Biden ran on competence. A slew of challenges are testing that promise.

Loading...

| Washington

The contrast was meant to be sharp: a seasoned Washington veteran replacing a president who arrived a political novice and was voted out after one tumultuous term.

Joe Biden’s campaign watchwords – competence, experience, empathy – applied both to himself and to the team he would bring in. But since Inauguration Day, one challenge after another has tested the new president and his administration in ways both foreseen and unimagined, denting the reputation of a man who took office amid high hopes.

A summer COVID-19 surge fueled by the delta variant dashed expectations of a return to quasi-normality, laying bare the limits of government. A different surge – of migrants at the southern U.S. border – has also put the Biden team on the defensive. The Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack last spring, disrupting access to fuel up and down the East Coast, found the nation’s cybersecurity apparatus wanting.

Why We Wrote This

New administrations have learning curves. President Biden’s current struggles may reflect in part a team that hasn’t fully ramped up and a bureaucracy that’s not nimble enough to meet 21st-century challenges.

And following the United States’ chaotic, deadly exit from Afghanistan, President Biden is digging out of his biggest foreign policy crisis yet. The Taliban have returned to power. Americans and Afghans qualified for evacuation are still trying to get out – though some dual nationals, including Americans, were able to leave Kabul on Thursday. U.S. relations with NATO allies have been damaged.

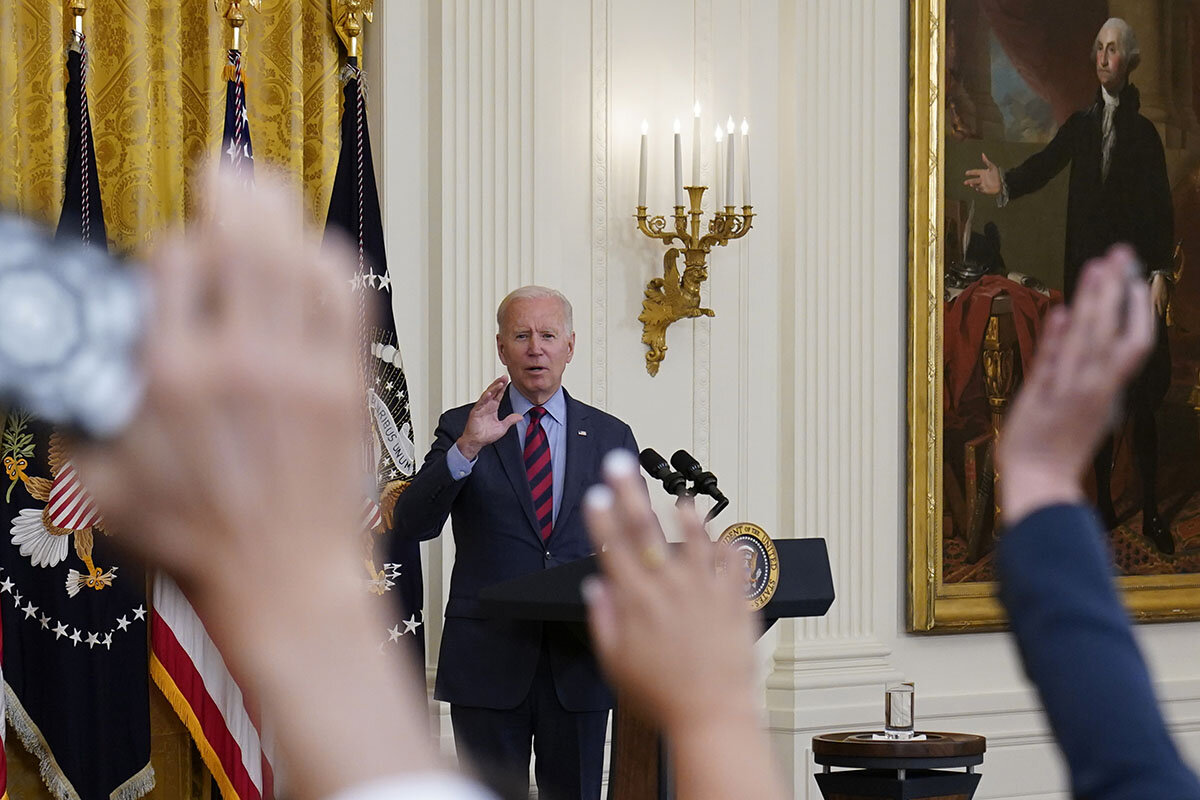

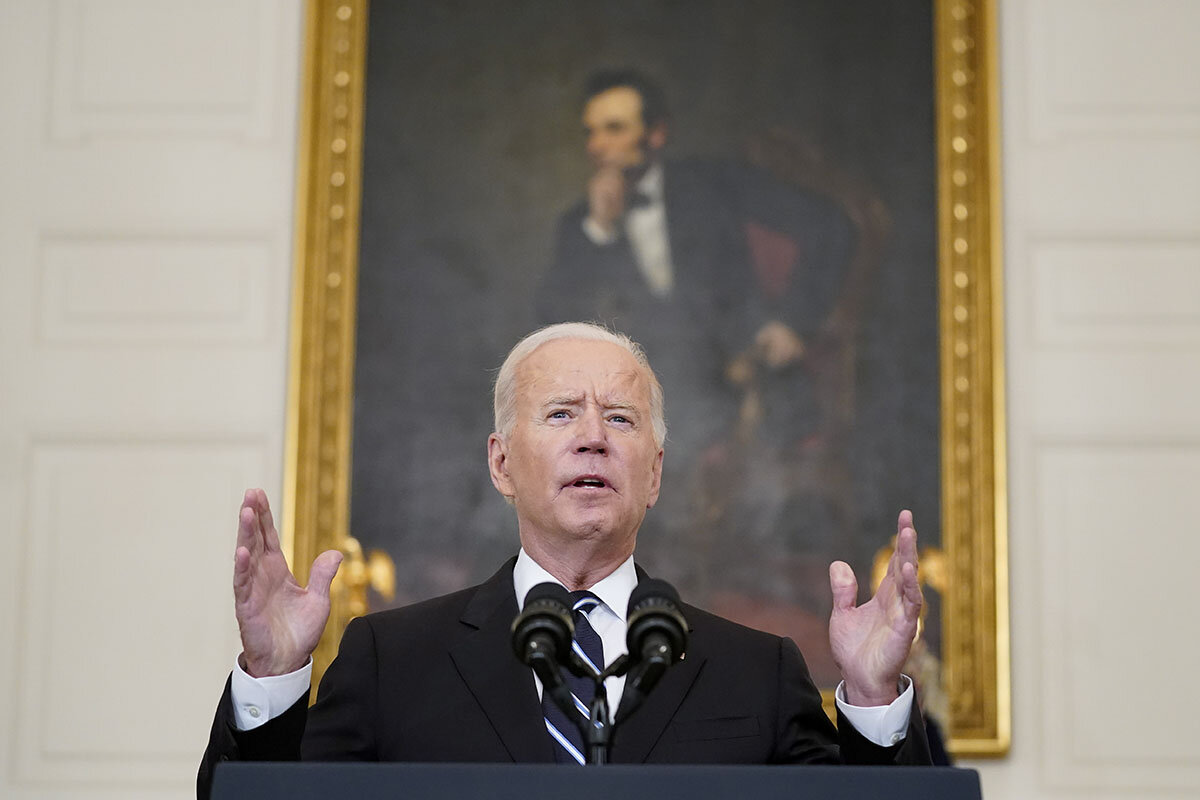

Mr. Biden’s biggest challenge of all – the pandemic – threatens to engulf his presidency, with obvious major implications for public health, the economy, education, essentially all aspects of American life. On Thursday, the president laid out a new six-pronged strategy to fight the delta variant and increase vaccinations.

“We have tools to combat the virus, if we can come together as a country and use those tools,” Mr. Biden said in a televised address from the State Dining Room in the White House, at times visibly frustrated with the resistance he says has slowed the U.S. efforts to fight the pandemic.

“First years are problematic for presidents,” says presidential historian Russell Riley of the University of Virginia. “There’s a tendency to a kind of innocent arrogance in the early part of an administration. You think that because you succeeded in winning the White House, your judgment is golden.”

For President George W. Bush, the first year in office was punctuated by the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 – a historic “failure of imagination” on the part of an unprepared U.S. government, as The 9/11 Commission Report famously stated. The ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April 1961 is another prime example of a new president, John F. Kennedy, stumbling badly early.

President Bush came to office having never served in Washington, only as Texas governor. President Kennedy, barely in his 40s, came straight from the Senate. In contrast, Mr. Biden brings to the table more experience in elective office than any American president in history.

Still, even eight years as vice president isn’t the same as actually having the top job, says Professor Riley, co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at UVA’s Miller Center. The president’s team, no matter how close to the president or talented as individuals, won’t have fully jelled this early on, he adds. “The only way to mount the learning curve is over time.”

A “slow-moving horror show”

Regarding the U.S.’s 20-year occupation of Afghanistan, Mr. Biden said he had to abide by the deal the Trump administration had struck with the Taliban to withdraw U.S. forces, or risk prolonging a “forever war.”

His insistence in July that the U.S. would not see a repeat of the chaotic 1975 withdrawal from Vietnam was soon belied by facts on the ground. Yet even as U.S. intelligence began to see that the Afghan government could collapse imminently, Mr. Biden didn’t waver. America was pulling out.

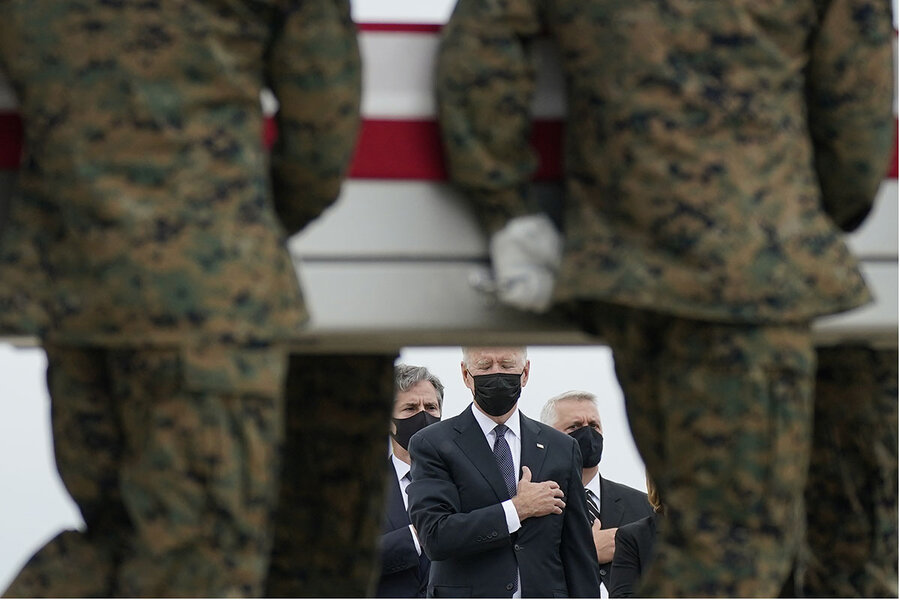

The U.S. military ultimately evacuated some 124,000 people, initially amid heartbreaking images of Afghans desperately clinging to a U.S. cargo plane as it took off – and the horrific terror attack at Kabul’s airport on Aug. 26 that killed 13 U.S. service members and scores of Afghans.

Overall, the U.S. withdrawal was a “slow-moving horror show, though we did regain our balance a bit with that superb air evacuation,” says retired Brig. Gen. Peter Zwack, a former senior U.S. military intelligence officer in Afghanistan.

By the Aug. 31 pullout deadline set by Mr. Biden, the U.S. was unable to evacuate between 100 and 200 Americans who wanted to leave, the administration acknowledges. And most Afghans who applied for Special Immigrant Visas, or SIVs – intended for those who helped the U.S. government – are still in Afghanistan.

The backups in the SIV program represent another challenge of governance: how bureaucratic processes, albeit often legitimate, can delay action.

Another example, in a different context, is the slow disbursement of federal rental-assistance money intended to prevent evictions during the pandemic. By the end of July, only 11% of the $5 billion funding the program had been disbursed – in part because of the nation’s federalist system. The money is distributed by state and local governments.

The Treasury Department has announced changes to speed up the process. Adding urgency to the matter, the Supreme Court two weeks ago struck down a national moratorium on evictions.

Looking at American government writ large – from fighting terrorism to helping people in need – there’s an obvious problem, says Elaine Kamarck, director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Effective Public Management.

“It is not agile,” says Ms. Kamarck, who served in the Clinton White House.

“Essentially the 20th century was a century of bureaucracy. We created bureaucratic structures, which did a good job of meeting the issues of the day. But as we move into the 21st century, those structures are a little bit clunky when it comes to dealing with 21st-century problems.”

Take the issue of terrorism. The U.S. invaded and conquered an entire country – Afghanistan – to carry out what is in effect a police function: stopping attacks.

Then there’s cybersecurity, which defies the notion of jurisdiction, the essence of law. “We are having trouble adapting government organizations to this very new and fluid phase we’re in,” Ms. Kamarck says.

Max Stier, CEO of the nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service, comes back to the fact that the Biden administration is still getting up and running – with a lot of top jobs vacant. Of the 800 government positions the partnership tracks, only 127 have been confirmed by the Senate. The Food and Drug Administration, for example, still doesn’t have a permanent commissioner – in the middle of a pandemic.

“It’s the equivalent of Super Bowl Sunday coming on, and your team has on the field the quarterback and the center but none of the offensive line,” Mr. Stier says. “It’s crazy. And we’re deep into the administration.”

“That’s actually a really important component of what’s breaking down now and what has broken down before,” he adds.

A reset for the pandemic?

Early in his presidency, Mr. Biden seemed keenly aware of managing public expectations. His guiding principle seemed to be “underpromise, overdeliver.”

That came through in his early handling of COVID-19. A month before taking office, Mr. Biden announced that in his first 100 days, 100 million Americans would get vaccinations. By the 100-day mark, more than 220 million shots had been administered.

Since then, any expectation of an orderly national effort to confront the pandemic has fallen by the wayside. When it comes to mask mandates in public schools, for example, governors either require them, forbid local jurisdictions from imposing mandates, or state no position.

There’s also been a disconnect between the White House and two key federal agencies – the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – over when and for whom to recommend certain booster shots. A decision is expected soon.

On Thursday, Mr. Biden’s new “action plan” on COVID-19 contained six broad categories. The provisions include a requirement that all companies with 100 or more employees ensure workers are vaccinated or tested weekly; potential disciplinary measures against federal employees who refuse to get vaccinated; and a call for all schools, teachers, and staff to set up regular testing consistent with CDC guidance.

Mr. Biden is losing ground with the public in his handling of the pandemic – from 62% approval on July 1 to just over 52% now, according to the FiveThirtyEight analysis of polls.

Republicans, for their part, are casting Mr. Biden as a modern-day Jimmy Carter, the one-term president whose tenure included the Iran hostage crisis, gas lines, and major economic woes.

All presidents go through rough patches, and their ability to weather them depends on many factors – including political skill and events beyond their control.

Mr. Biden’s job approval ratings held steadily above 50% from January onward, but went “underwater” – more disapproving than approving – in mid-August and have stayed there.

It’s too soon to say if Mr. Biden can recover politically, or how the recent rough sledding might influence the 2022 midterms. Most Americans, of both parties, agree with the decision to get out of Afghanistan. The problem was execution. Political analysts surmise that by November of next year, memories of the messy and tragic pullout will have faded.

But in the meantime, Mr. Biden needs other things to go well – handling of the pandemic, the economy, national security.

Paul Light, a professor of public service at New York University, praises Mr. Biden and his staff as “among the most accomplished policy designers we’ve ever seen in the White House.”

But he dings them on policy delivery: “They have a confidence in government that I think is misplaced.”