In pandemic economy, workers have leverage. Will it boost unions?

Loading...

Richard Bensinger, an organizer with Workers United, has been helping workers form unions for four decades. But he says he’s never worked with a group as passionate as the Starbucks baristas in Buffalo, New York.

With Starbucks’ quarterly revenue hitting an all-time high earlier this year, employees across three Buffalo stores say they have been asked to do more work for the same pay despite health risks. Meanwhile, they saw their unionized colleagues at another Buffalo coffee chain, Spot Coffee, vote to temporarily close their stores when pandemic caseloads were high.

So last week, more than 50 Buffalo employees announced a plan to form their own union, called Starbucks Workers United. If successful, it would be the first for the nearly 9,000 company-owned Starbucks locations in the United States. Three days after their initial meeting, a majority of the stores’ eligible employees had signed cards in favor of unionizing.

Why We Wrote This

What lies behind the growing support for unions in the U.S.? A defining characteristic of Generation Z – the push for social justice – may be part of the answer.

“It was pretty old-fashioned,” recalls barista Jaz Brisack, describing how she and her colleagues signed pieces of paper on the drink counter.

Not only are the Buffalo baristas incredibly motivated, says Mr. Bensinger; they’re incredibly young. And while they may not look like stereotypical union workers of America’s past, they are a central force behind today’s rising pro-union sentiment. According to a Gallup Poll last September, public support for unions is at a 17-year high, with Americans between the ages of 18 and 34 more likely to approve of unions than their older peers.

But it’s not just young people’s left-leaning politics that’s causing a “tectonic shift in workplace power relations,” as Nelson Lichtenstein, director of the Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara, puts it.

The uptick in union support is part of a larger national shift toward worker empowerment, say experts, fueled by a pandemic economy that has blended strong consumer demand with a shortage of workers for many public-facing service sector jobs. In 2021, quit rates are the highest they have been since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started keeping track in 2000.

Whether it’s pandemic parenting challenges, increased unemployment benefits, or heightened concerns over workplace safety that are keeping workers away, help is wanted. And that means those still working have more leverage to demand higher pay, improved conditions, and better work-life balance.

“You hear about all these businesses who are struggling to keep people hired, and that has played a part [in our decision to unionize] because it shows that it is harder for them to replace us,” says Michael Sanabria, a Buffalo barista who has worked for Starbucks for almost four years. “So please, really listen to our voice, because we don’t want to go work elsewhere.”

“A lightbulb moment”

Almost 6 million restaurant workers lost their jobs during the first few months of COVID-19 lockdowns, says Saru Jayaraman, president of One Fair Wage and director of the Food Labor Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley. Of those, 63% were unable to qualify for unemployment benefits because their pre-tip wages were too low.

“That was kind of a lightbulb moment for a lot of these workers,” says Ms. Jayaraman. “This is the first time in 150 years that you’re seeing this level of rejection by workers of a subminimum wage.” She adds, “That is new, and that is powerful.”

Still, it remains to be seen whether workers will capitalize on the current climate in a way that cements long-term change. Many may accept one-time bonuses and other short-term incentives instead of pushing for broader and more permanent gains, such as by organizing unions or campaigning for higher minimum wage laws.

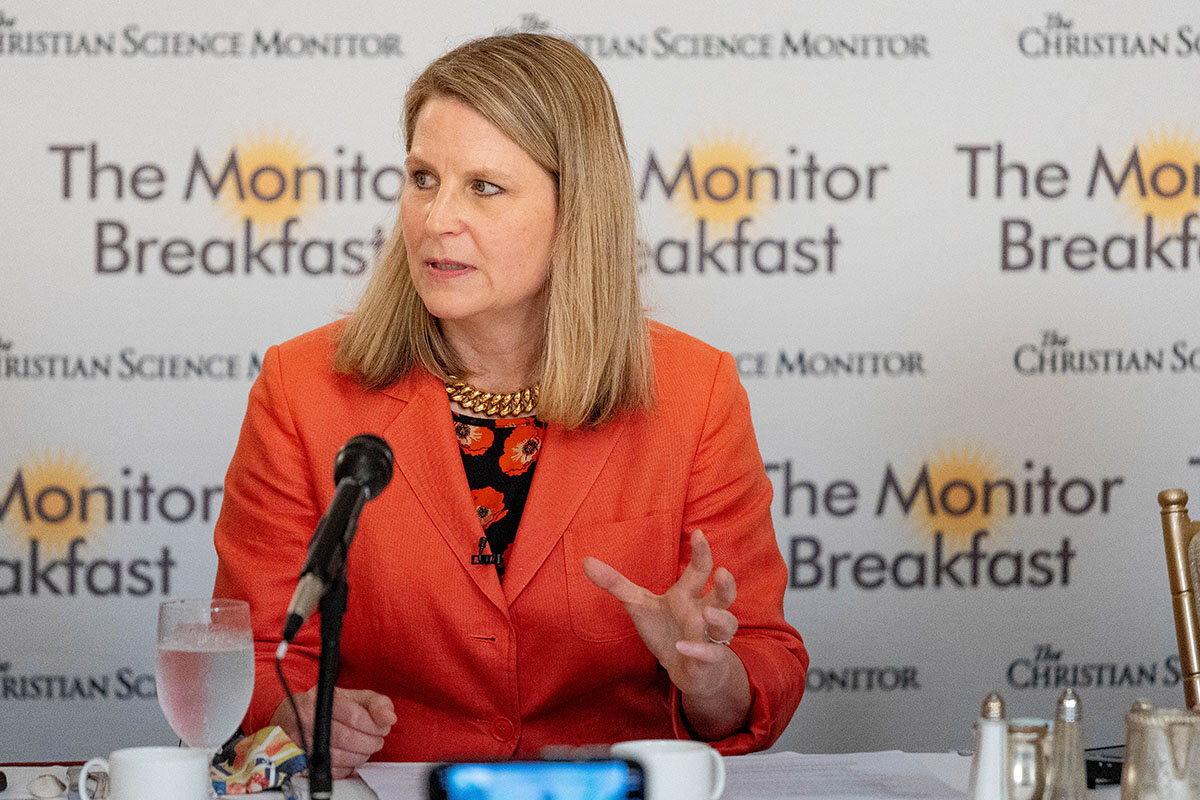

That’s something Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO, which represents more than 12 million workers, warned against at a Monitor Breakfast earlier this week. She referenced a 2018 protest at Google, when 20,000 workers walked off the job in response to how the company had handled sexual assault allegations. The protesters sent Google a list of demands, but not all of them were met.

“Things have just gone back to the status quo [at Google] because they didn’t have an organized way, with the enforcement of the law behind them, to sustain it,” says Ms. Shuler. “Folks are starting to connect the dots, especially in industries that traditionally haven’t had unions. ... We must meet this moment by building a modern labor movement.”

That also means taking advantage of the moment politically, adds Ms. Shuler, especially when Washington has “the most pro-worker administration in history” under President Joe Biden. The AFL-CIO has campaigned for the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would nullify right-to-work laws in place in several states and prohibit employer interference in union elections.

Although the PRO Act passed the House in March, it stands little chance of passing the closely divided Senate. Still, the pandemic has done much to further pro-union sentiment outside Washington, where many of the country’s “essential workers” have felt underappreciated.

“Starbucks has been saying we are the heroes on the front line. We got vaccines earlier because we are ‘essential workers,’” says Ms. Brisack, the barista at Buffalo’s Elmwood Avenue branch. “But if we are essential, then it should also be essential to give us a voice in making these decisions that affect us.”

Another social justice cause

A 2020 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics found sales and food-serving occupations have some of the lowest unionization rates of any occupational group. Simultaneously, these workers have been among the hardest hit by the pandemic over the past year and a half, creating what one Buffalo barista calls “a perfect storm.”

At the eye of this storm are young workers, who are more likely to be employed in these nonunionized, at-risk occupations. Last year, unemployment rates for Generation Z, or those under the age of 24, rose to almost 25%.

“My generation, I think we screwed everything up,” says Mr. Bensinger, a baby boomer. “Gen Z is smart, underappreciated, and underpaid.”

Although he admits to not always understanding the memes circulating around the office, Mr. Bensinger says young people are “leading an incredible resurgence for the labor movement” by including labor rights as another social justice cause worth fighting for.

“We work for a company that touts itself as a leader in supporting [Black Lives Matter] and LGBTQ rights – but they union-bust,” says Ms. Brisack of Starbucks. “There is even less acceptance for that [now] than there has been.”

Still, not all young workers taking advantage of the current economy to demand better conditions say a union is the answer.

Raven Harper, for example, a millennial tech worker in Nashville, Tennessee, hadn’t been searching for a new job for long when she received three offers all at once. So she decided to be clear with the company she was most interested in about her wants in terms of salary, health benefits for her children and her husband, and paid time off.

She says she got her new employer to agree to it all, without the help of a union.

Ms. Harper previously worked for a company with a union, and while she appreciated it sometimes, she doesn’t think she would join one again if she had the choice. She says much of the current shift toward workers’ rights is thanks to her generation’s attitude toward work and unwillingness to settle.

“The generation that I’m a part of, we’re movers and shakers,” says Ms. Harper. “We don’t accept the bare minimum, or we’re trying not to. We’re trying to do better and see better for ourselves.”

Back in Buffalo, Ms. Brisack and Mr. Sanabria also credit their generation’s values for helping their fledgling unionization campaign, which they say has been marked by a strong camaraderie.

“We are all working together for one cause,” says Mr. Sanabria, “and that cause is us.”

Staff writer Erika Page contributed to this report.