Wrong door, wrong driveway: How US got to shoot first, ask later

Loading...

| TYBEE ISLAND, GA.

A string of perplexing shootings across the United States has revealed an on-edge society where firing first and asking questions later – in other words, letting a gun do all the talking – has become, for some, acceptable if not always legal.

The incidents involve people, including children, who have been shot at for seemingly mundane acts and mistakes: ringing the wrong doorbell, pulling into the wrong driveway, chasing a ball into a neighbor’s yard.

There has long been a sense for travelers in unfamiliar areas that some driveways are better not breached – lest one meet a proverbial recluse holding a shotgun loaded with rock salt and nails.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA series of high-profile shootings for seemingly mundane things – ringing the wrong doorbell, turning into the wrong driveway – reveals an on-edge society. This does not take place in a vacuum.

Yet a barrage of state laws scrapping concealed carry permitting requirements, the replacement of a legal duty to retreat from danger with a “stand-your-ground” standard, and a steadily growing national arsenal of handguns and high-powered rifles have heightened the risk of violence. These trends have raised concerns about desensitizing society to the costs of firing a weapon too soon, and they represent changes to a core social contract about the role of guns in a democratic society.

“What we are seeing is an abdication of responsibility to the public – we are not concerned about our fellow man,” says Kenneth Nunn, an expert on U.S. self-defense law and a law professor emeritus at the University of Florida. “I think there’s a belief that if you’re a homeowner and have a gun, you’re basically insulated from any criminal charges if you use it ... that there’s no limiting principle for vigilante violence. And some people are OK with that.”

To be sure, arrests have been made in most of the cases that have generated headlines in recent weeks. But at the same time, gray areas in the fast-shifting legal landscape can make it difficult to fully know and understand the civilian rules of deadly force, which differ in small but important ways from those applied to police officers.

“Everybody is on edge”

That situation is amplified by the fact that about two dozen states have gotten rid of permitting for concealed carry. Since such permits have a training component, the result is less training for gun owners.

In addition, the Supreme Court ruled last year that authorities can’t arbitrarily deny Americans the right to carry a weapon. And although the right to bear arms is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, laws governing their use make up a state-by-state patchwork – and amount to a heap of contradictory regulations for a deadly tool.

This is all taking place against a backdrop of politically charged anxiety. Some 88% of gun owners say self-defense – not hunting or sport shooting – is the main reason for owning a weapon. That purchasing trend has been increasing.

“When I ask, why are you here [to get training], the response is usually, ‘I’m scared,’” says Georgia firearms trainer Rodney Smith. “Everybody is on edge. Somebody walks up and you think, ‘Oh, they’re coming out here to rob me.’ They’re overzealous in how they respond.”

Gun-buying spiked in the Obama era, saw a “Trump slump” in the late 2010s, and surged again during the pandemic. The U.S. now has about 400 million guns in circulation – more than one per resident.

Though the bulk of gun buyers have been those adding to their collections, the last two decades have also seen an expansion in the kinds of Americans who own guns. Data from Northeastern University and Harvard found that women as well as Black and Hispanic people made up significant shares of first-time gun buyers between 2019 and 2021.

The longing for a sense of safety is natural, but studies have shown fairly conclusively that more guns and laxer gun laws have not reduced crime, and have sometimes increased violence. These latest shootings are examples of that dynamic, says Robert Spitzer, author of “The Gun Dilemma.”

“Very typically, these are cases of people who are amateurs and who don’t have much in the way of training and experience and they lack judgment, which are problems that are escalated when you put a gun in a person’s hand,” says Dr. Spitzer, a professor of political science at the State University of New York at Cortland. “People say that an armed society is a polite society. That’s false. An armed society is a terrified society.”

Moving away from “duty to retreat”

Whereas two decades ago most Americans were under the legal “duty to retreat” from danger in public areas, 38 states have since shifted to the stand-your-ground standard, which makes no requirement that those who feel in danger must delay before responding to a threat with deadly force.

It is an expansion of the castle doctrine, which dates to English common law and holds that individuals have the right to use force to protect themselves in their own homes.

These provisions are by no means absolute. You can’t instigate a confrontation and then claim you fired in self-defense.

But resolving such shootings can be tough calls. Self-defense claims are notably difficult to parse, in large part because there’s often only one side of the story left to tell after someone is killed – the shooter’s declaration that they feared for their life.

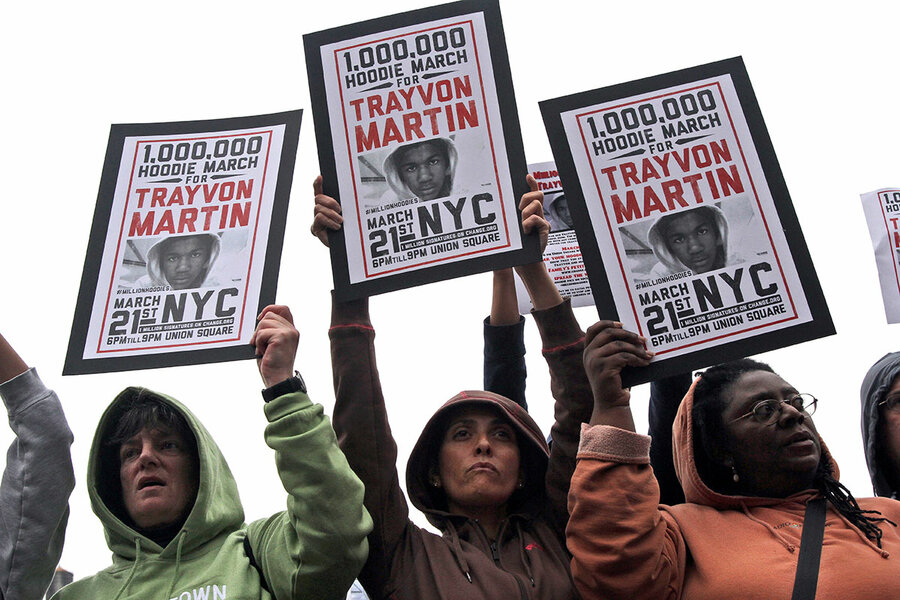

Still, juries have been fairly decisive in decoding stand-your-ground laws, even if prosecutors have been at times slow to press charges against shooters. In 2013, a Florida jury found a neighborhood watchman named George Zimmerman not guilty of murder for following, confronting, and then killing a Black teenager named Trayvon Martin, after Trayvon fought back. Around the same time, Jordan Davis, the son of current Rep. Lucy McBath of Georgia, was killed after an argument with a white man about loud music. The man, Michael Dunn, was sentenced to life without parole.

In 2019, another Florida jury found Michael Drejka guilty of killing Markeis McGlockton in another racially charged case that stemmed from an argument over a parking spot. And in early 2020, three white men followed a Black jogger named Ahmaud Arbery through a Brunswick, Georgia, suburb, killing him after Mr. Arbery tried to defend himself. The men claimed self-defense. A state jury found all three men guilty of murder.

This month in Texas, these issues have taken an interesting turn. Gov. Greg Abbott has injected the executive branch into the debate, vowing to grant clemency to an off-duty U.S. soldier whom a jury found guilty of murder for killing a social justice protester in 2020. The soldier had claimed he shot the protester, who was carrying a rifle, in self-defense.

Anything-goes culture

Such an interjection by the executive branch sends a powerful message to the public.

“I don’t have a problem with people using force and even deadly force to defend homes. The social problem ... with stand-your-ground is more endemic than the legal problem,” says Mr. Nunn, the self-defense law expert, who is Black. The problem is that “regardless of what the law says you have to do to claim stand-your-ground, the public and police and a fair number of prosecutors seem to believe that you don’t have to do those things that are necessary to claim self-defense. I think [such failures to act according to law] create a culture, and it’s a culture where people believe that as long as you are a white person using a gun, you can do whatever you want.”

A 2013 study that analyzed FBI data found that race plays a significant factor in so-called justifiable homicide rulings, and that this is even more pronounced in states with stand-your-ground laws.

In some ways, the recent headline-making shootings present an opportunity for states to step up training requirements, says Mr. Smith, the gun safety instructor.

While most gun owners are concerned about authorities prosecuting lawful gun owners who are defending themselves or innocent strangers, most also support that extensive training be required in permitting, polls indicate.

“Ability, opportunity, and jeopardy have to come together before deadly force can be used,” says Mr. Smith, founder of the Georgia Firearms and Security Training Academy in Monroe. “That case in Kansas City, the guy was knocking on the door. Was there ability to hurt the homeowner? No. Was there an opportunity to hurt him? No. The door was there. Was the man’s life in jeopardy? Hell, no. All these things have to come together for deadly force to be authorized. You are responsible for every round you put downrange. And every round you put downrange has a lawyer’s name on it.”

To him, incidents like that illustrate the range of legal pitfalls and unintended consequences that can come into play. He recounts the 2022 case of a bodega clerk in New York who was charged with murder after stabbing to death an assailant. The murder charge was dropped amid an outcry.

Mr. Smith also cites a case of a “good guy with a gun” at an Indiana mall last year. An armed young man saw another man firing indiscriminately with a rifle in the food court. He drew his own weapon and killed the shooter. He was widely hailed as a lifesaving hero. But Mr. Smith also sees the risks involved with a young gun owner taking a 40-yard shot with a pistol in a crowded area. “I don’t know if I would’ve tried that shot,” says Mr. Smith.

Historically, guns have been strictly regulated in the U.S. “People in the 1700s and 1800s and early 1900s well understood that when more average people have guns and are carrying them around, you get more bad outcomes,” says Dr. Spitzer, the sociologist. “But that lesson seems to have been lost in the last couple of decades.”