certain immigrant processing data for the southern border but not for the north. American media have also paid more attention to the sheer volume of people arriving in the south, and the knock-on effects of their release into the interior, says Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, associate policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute.

Still, it’s not all quiet on the northern front. Facing tariff threats from the incoming Trump administration, the Canadian government in December committed to spending $1.3 billion more (Canadian; U.S.$900 million) on border security. Mr. Trump’s calls for the country to become the 51st U.S. state have roused Canadian patriotism and unsettled relations on both sides of the border.

On Tuesday, newly elected Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney and President Trump plan to meet in Washington, with a focus on trade and security.

A March drive with Mr. Allen is a window into how the northern border has changed under Mr. Trump’s policies – and the ripple effects on the communities that call this region home.

Activity along the border

Head out the window, Mr. Allen slows the car to a crawl. His eyes scan the gravel as he “sign cuts,” a specialized kind of tracking based on physical clues. He spots markers of a vehicle that tested out an illegal route. Agents’ eyes become trained this way over time.

In the rural Swanton Sector, where road signs warn of moose and snowmobiles, the Border Patrol relies on scattered sensors. He says it’s hard to detect footprints without fresh coats of snow. Dew helps, too. Cars can leave a more obvious trail, and some people will drive over railroad tracks. Mr. Allen, a leader at a station office here, says he’s stopped vehicles with babies on board and made arrests. Sometimes he can tell which direction they’ve gone from the way the gravel spun.

Smuggling of people and goods has vexed the U.S. Border Patrol throughout its century of existence. In 1925, the Monitor reported from Detroit that prices for “alien-smuggling” for migrants coming into America were “said to range from $30 to $50 for whites” and $150 to $200 for Asians. Unlike the Southwest’s extreme heat, temperatures up north can dip into negative degrees. That hazard made news in 2022, when a family from India froze to death on the way to Minnesota.

Locals like Owen MacCallum, an eighth-generation Quebec farmer, who live along the northern border, recall when the United States increased its border security in the wake of 9/11.

“All of a sudden, there was a greater fear of terrorist activities,” says Mr. MacCallum. He remembers as a child freely riding his bike around a block that dipped in and out of Vermont and Quebec.

During the first Trump term, a route in the Swanton Sector known as Roxham Road went viral as a popular spot for migrants trying to gain entry into Canada by way of the U.S. Under the Biden administration, Border Patrol encounters here swelled to record highs in the opposite direction. Encounters hit a peak of 3,310 last June, with 97 countries represented last fiscal year.

“I don’t even have other words than ‘completely overwhelmed,’” says Mr. Allen. “We use certain radio calls, you know – ‘1079,’ we’ll say. That’s ‘Nobody’s available.’”

Canadian immigration policy has a major effect on migrant flows on the U.S. side. Mexicans made up the largest number of those intercepted by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, until Canada placed new visa restrictions on Mexican visitors in early 2024. In the subsequent six months, illegal crossings by Mexican nationals seeking entry into the U.S. fell by 72% compared with the same period in 2023, the government said in January. Apprehensions of Indian nationals, many entering on visitor visas, rose last year, says an RCMP spokesperson; Canada tightened entry for temporary visitors like international students last fall.

During the Biden presidency, the Border Patrol here released unauthorized immigrants into the U.S. to await their initial immigration court dates, typically years away due to a backlog in that system. Sometimes agents resorted to calling a taxi to take them to their destination, says Mr. Allen, or drove them to a bus station themselves.

Illegal crossings began to fall during President Joe Biden’s last year in office after he received enforcement support from Mexico and limited asylum access. On his first day back in office, President Trump declared a national emergency at the southern border, but not the northern one. Neither was the military deployed up here. Now, unauthorized immigrants largely face detention instead of release by the Border Patrol, says Mr. Allen, whose sector is also leveraging fast-track deportations called expedited removal. (That data, however, isn’t published.)

Agents here say Mr. Trump’s crackdown has made would-be unauthorized immigrants far more hesitant about crossing. And that shift, agents say, has allowed them to actually do their jobs: delivering consequences to law-breakers without releasing them into the interior. Mr. Allen calls it a “morale booster.”

As crossings have dropped nationally, so have deaths involving fentanyl, which can be lethal in minuscule doses. While Mr. Trump has linked the northern border to fentanyl trafficking, the vast majority of those seizures by Customs and Border Protection are along the southern border – and at ports of entry there. (The Border Patrol only operates between ports.) The Swanton Sector seized less than half a pound of fentanyl last fiscal year.

Simmering community pressures

Even with illegal entries down, community tensions here have in some ways risen since the start of Mr. Trump’s final term.

On Jan. 20, Swanton Sector Border Patrol Agent David Maland was fatally shot at a traffic stop. One person has been indicted on federal weapons charges. In March, new border-security rules altered Canadians’ longstanding access to a library straddling the Vermont-Quebec border.

Cross-border collaboration doesn’t always make headlines. Last year, the Swanton Sector worked with Mr. MacCallum, the Quebec farmer, to install cement barriers along his property. They were meant to stop drivers from careening across who were wrecking his soybeans.

“That seemed to stop them,” says Mr. MacCallum, who also plans to dig a ditch for more deterrence. “I think we both respect each other, and just want to be good neighbors.”

Relationship-building is part of an agent’s job. Mr. Allen hands out magnets giving locals a number to call if they see any “suspicious activity.”

Locals serve as eyes and ears for the patrol, whose sector spans up to 100 miles into the interior. A tip last month quickly escalated.

On April 21, agents near Richford, Vermont, responded to a call from a “concerned citizen” who saw two people with backpacks entering farmland a couple of miles south of the border, according to a spokesperson for Customs and Border Protection. Border Patrol apprehended one, but the second fled. In a subsequent search, “Agents located and apprehended additional individuals determined to be illegally present in the United States,” on a dairy farm.

Customs and Border Protection, which includes the Border Patrol, denies that this incident was a raid targeting farmworkers, calling such claims “false” in an email.

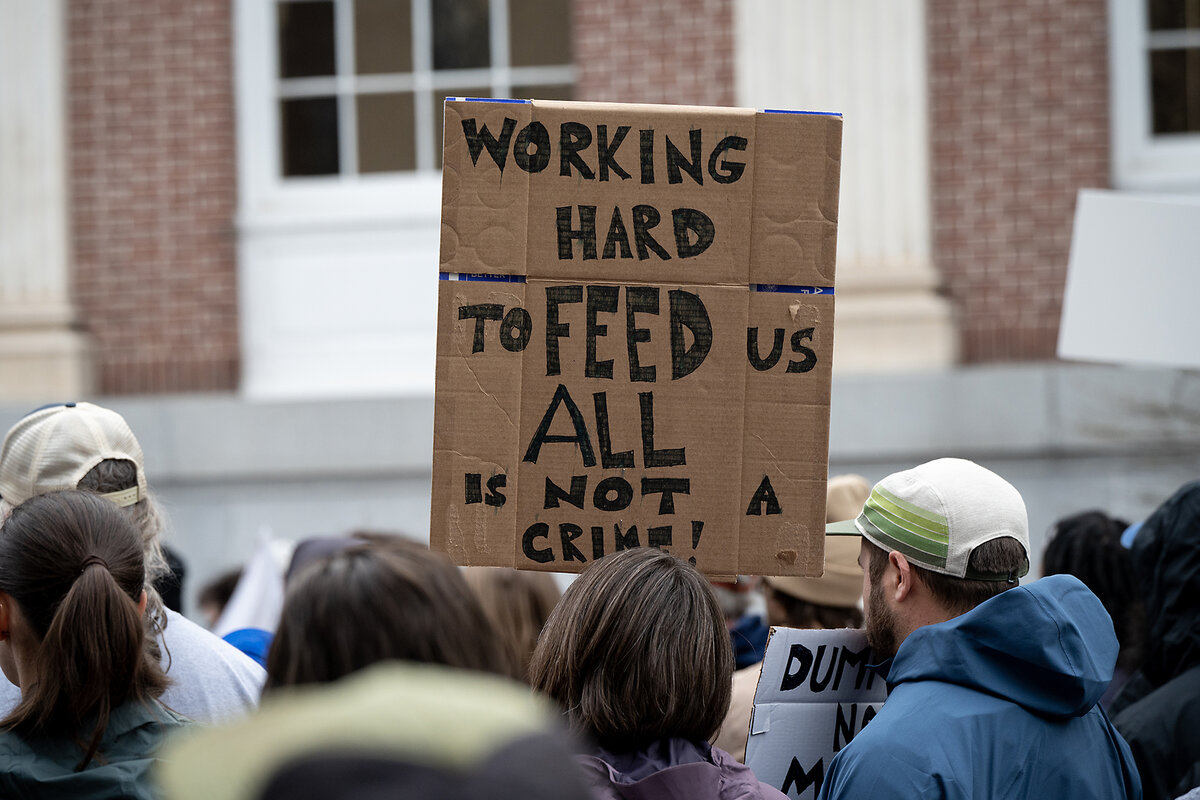

A Vermont immigrant advocacy group, Migrant Justice, is highlighting this recent detention of eight people as the largest immigrant arrest of farmworkers in recent state history. The group launched a petition urging release of the dairy workers on bond. One of them had been in asylum proceedings, says Migrant Justice, which held a solidarity rally last month.

“We work hard to support the economy of this state, working long hours for low wages, doing work that U.S. citizens don’t want to do,” said Cristian Santos, a member of the group’s Farmworker Coordinating Committee, in a statement. “We demand freedom for our fellow community members and won’t rest until they are free.”

A call for more agents

The Border Patrol has labor issues of its own. The agency has been offering hiring incentives – up to $30,000 – to attract new recruits.

“It’s a great time to get into Border Patrol,” a recruiter told a Vermont radio show in March. No prior military or law enforcement experience is required, he said, beyond one year of related work experience.

A wind blows down the border, twitching pale dry grass. Two forms approach from a distance. They walk down a clearing along the international boundary, pace clipped, nearing the car in sunglasses. They catch Mr. Allen’s eye.

“These aren’t illegals,” he concludes. More likely, they are locals getting exercise.

He says hi as they power-walk past. The agent drives on, leaving tracks of his own.

Staff writer Sara Miller Llana contributed reporting from Hemmingford, Quebec.