‘Where’s the middle?’ In closely divided US, a country waits.

Loading...

| Haverford and Warrington, Pa.; Tempe, Ariz.; and Liberty County, Ga.

Why did the predicted red wave lap onto the beach as a relative ripple?

Some key races in the 2022 midterm elections have not yet been decided, but the vote’s bottom line seems clear: Republicans did not do as well as they hoped. Democrats showed unexpected strength, given the political fundamentals of President Joe Biden’s unpopularity and voters’ widespread economic concerns.

If there is a message from the razor-thin midterms, it could be: American voters care about democracy. Candidates who echoed former President Donald Trump’s false claims about the 2020 election lost every governor’s race except in Arizona, which remained too close to call Wednesday.

Why We Wrote This

Democrats overcame historical trends and poor economic conditions in a number of key races, though the full picture is still emerging. Voters in particular seemed to reject statewide candidates who denied the 2020 results.

Other immediate takeaways: Candidate quality still matters, with polls pointing to weak Republican candidates in some important Senate and gubernatorial races. And in a post-Roe America, abortion is a driver at the ballot, with voters in five states – Michigan, Vermont, Kentucky, Montana, and California – all voting in favor of abortion rights.

“Even though there is a lot of latent dissatisfaction about the way the country is going and the state of the economy and the performance of the president, there just isn’t an enthusiasm for the alternative,” says David Hopkins, a political scientist at Boston College.

As of this writing, control of both houses of Congress remained undetermined – although the GOP appeared to be in a better position to gain a majority in the House of Representatives. That could presage two years of bitter conflict, with a Republican House launching a wide range of investigations into Biden administration activities.

Control of the Senate is also unclear, and may remain so until a Dec. 6 runoff in Georgia between Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock and GOP challenger Herschel Walker. Mr. Walker, a former football star endorsed by former President Trump, ran well behind other Republicans in the state, especially Gov. Brian Kemp, who handily won reelection. Other weak Trump-endorsed candidates may have cost the GOP Senate seats in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire.

Meanwhile, suburban House seats outside Philadelphia, Chicago, Atlanta, and other cities that used to be solid red but turned purple during the Trump presidency went for the Democrats on Tuesday.

It was not a good election for Mr. Trump, and his grip on the party may have been weakened, says Gary Jacobson, emeritus professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego.

“He’s the greatest mobilizer the Democrats have,” says Professor Jacobson.

Pennsylvania swings blue

In Pennsylvania, now one of America’s most contested battleground states, Mr. Trump’s preferred candidates did poorly. Trump-endorsed television personality Dr. Mehmet Oz lost a Senate race to Lt. Gov. John Fetterman. The former president’s gubernatorial endorsee, Doug Mastriano, who has denied President Biden was duly elected and who was present at the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, lost to Attorney General Josh Shapiro.

For some Pennsylvania voters, Mr. Trump’s endorsement was a negative.

Tom McDonald, a retired high school teacher interviewed outside a polling place on the Haverford College campus, says that he formerly registered as a Republican and often voted split tickets. But now he is a registered Democrat, and “the fact that the Republican Party has moved off the rails to the right” has pushed his vote to the left.

This year he voted straight Democratic, and says the issues he was most motivated by include protecting voting and abortion rights.

Meanwhile, Helene Dunn, who works for a local water authority, voted a straight Republican ticket.

Standing outside Central Bucks South High School in Warrington, Pennsylvania, Ms. Dunn says, “I am horrified that with the worst economy, an absolutely frightening border crisis, and crime through the roof, the only thing people care about is abortion.”

That does not mean Ms. Dunn was satisfied with her choices. She says they were the worst she’s ever seen, on both sides.

“They both seem so extreme. Where’s the middle?” she says.

Bourne Ruthrauff, a lawyer from Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, also voted Republican – except he did not vote for governor or lieutenant governor.

Recent presidents have all overstepped their power with executive orders, says Mr. Ruthrauff. We need a “responsible” Congress, he adds.

“The Republicans have to put Mr. Trump in the rearview mirror, and that goes back to the rule of law,” he says.

The view from Georgia’s Liberty County

Georgia could be the state on which control of the Senate will turn. Democratic Senator Warnock had a slight lead over GOP challenger Mr. Walker, but did not reach 50% of votes cast. Under state law that means the pair will face off again in a runoff, set for Dec. 6.

But not every part of the state may be hotly anticipating that coming choice.

Georgia’s Liberty County is a largely rural area south of Savannah. Divided equally between Black and white residents, it is home to the massive Fort Stewart Army base, the largest U.S. military installation by land mass east of the Mississippi River. It leans blue for the most part, though in past years it went for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Interviewed outside their polling place, Natalia and Larry Carmichael, both Army combat veterans, say Liberty County represents a rural outpost struggling to do right by its citizens. Mr. Carmichael bemoans how there’s no shade on the few basketball courts available for young players.

“Politicians say what they want you to hear, and then they go and do whatever they’re going to do,” he says. “That’s both parties.”

Ms. Carmichael says she was no fan of Mr. Trump, but he did catch her attention with how he tried to remind Americans of the nation’s inherent greatness.

“We have to regain some of the values that we’ve lost. We have to be a place where we can be proud of who we are,” she says.

Linda McKnight, a former government employee, does see larger American stakes in her vote. She voted for Democratic candidate Ms. Abrams – who lost to Governor Kemp – because of Ms. Abrams’ work to bolster voting rights.

“She walks the talk,” says Ms. McKnight.

Arizona independents now choose a camp

While much of the midterm vote appears to have proceeded smoothly, it remains possible that charges of voter fraud could roil some states. Arizona is one place where that might happen.

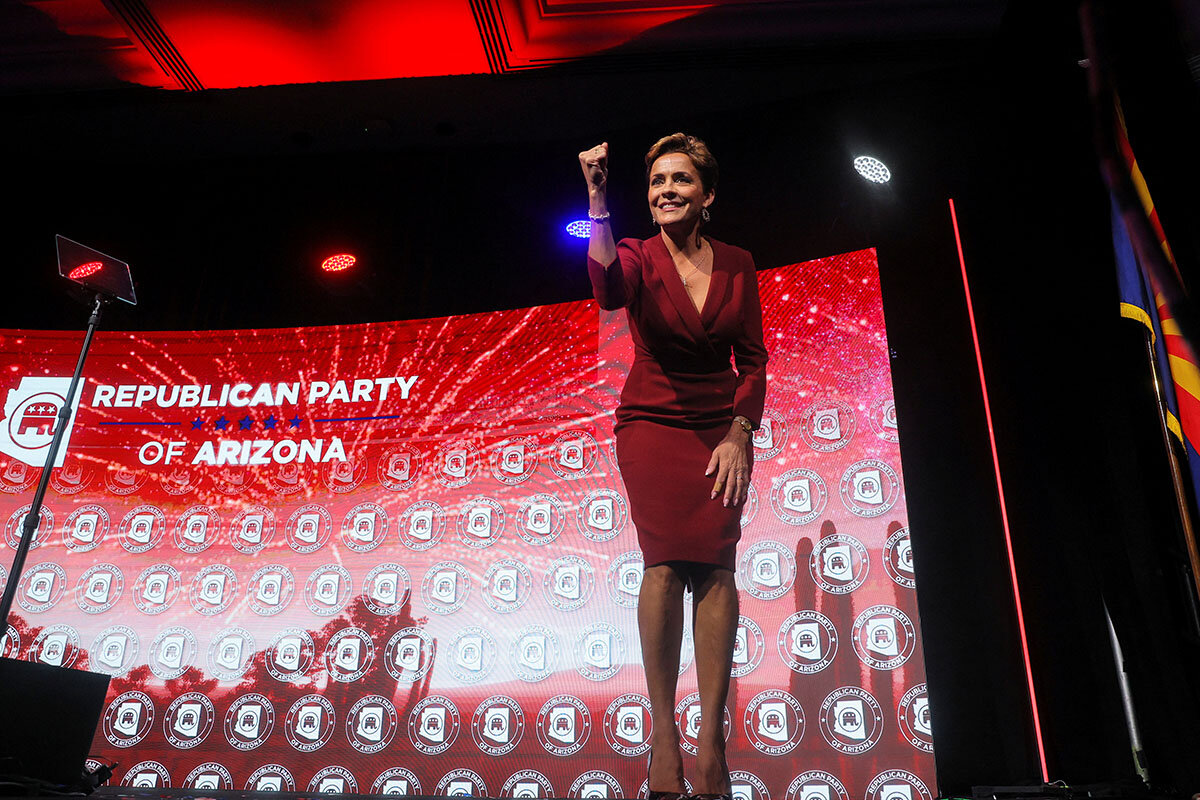

GOP gubernatorial nominee Kari Lake has amplified Mr. Trump’s false claim that he won the 2020 election. She is trailing narrowly in her own election, and has implied she has doubts about the counting.

“We need honest elections and we’re going to bring them to you, Arizona,” Ms. Lake said Tuesday night in a speech to supporters. The midterms are “Groundhog Day” repeating the 2020 alleged widespread fraud, she said.

Arizona is a state where voters who once may have been independents now seem firmly entrenched in partisan views.

James Northcroft is a warehouse worker who lives in Tempe. A former Obama and Clinton voter, he voted for Republicans this year, he says.

“The inflation, the need for law and order, is really bad. Not so much around here, but in New York City criminals get out [of jail] the next day after they do something,” he says in an interview outside his Tempe polling place.

Mr. Northcroft says he only watches the conservative site Newsmax, or late-night Fox News, because everything else is “fake news,” as Mr. Trump continually repeats.

“I think voting is really important – I wish it was 2024 because I want to get Trump or [Florida Gov. Ron] DeSantis back in there. Someone has got to start fighting this radical socialism,” he says.

Carrie Mendoza, an office account manager, has a far different take on the politics of 2022.

“Our democracy really is at stake in this election, and that’s huge,” she says, walking to her car outside the polling place.

A registered Democrat, she says she votes down the middle. In the past she marked a ballot for GOP Sen. John McCain. But she won’t even consider voting for Republicans now.

“And it’s not because the Democrats have it all right. It’s because I can’t take the chance of a Republican winning and have them not believe in our election system, or wanting people to be afraid.”

Ms. Lake may still prevail in her Arizona race. She was one of about 370 Republican candidates in the midterms who questioned the validity of the 2020 election, in one way or another.

At least 168 of those candidates won. Eighty-seven lost, as of Wednesday afternoon.

But many of those who won were running for legislative seats or other offices without direct election responsibilities. Some of the deniers who would have been best positioned to affect election results, such as Mr. Mastriano in Pennsylvania’s gubernatorial race, lost.

Twelve deniers or questioners of the 2020 vote ran for state elections chief, according to CNN fact-checker Daniel Dale. Six lost, including candidates in Michigan, Minnesota, and Vermont. Four won, including candidates in Wyoming and Alabama. Two have yet to be determined.

“We’re in really unusual times in the United States now, and our battles are not normal politics. They’re not about public policy. ... Instead, what the battle is about now is democracy itself,” says Suzanne Mettler, the John L. Senior professor of American institutions at Cornell University.

It’s heartening that many Americans who are worried about democracy turned out to vote on that issue, says Professor Mettler. But many election deniers will be in office as the political clock ticks toward the 2024 presidential election.

“We’re not out of the woods,” she says.