Chicago mayoral race spotlights cities’ post-pandemic struggles

Loading...

| Chicago

At campaign events across Chicago’s South and West sides, Democratic Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s supporters all drive home the same point: Don’t judge her on the past four years. Think, instead, about what she could do in the next four.

“You can’t change nothing in four years,” says local Alderman Emma Mitts to a cheering crowd in West Garfield Park, an area with the city’s highest homicide rate. “In a pandemic? Even being a sister?”

It’s an atypical message for an incumbent politician – but then, nothing was typical about Mayor Lightfoot’s first term. Less than one year after the former president of the Police Board triumphantly took office as Chicago’s first Black female mayor and becoming one of America’s most prominent LGBTQ leaders, COVID-19 brought life in her city to a screeching halt.

Why We Wrote This

Lori Lightfoot is the first pandemic-era mayor attempting to run for reelection in a major city. The campaign is a window into how Chicago has – and has not – rebounded from the COVID-19 crisis, with problems like crime now top of mind.

Ms. Lightfoot, like other mayors across the country, was on the pandemic’s front lines. She found herself managing mask mandates, school closures, and vaccine distribution, along with surging crime and mass protests against racism and police brutality. She engaged in high-profile fights with fellow Democrats in Springfield and powerful left-leaning unions, while also being attacked in conservative media.

Politically, almost no big-city mayor made it through those years unscathed. Former Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti’s approval rating dropped nearly 20 percentage points, while New York Mayor Bill de Blasio left office with a lower favorability rating among New Yorkers than former President Donald Trump. Term-limited Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney made news last summer when, after a July Fourth shooting, he said he’ll “be happy” when he’s not in charge anymore.

Ms. Lightfoot, with an unfavorability rating that’s more than double her favorability, is one of the few who’s trying to persuade her constituents to give her another term. As such, Tuesday’s vote may serve as an indicator of how well cities like hers are rebounding from the public health crisis – and whether politicians weighted down by that tumultuous time can have a second act. More broadly, the election is spotlighting a city grappling with a sense of urban decline, as Chicago, like many major cities, confronts partially empty downtowns and issues of public safety, policing, and race.

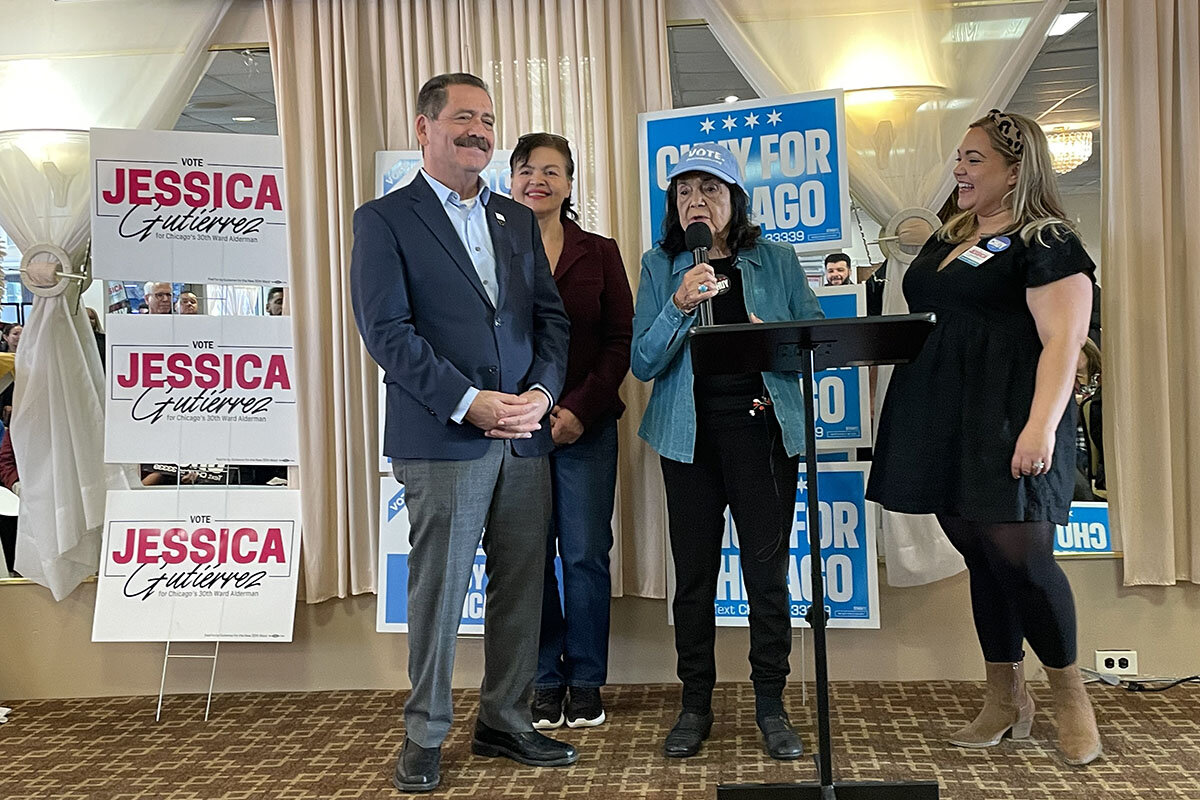

With nine candidates running – all of them Democrats – polls suggest the race is largely between four: Ms. Lightfoot; U.S. Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García, who represents part of the city; Paul Vallas, who served as Chicago’s budget director and CEO of Chicago Public Schools in the early 1990s; and Brandon Johnson, a Cook County commissioner and former teacher. Some analysts are bearish on Ms. Lightfoot’s chances of even making it to an April runoff election between the top two vote-getters if no candidate wins an outright majority.

“Of course, we made mistakes along the way,” Ms. Lightfoot says in an interview with the Monitor following the West Side event. “But we learned from those mistakes, and I think that’s made me a better leader.”

“When you take the certainty of people’s lives, and you upend those lives as we had to do during the course of the pandemic, that causes a lot of anxiety. And I think there’s still an undercurrent of that in the city,” says the mayor. “It’s absolutely informing people’s perceptions of, ‘Is the city going in the right direction or not?’”

Crime and public safety

To that question, almost three-fourths of Chicago voters answered no in a recent poll. While the health crisis itself has receded and life has gone back to normal in many ways, specific problems that flowed from the pandemic remain front and center.

Public transportation ridership rates are still far below what they were pre-pandemic, with many residents complaining of delays, dirty trains, and an unsafe environment. Enrollment in Chicago’s public schools, which saw three teacher strikes in the space of three school years, continues to fall.

At campaign events across the city, voters repeatedly cited public safety as their top concern. With homicides hitting a 25-year high in 2021 and carjackings and thefts up across the city, more citizens are now worried about crime than about criminal justice reform, the economy, education, immigration, and taxes – combined. Several companies have closed shops or offices in Chicago, citing crime as a driving factor.

“It’s a new level of desperation and hopelessness that, I think, is playing a big factor in the rise of crime,” says Representative García, one of Ms. Lightfoot’s opponents, in an interview. “It’s impacting all of our lives.”

Like other U.S. cities, Chicago saw mass protests over police brutality following the murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis in May 2020. Some of those protests turned violent, leading Ms. Lightfoot to impose a citywide curfew and ask the governor to call in the Illinois National Guard.

Still, critics say Ms. Lightfoot was too slow to act, enabling looting and damage to dozens of businesses. “When she let them riot a second time on Michigan Ave., I was done,” says Bill, a Chicago voter who declined to give his last name.

Just like the Democratic Party as a whole, Chicago’s mayoral candidates offer a range of policy solutions to address the crime problem. The fact that not one of them is talking about “defunding the police” speaks to how much voters’ priorities have changed over the past few years.

Mr. Johnson is emphasizing the need to fund more youth employment opportunities and mental health services. Ms. Lightfoot, Mr. García, and Mr. Vallas are all promising to hire more police officers and ensure that the department is fully funded.

Mr. Vallas, in particular, is running as a “pro-police” candidate.

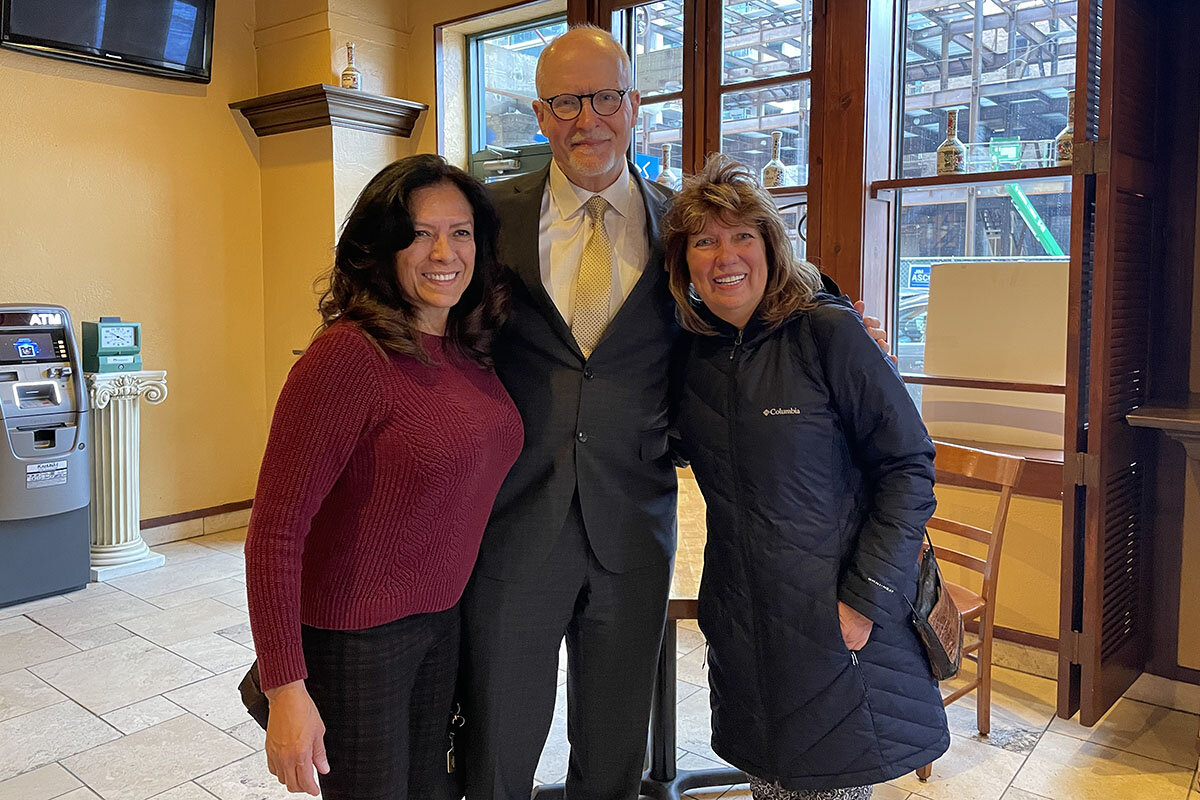

“After the George Floyd riots, [Ms. Lightfoot] literally destroys proactive policing. Suddenly the police are being restrained,” says Mr. Vallas, in an interview at a Greek restaurant that one voter characterizes as a “cop bar.”

“Public safety is the number one, two, and three problems,” Mr. Vallas continues, periodically pausing the conversation to shake hands with a voter or pose for a photo. “Lori Lightfoot inherited a lot of problems ... but I think that bad decisions made things worse.”

Fights with unions

Several voters here agree that Ms. Lightfoot was dealt a “bad hand,” but then made it worse.

“It showed the quality of her leadership,” says Jennifer Frei, a consultant attending a Vallas campaign event at a bar in Logan Square with her husband, Gerald Wilk, a retired carpenter. The two haven’t decided which candidate to vote for, but they aren’t eager for a second Lightfoot term.

“She just won’t be able to get anything done,” says Ms. Frei, referring to Ms. Lightfoot’s lack of allies in the city.

Since taking office, the mayor and former prosecutor has found herself at odds with Illinois’ Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker as well as fellow Democrats in the City Council. She’s had high-profile disputes with the Fraternal Order of Police, which has endorsed Mr. Vallas, as well as the Chicago Teachers Union, which has endorsed Mr. Johnson.

Both unions sparred with Ms. Lightfoot over COVID-19-related issues, with the FOP opposing a vaccine mandate and the CTU striking in 2021 and 2022 for more COVID-19 protections. The relationship between Ms. Lightfoot and the city’s teachers has been particularly acrimonious, with the mayor accusing the teachers of holding the city’s children “hostage” with their work stoppages and the leader of the teachers union saying Ms. Lightfoot was on “a one-woman kamikaze mission to destroy our public schools.”

Some say the disputes had less to do with the pandemic and more to do with Ms. Lightfoot’s aggressive personal style.

“I’m not so sure how much [the pandemic] had to do with her troubles,” says John Mark Hansen, a political scientist at the University of Chicago. “She’s had a very, very difficult time with the City Council. She’s had a couple of floor leaders quit on her – and that never happens. People who were strong allies of her, who said, ‘I’ve had enough.’”

Supporters contend that Ms. Lightfoot, as a Black, openly gay woman, faces a double standard. Chicago, after all, has a long tradition of brash mayors – including Richard J. Daley, who ran the city for two decades and was dubbed “the last of the big city bosses,” and Rahm Emanuel, the famously foul-mouthed former chief of staff to President Barack Obama, who had his own conflicts with the teachers union.

“When [Mr. Emanuel] cursed out CTU, no one said anything,” says Monica Faith Stewart as she leaves a campaign event for Ms. Lightfoot on Chicago’s South Side. “They just expect women to eat tea and crumpets.”

Michael Mayden, walking out with half a dozen “Lori Lightfoot for Chicago” yard signs tucked under his arm, nods his head in agreement.

“The pandemic hasn’t changed the role of the mayor, but it made the media stereotype her,” says Mr. Mayden. “They’re biased against a Black woman leading this city.”

But Mr. Johnson, in an interview at a pastry shop in Wicker Park, says it’s too late to repair the damage.

“If the mayor had one challenge, people might have mercy on her,” says Mr. Johnson. But “she’s had multiple tussles. I don’t know if there is anyone that she gets along with.”

Racial politics

In the final weeks of the race, Ms. Lightfoot has focused many of her attacks on Mr. Johnson, who has picked up millions of dollars in donations from the teachers union and others. In a city that is both highly diverse and highly segregated, Ms. Lightfoot has leaned into identity politics, bluntly telling Black constituents that a vote for Mr. Johnson, who is also Black, would likely only serve to elevate a non-Black candidate.

“Any vote coming out of the South Side for somebody not named Lightfoot is a vote for Chuy García or Paul Vallas,” said Ms. Lightfoot at a recent event. She added that Black voters who didn’t support her should “stay home” and not vote, a comment she later walked back.

Critics accuse Ms. Lightfoot of being racially divisive. In 2021, she made waves when she announced that she would only grant interviews to reporters of color, describing the Chicago press corps as “overwhelmingly white” – a stance that drew a lawsuit from a conservative group.

But racial politics are shaping other campaigns as well. Waiting for Mr. García to speak at an event in Belmont Cragin, an almost 80% Hispanic neighborhood, Maria Reyes, a preschool director who lives in the area, says she’s supporting Mr. García because “as Latinos, we want to support him.”

Ms. Reyes adds that she would like to see “equal opportunities for everyone – not just the South Side.” The comment is a reference to Ms. Lightfoot’s Invest South/West development initiative, which brought at least $2.2 billion to the city’s historically Black neighborhoods.

Ms. Lightfoot repeatedly highlights that initiative in her campaign stops in these two areas, where Ms. Mitts and other supporters encourage Black voters “to show up like never before.”

As dozens of supporters filter out of the hall, the campaign blasts Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” over a speaker – a song the chart-topping star wrote to “celebrate our survival, and celebrate how far we’ve come” over the past few years.

Reflecting back on her crisis-inflected term, Ms. Lightfoot tells the Monitor that the pandemic made long-standing challenges from health care to housing to food insecurity suddenly “acute and urgent” – which, in a way, was a needed catalyst for change. And while “we haven’t solved every problem by a long shot,” she argues Chicago made real strides “coming together, not only as a city government, but with our partners in the community.”

“There’s a lot of lessons learned that I’m probably frankly going to be unpacking for the rest of my life,” she says.