‘We’re all on the same team’: Inside the Alaska model for US politics

Loading...

| Anchorage, Alaska

When Democrat Mary Sattler Peltola went looking to hire a chief of staff, she chose someone with hands-on experience and a deep knowledge of her home state, Alaska. He was also a Republican. Alex Ortiz’s last job was serving in the same role for her predecessor, Don Young, a giant in the state who died in 2022 after setting a record for longest-serving Republican congressman in United States history.

And he wasn’t the only Republican who Representative Peltola put on her payroll after winning a special election in August to replace Mr. Young. The congresswoman’s scheduler, another Young veteran, and communications director also came with experience working in the conservative trenches.

This is all but unheard of in the Capitol, where party loyalty can trump the most impeccable résumé. Indeed, colleagues in Washington asked Ms. Peltola if she were going to make her staff change their party affiliations.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onSome 71% of Americans want Democrats and Republicans to work together. Could “the Alaska way” offer a path back toward moderation?

“That was very surprising,” she says in a phone interview, adding that the questioning “set me back on my heels a bit.” Representative Peltola explains that she hired these staffers for their in-depth knowledge of Alaska, of the inner workings of the Capitol, and of the federal bureaucracy. It was a practical decision, “common sense,” she says. “I would never ask somebody to change their party affiliation. We are all on the same team, but we’re all still autonomous people on our team.”

For those Americans weary of polarization and its attendant lack of practicality, Alaska – which reelected Ms. Peltola to a full term in November, as well as moderate Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski – is offering a new model. And it’s prompting questions about whether the “Alaska way” might be repeatable in other states.

The nation is seeing in Alaska “a road map for political parties and political discourse across the country. ... I fully expect that, in the coming years and decades, to trickle into Congress,” says Zack Brown, former communications director for Congressman Young. Mr. Brown appeared in a campaign ad for Ms. Peltola for her reelection. In an October op-ed, he and other former Young-sters praised her positive campaign, bipartisan approach, and pledge to carry on Mr. Young’s legislative priorities for Alaska.

A key element in making this Alaska way possible is a different way of voting. Last year, Alaska put into practice a first-in-the-nation voting system of completely open primaries and ranked choice voting. It resulted in this red state sending two moderates to Congress. The representative is the first Democrat to occupy Alaska’s lone House seat in half a century, and the first Alaska Native ever elected to Congress. Yard signs featured Ms. Murkowski and Ms. Peltola together, and the Republican senator publicly said she would be voting for the Democratic congresswoman.

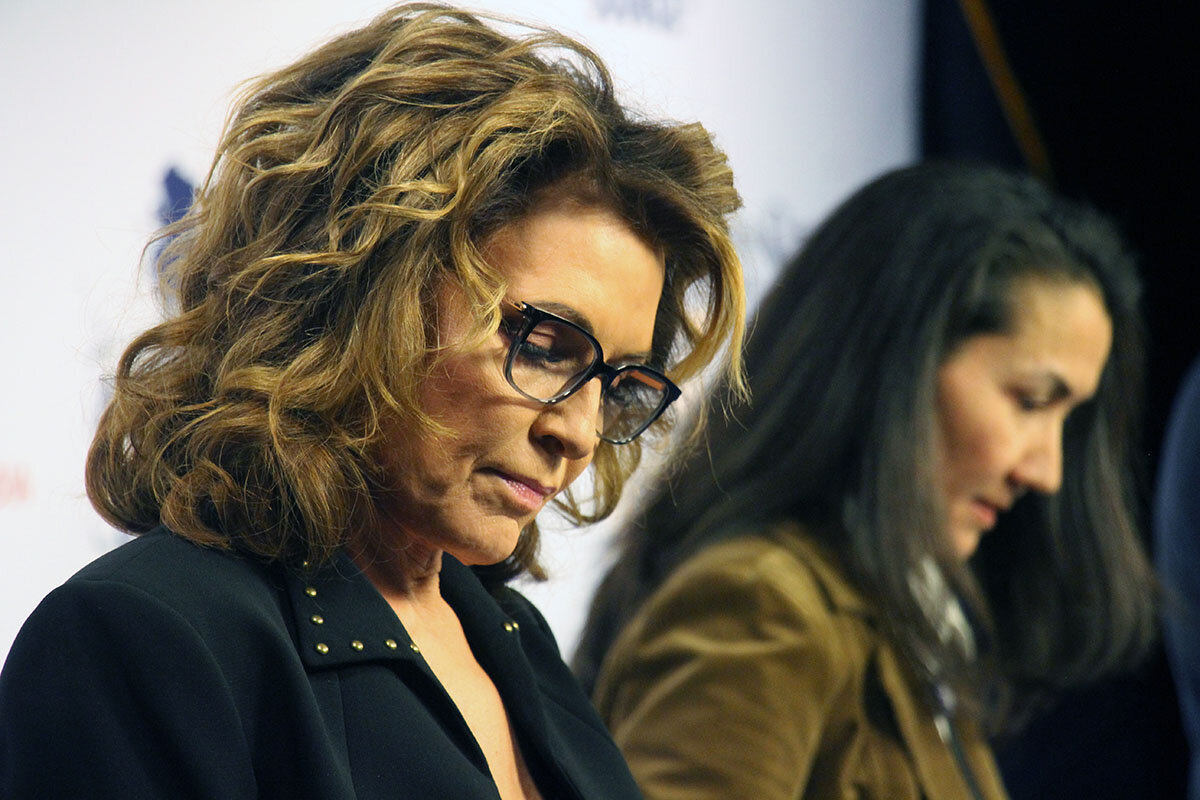

Much, too, has been made of the fact that Ms. Peltola never ran a negative ad as a candidate. Her chief rival was the Trump-endorsed Republican Sarah Palin – former governor, former vice-presidential candidate, and a politician whose star has faded in the brilliant night sky over the Last Frontier. Actually, they’re friends. That’s true, also, of Ms. Peltola and the late Mr. Young and his family.

Bipartisanship is also evident in the state Legislature, where Senate Republicans – despite having the most members – have decided to start the new year in Juneau with a majority coalition with Democrats. Both chambers have a recent history of bipartisan majorities stemming from fractures within the GOP, especially over fiscal issues. When the Alaska Legislature convenes Jan. 17, three GOP senators will be out in the cold – still on committees, but not eligible to lead them, nor to set the Legislative agenda or the rules.

Ivan Moore, who conducts independent polls at Alaska Survey Research, calls the November election “a win for moderation.” That’s unusual for this state, he says, given that it voted twice for Donald Trump and that for many years, the state Legislature has had Republican majorities, including not a few veto-proof ones.

Most Americans want compromise

Representative Peltola’s welcoming of common sense and continuity, even if found on the other side of the aisle, might well appeal to the ideological middle in America. According to Gallup, 37% of Americans in 2021 described their views as “moderate,” essentially tied with “conservative” (36%) and ahead of “liberal” (25%). Gallup also finds that independents now make up the largest political bloc in the country: Some 42% identify themselves that way, at least a third more than self-identify as Democrats or Republicans, though independents often lean one way or the other.

That tracks with a growing frustration with both parties, according to the Pew Research Center. With increased hostility, and large majorities of Democrats and Republicans now considering people in the other party to be “immoral,” the percentage of Americans who disapprove of both parties has reached its highest level in decades. More than a quarter have negative views of both parties, compared with just 6% in 1994.

Most Americans want the parties to work together. In another 2021 finding by Pew, 71% of U.S. adults acknowledge that “compromise in politics is how things get done, even if it sometimes means sacrificing your own beliefs.”

Ask Representative Peltola about her two worlds and she answers with a description of her parents – her father from a Nebraska wheat-farming family, all of them Republicans, and her Alaskan Native mother, with “100% Democrats” on her side. She uses the same phrase to describe both branches: “kindhearted, hardworking” people. Because of this experience, she says, she’s able to see people “for who they are, without labels,” whether they’re white or Native, Democrat or Republican.

“We all have the same basic needs. We all want to be seen. We want to be respected. We want to feel love,” she says. “We all love our kids. We love our parents. We’re all proud of who we are, and where we came from.”

Walks in both worlds

Observers point to Ms. Peltola as the personification of a bridge builder, both culturally and politically. She was raised on the Kuskokwim River in western Alaska and moves easily between the Yup’ik language and English. Natives and non-Natives surge with pride over her election. In October, she walked on stage to thunderous applause at the Alaska Federation of Natives Convention. Attendees spontaneously sang a hymn of blessing of the Russian Orthodox Church, to which she and many Natives belong. They also sang an Inupiat song of gratitude.

Ms. Peltola calls the Kuskokwim River community of Bethel, 400 miles west of Anchorage, her home. It’s a Yup’ik hub for area villages, and despite a subsistence culture, harsh climate, and reliance on weekly water deliveries, the city of roughly 6,000 has a “metro” feel, with a growing, increasingly diverse population and the third busiest airport in the state, says Ana Hoffman, who has known Ms. Peltola since they were in middle school. Residents have a sense of “place and purpose,” typified by summer “fish camp” when families are laying up fish for the winter, she says. Ms. Peltola started commercial fishing with her father when she was just 6 years old. As a young adult, she went on to serve a decade representing the Bethel region in the state Legislature, where she gained a reputation for collaboration.

Like most Alaskans, she’s all in for responsible development of Alaska’s natural resources, and for a time worked for a goldmine project. More recently, she was the executive director of the Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, working to protect fast-dwindling salmon runs in western Alaska, where many people rely on fishing and hunting to survive. She campaigned as “pro-fish, pro-family, pro-freedom.”

“She walks in both worlds,” says Sheri Buretta, chairman of Chugach Alaska Corp., one of 12 tribal corporations established under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. She explains that Ms. Peltola understands the remote, village world of Alaska Natives, who make up 20% of the population, and more urban Alaska, including “Los Anchorage,” where her husband, Gene “Buzzy” Peltola, has a home.

In an interview at her office, where Native masks and beaded headdresses adorn the walls and shelves, and giant plate glass windows reveal the majestic, snow-draped Chugach Mountains, Ms. Buretta describes Representative Peltola as someone who “understands how government works, how business works, how you work toward compromising to achieve the needs of the people.”

Face-to-face outreach

Andrew Halcro chokes up a bit when he recalls the first time he met Ms. Peltola. It was 1999, when he was a new Republican legislator in Juneau, and she, too, was a freshman – as was Ms. Murkowski. With the state facing a budget deficit, he arrived with the perspective that “by God, we’re going to cut the budget. Cut. Cut. Cut.” But after looking at the books, he realized, “there’s really nothing to cut,” explains Mr. Halcro, who is the chairman of Alaska Rent-A-Car and former president of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce.

And so, from his “ignorant, privileged, white-guy” perspective he gave a speech shortly after his arrival in which he called on rural Alaska to live without subsidies, to strengthen themselves, and build a better economy – having never set foot in remote regions except for sport. The blowback was swift and widespread.

“Within an hour or two, Mary Peltola was at my office door,” he recalls. She acknowledged that they were both new, and then offered to sit down with him and talk about rural Alaska, especially the energy cost equalization program, which he had just thoroughly derided.

“That created a relationship that really anchored me, and created such a desire to understand rural Alaska and help advocate for rural Alaska,” he says, wiping his cheeks.

The reality is, Alaska is a tough state to manage, explains Mr. Halcro, who has taken unsuccessful runs for the governorship and Congress as an independent. The state’s finances depend on the price and production of oil. Its vast terrain – the largest state in the country – is home to far-flung communities that may have just a couple of dozen residents. As newcomers in the state House, he, Ms. Murkowski, Ms. Peltola, and others created a bipartisan fiscal policy caucus to tackle structural budget problems. Only an alcohol tax survived, and the state is eating through savings as it struggles with out-migration and bumps along the bottom compared with other states in education, public safety, and economic growth.

Ms. Peltola’s longtime friend Ms. Hoffman, who is co-chair of the Alaska Federation of Natives, describes her election as “restorative” – for democracy, and yes, for fish, with the supply of salmon reaching a “crisis” on the Kuskokwim River. Indigenous people and others in the lower 48 have noticed the new voting system and its outcome, she says. “Mary’s election is one that helps to renew people’s confidence in our democracy – beyond Alaska,” says Ms. Hoffman, who is also the president and CEO of the Bethel Native Corp.

The Alaska spirit

But can the Alaska model be repeated?

A strong independent streak – some describe it as libertarian – runs through the state that calls itself the Last Frontier. An astonishing 57.6% of registered voters here are either nonpartisan or undeclared. As pollster Mr. Moore explains, the vast majority of Alaskans came from the lower 48 to get away from the lower 48, including its take-no-prisoners politics. “In certain respects, we’re fundamentally different,” he says. That difference, he suggests, makes Alaskans open to new ideas, like open primaries and ranked choice voting.

A cooperative spirit also permeates the state. It’s a stunningly beautiful place, but it can also be cold, dark, remote, and dangerous. You never know when you might get a flat tire in the middle of nowhere, depending on help from a passerby (Mr. Moore had just such an experience, after hitting a deep pothole). Or when your boat might be in a remote slough and you need to borrow 5 gallons of fuel. Alaskans have an “ingrained feeling of mutual survival and that leads to an ingrained reasonableness,” says Mr. Moore.

While it’s a huge state, it’s also one of the least populated – about the size of Washington, D.C. Ms. Peltola mentions 1 degree of separation between Alaskans. Everyone knows everyone else.

For instance, she and Ms. Palin were both pregnant when Ms. Palin was governor and Ms. Peltola was in the state Legislature. Ms. Palin gushed praise for her friend during the 2022 campaign, complimenting her as a “real Alaskan chick” in texts after Ms. Peltola won the special election. Likewise, Ms. Peltola’s father worked for Mr. Young in his early years, and her mother was expecting Mary as she campaigned for him. When one of Mr. Young’s daughters unexpectedly presented Ms. Peltola with her father’s prized bolo tie at the Native convention last year, it was an emotional moment.

These circumstances may set Alaskans apart, but it doesn’t make a spirit of cooperation exclusive to them, says Ms. Peltola. She recalls growing up in a time when the spiciest rhetoric in national politics was Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan digging at his opponent, President Jimmy Carter, with the debate quip “There you go again.” America once had a level of civility and decorum, and it can recapture it, she believes.

“We start with ourselves,” she says, imploring elected officials and community leaders to lead by example. “Attitudes are contagious. If enough people are doing this, it will catch on. This was our culture before.”

New voting process

In 2020, Alaskans approved a ballot initiative to adopt nonpartisan open primaries. Any registered voter can vote for any one candidate, with the top four winners advancing to the general election. At that point, ranked choice voting kicks in. That’s when voters can rank their choices for each office in order of preference. If no candidate gets 50% plus 1, votes are retabulated as the bottom candidate is eliminated and that candidate’s votes are redistributed according to the preferences until there is a winner with majority support.

The process is meant to have a twofold effect: ensuring that candidates who might have broad support are not filtered out by a closed partisan primary, and encouraging a more civil tone and wider appeal as candidates seek to go beyond their base to attract voters who may designate them as their second choice.

“The overall purpose is to create systems that reward candidates with broad, majority support,” says Richard Pildes, an election law expert at New York University School of Law. “There’s no reason [the Alaska model] cannot be adopted in other states.”

Indeed, last November, Nevada voters approved a similar ballot measure. However, because it involves changing their state constitution, they will have to approve it again in 2024 for it to take effect. Maine has been using ranked choice voting since 2018 – in both state and federal primaries, and in general elections for federal candidates only. In 2020, it was expanded to presidential elections. Beyond that, two counties, 58 cities, and military and overseas voters in six states use ranked choice voting, according to FairVote, which promotes the process.

“I’m kind of a fan” of the new voting system, says Cathy Giessel, who will be the Republican majority leader in the Alaska Senate when it convenes later this month. She didn’t always feel this way, she notes. “I think this will allow the voters – especially what sometimes people call the ‘silent majority,’ the people in the middle – the opportunity to really have a voice and not just have the parties run these elections,” she says on a bright winter afternoon at the University of Alaska Anchorage, where she serves on the Citizens Advisory Board to the School of Nursing.

State Senator-elect Giessel has directly benefited from the new process – and learned from it. Previously the Senate president, she lost reelection in 2020 when she was primaried from the right. This time, she cast her net much wider, knocking on 8,612 doors in a vigorous retail campaign. She found a lot of former Republicans, as well as Democrats whose vote she courted as a possible second choice by emphasizing common ground. What she heard repeatedly was that people want basic problems solved. They don’t care about the politics.

“I talked to some really interesting people, that, if this had been a closed primary, I would not have gone to their door. ... That really helped me see a bigger picture,” says Ms. Giessel. It paid off in the end. Voters from her Democratic opponent who ranked her second gave her a comfortable majority. The same thing happened with Senator Murkowski, who ran against Trump-endorsed candidate Kelly Tshibaka. Ms. Murkowski is reviled by many Alaska Republicans for voting against the repeal of “Obamacare” and in favor of Mr. Trump’s impeachment, among other reasons.

What about the political parties?

Snow falls gently as Alaska’s former Lt. Gov. Loren Leman walks into New Sagaya City Market in downtown Anchorage. Few people realize it yet, but it’s the start of a “snowmaggeddon” that’s going to dump 4 feet over 11 days and bring the city to a near standstill. Inside, it’s warm and cozy – a liberal hangout, the Republican notes, but it’s got great coffee (an obsession here).

As lieutenant governor in the early 2000s, he oversaw Alaska’s elections. He strenuously opposes the new voting system. “It makes political parties increasingly irrelevant in terms of influence,” he says over a hot cuppa joe. “Political parties exist for a reason. People associate with them, because in general, they set up values that people can say, ‘Well, I agree with most of those values.’”

It’s not an uncommon criticism, along with complaints that Alaska’s new system is too complex (though 79% of voters polled found it “simple”) and that it took more than two weeks to tally final votes – inviting suspicions about fraud. Neither does the system deliver on its promise to take away power from dark money special interests, he says. In an opinion piece opposing the measure, he wondered about the promise to produce a breed of leaders that is “wiser, kinder and more capable.” What about San Francisco, he wrote, which has used the ranked choice voting method for years, and is riven with homelessness and other problems that elude its leaders?

Mead Treadwell, another Republican former lieutenant governor opposed to the new voting system, notes that because of the new way of voting, Republicans had no opportunity to unify behind a single primary winner. In the case of Ms. Peltola, her two Republican opponents, Ms. Palin and Nick Begich, went at each other hammer and tong, somehow missing the fact that they were disincentivizing their supporters from ranking either of them as their second choice. It was redistributed Begich voters who eventually pushed Ms. Peltola into a comfortable majority. “We never had a chance to coalesce,” says Mr. Treadwell.

Alaska’s new voting system passed by a narrow margin of only 4,000 votes, and efforts are underway to repeal it through a new ballot measure. That may well happen, says Mr. Moore, the pollster, but he is mystified by conservatives’ objections. Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy won reelection on the first round of counting. Registered Republicans heavily outnumber Democrats, and typically there are nearly twice as many Republican candidates. No question, the new system – particularly the open primary – had a “huge” effect, but at the same time, the winners ran successful campaigns, with Ms. Murkowski and Ms. Peltola also helped by voters who support abortion rights.

Mr. Moore is not alone when he describes Ms. Peltola as a “first-rate candidate.” She has authenticity, he says – that “undefinable thing that only some people have.” It reminds him of Ms. Palin, in her early days.

Ms. Peltola is relatable to ordinary Alaskans because she does the things they do, says political strategist Jim Lottsfeldt, whose firm created a super political action committee, Vote Alaska Before Party, to try to get her elected. Like many Alaskans, she can “fill a freezer,” as the saying goes. A campaign ad showed her at summer fish camp, filleting salmon. She owns more than 170 guns and reminded Alaskans that she hunts.

“Ranked choice voting opened the door for her,” says Mr. Lottsfeldt. “But she didn’t stumble. She didn’t walk through the door, she just sprinted.”

The road ahead

Now comes the hard part. Unlike her few months in Congress last year, Representative Peltola is suddenly in the minority party. It is Republicans who will set the agenda in the House, not Democrats. But as a moderate in a chamber where Republicans have only the narrowest of margins, she has leverage as a potential swing vote.

She also has the bully pulpit, and an administration that’s supposedly on her side. She recently teamed up with Senator Murkowski and Alaska Sen. Dan Sullivan, also a Republican, to successfully pressure the administration to declare fisheries disasters in Alaska so that fishers can get relief funding – which she successfully lobbied to include in the massive year-end spending bill.

Like Mr. Young, she’ll be measured in Alaska by what she does for the state, what she can bring home in development projects, jobs, funding, and constituent services. What many people might not realize, she says, is that policy is influenced by relationships. And so she’s learning the names of all 434 of her House colleagues, while also carrying on the tradition of “fish Fridays” that she held in the Alaska House, where she shared salmon with her fellow lawmakers.

One of her top goals is to reauthorize the 1976 law that manages fisheries in U.S. waters, the Magnuson-Stevens Act. Last fall, she literally talked turkey on the House floor with the incoming GOP chair of the Resources Committee, Rep. Bruce Westerman of Arkansas. Stuffing or dressing? His mom makes dressing, which she learned involves cornbread. He also told her how much he loved Mr. Young, and how he wants to help her move his legacy forward, including reauthorizing the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

Representative Peltola is well aware that any vote in divided America is “going to anger 50% of the people.” For instance, she’s inclined to vote for an energy independence bill, which Democrats oppose but which Republicans say they plan to quickly introduce. It would ramp up domestic fossil fuel production and critical mineral mining.

While she can’t solve the partisan divide in America, she says she can do her part as a House member.

“We have formidable foreign challenges. We have formidable domestic challenges. Americans cannot afford for us to be engaging in partisan bickering,” Representative Peltola says. “We have got to focus on our real challenges and find solutions to those challenges.”

Editor’s note: Maine’s implementation of ranked choice voting has been clarified.