Voters elect Congress. Congress elects its leaders. How that works.

Loading...

| Washington

Voters directly elect representatives to serve in Congress, but the leaders of those 435 House members and 100 senators are chosen through an internal – and, for many Americans, largely opaque – process.

Yet congressional leaders play a critical role in setting legislative agendas, wrangling votes, and communicating party priorities to the public.

The House has three main leadership roles: speaker, majority leader, and minority leader. The Senate has majority and minority leaders. In both chambers, the majority and minority whips also play an important, albeit secondary, role.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAmerican voters elect members of Congress, but House and Senate members choose their leaders. Understanding leadership roles and their powerful influence is part of informed citizenship.

What do congressional leaders actually do?

The speaker of the House – currently Democratic Rep. Nancy Pelosi of California – is the most powerful member of that chamber, controlling everything from what legislation makes it onto the House floor for consideration to who sits on what committee. The speaker is also second in line of succession for the presidency, after the vice president.

The majority leader, the speaker’s right hand, tracks the maneuvering of the minority party and handles the day-to-day details of floor proceedings.

The minority party leader is its floor leader – but the House gives the minority far less power than the Senate, and the House minority leader has fewer strategic tools at their disposal.

Majority and minority whips liaise between the members and leaders of their party, helping to “keep everyone in line,” says Philip Wallach, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute – or at least alerting the leaders if a member intends to break ranks on a vote. “Party leaders really don’t like being surprised by anything,” he says.

In the Senate, the majority leader holds the most important role, followed by the minority leader and the whips, who play much the same role as in the House.

The vice president is the president of the Senate – although it’s rare for the vice president to actually preside over Senate proceedings, says Dr. Wallach.

In general, the Senate imposes more hurdles for leaders to go through. “A lot of what happens in the Senate requires unanimous consent,” says Dr. Wallach, while the House typically employs unanimous consent only for noncontroversial matters. That forces Senate leaders to find ways of doing things that both parties will find acceptable.

How are leaders selected?

In the House, the Democratic and Republican caucuses nominate a candidate for speaker, to be chosen in an open election on the floor when the new Congress convenes. Minority and majority leaders and whips of both chambers are elected in their party caucus prior to the swearing-in of a new Congress.

For the upcoming Congress, the leaders and whips of both parties in both chambers have already been elected, by secret ballots.

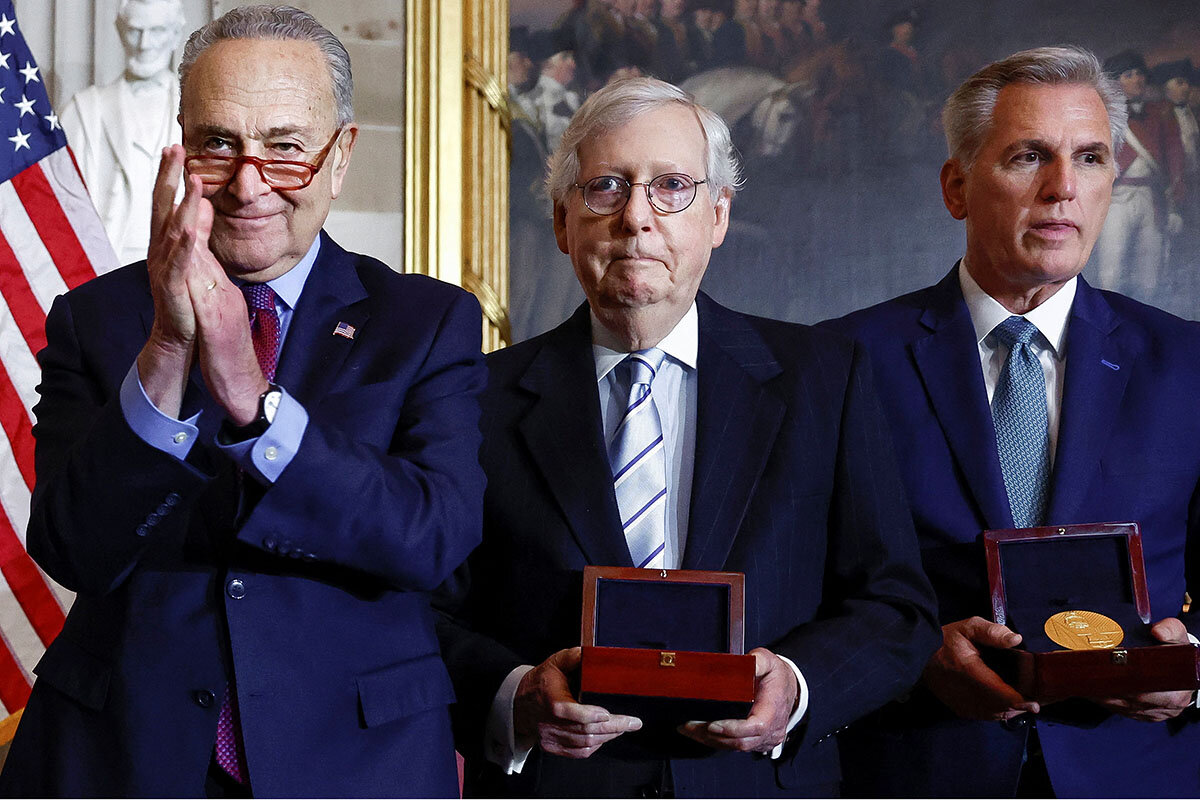

The speaker vote is expected Jan. 3. California Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the Republican nominee, is still working to secure the necessary votes to win the gavel. A winning candidate needs a majority of votes from those who are present and voting that day, which means Mr. McCarthy can only afford to lose a handful of Republicans. It’s possible the vote could go to multiple ballots, though such an event would be rare.

Candidates often win support based on geography or ideology, or strategic fundraising and campaigning for allies, says Dan Glickman, a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and an 18-year veteran of the House.

History shows that if leaders get reelected in their districts by voters and the balance of each chamber remains the same, they’re frequently reelected to their congressional leadership role as well. There are advantages to having the same leaders serve multiple terms, says Mr. Glickman. But after a point, it can also create a kind of stagnation. In the House in particular, younger lawmakers may have less of an incentive to continue to serve if they see no path to leadership roles – a criticism that was lodged at the current Democratic slate of House leaders before many of them decided to step aside next month.

Why should any of this matter to voters?

Americans have a vested interest in understanding the workings of Congress, which frequently might seem arcane but has a direct impact on their lives.

“Congress is one-third of our government and the closest of all the branches to the people,” says Mr. Glickman, who is also a former secretary of agriculture.

The speaker of the House is particularly consequential because that person is the third most powerful leader in government after the president and vice president, notes Sara Angevine, an assistant professor of political science at Whittier College.

Skilled congressional leaders can “negotiate policy through compromise and deliberation,” she adds. That’s become more difficult in an age of extreme partisanship and polarization – but it’s a vital thing to model for the electorate. “[Leadership] roles and the principles of deliberative democracy are very, very important for the entire electorate to be aware of.”