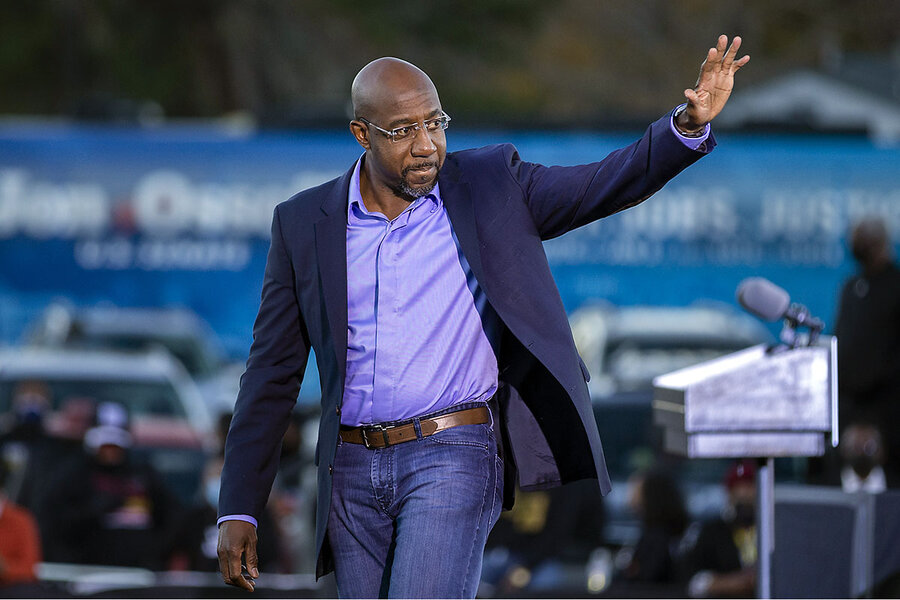

Sign of a changing South: Raphael Warnock joins Senate

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga.

The historic nature of the Rev. Raphael Warnock’s election victory this month, the first time that Georgia had elected a Black senator, made headlines across the nation.

It also got the attention of the children living in Kayton Homes, a weathered two-story brick housing project in Savannah, where Mr. Warnock, a Democrat, grew up, one of 12 children. Terriyonna Blige, an energetic Black tween, points to the balcony of an apartment where she says Mr. Warnock lived as a child. “He won, right?” says Terriyonna. “Over 50%.”

Mr. Warnock’s win “shows that it doesn’t matter where you come from, it only depends on where you’re going,” says teenager Sharefe Morgan.

Why We Wrote This

Many have called Raphael Warnock’s historic victory a sign of the changing South. That includes children in Savannah’s Kayton Homes, where Mr. Warnock grew up. It “shows that it doesn’t matter where you come from, it only depends on where you’re going,” one says.

As the children understood, the elections of Mr. Warnock, a Baptist preacher, and fellow Democrat Jon Ossoff, a 30-something Jewish filmmaker, thrust Georgia into the limelight. Their come-from-behind runoff victories on Jan. 5 brought the Senate to a 50-50 split, with Vice President Kamala Harris casting tie-breaking votes and giving control to the Democrats. The next day, a mob of right-wing extremists incited by former President Donald Trump sought to subvert the voters’ will at the U.S. Capitol. The two new senators from Georgia were sworn in by Vice President Harris Wednesday, along with her replacement Sen. Alex Padilla of California.

Usually clad in a light-colored button-down shirt and fashionable rimless glasses, Mr. Warnock comes off as a thoroughly urbane Georgian. During the campaign, he ran lighthearted ads preemptively debunking opposition attacks by insisting he doesn’t hate puppies. He ran as an unabashed liberal in a conservative state, embracing a social justice gospel that has anchored the Black church for over 200 years.

As demographic shifts, a pandemic, and a divisive presidency coalesced, the election victories in Georgia have revealed an American South where Black and Jewish politicians can win on their own unabashedly liberal terms, complicating the path forward for Republicans in a region once known as the Solid South. Those demographics bode ill for Republicans in this and other Southern states that are attracting hundreds of thousands of Black and white transplants who bring more progressive mindsets.

“It is a multiracial and progressive coalition that seems to be bolstered by African American voters and white liberals in and around Atlanta,” says Jason Sokol, author of “The Heavens Might Crack: The death and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.”

That means Mr. Warnock “is free to embrace his work on social justice and can actually win votes because of it rather than worrying about whether he’s going to lose white moderates because of it,” he says.

A rebuke by Black voters

It’s been only 50-some years since passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1964, and Jim Crow is well within living memory. In his victory speech, Mr. Warnock thanked his mom, whose “82-year-old hands picked somebody else’s cotton” and has now cast a vote for her son to be elected as U.S. senator.

While the overt terror tactics and legal framework of white supremacy has ended, last year’s murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, Georgia, was likened by many here to a modern-day lynching. Three white men chased the young Black jogger down and killed him after presuming, falsely, that he had committed a crime in the neighborhood. The three men have been charged with murder and other felony charges. And on the day after the runoff votes, as Mr. Warnock’s supporters celebrated his triumph, a man carried a Confederate battle flag through the U.S. Capitol as part of the pro-Trump invasion.

Those memories and recent events inform Mr. Warnock’s victory, effectively a rebuke by Black voters to white nationalism.

Until now, the legacy of Georgia’s county-unit voting system, which overweighted rural votes before it was declared illegal, has kept the rolls of statewide constitutional offices populated by white Georgians. In the meantime, Black politicians have built power bases in Atlanta and other cities.

“A lot of folks are still around that remember a time when it wasn’t even taken seriously that a Black candidate could win statewide,” says Charles Bullock III, an expert on Georgia politics at the University of Georgia, in Athens. “There was this notion that Blacks can be competitive, but still pay a racial tax that gets assessed by the electorate. That’s no longer the situation here in Georgia.”

The Trump factor

Before this month’s victories, Democrats had a 0-8 record in Georgia runoffs. Moreover, they had not won a statewide race since 2002 and hadn’t won a Senate seat since 1992, when Bill Clinton won the state’s electoral-college votes.

Together, all four candidates raised nearly half a billion dollars to fuel their campaigns, highlighting the national stakes to control the Senate.

One factor in these runoffs, that may not be repeated in future elections, is President Trump’s smearing of Georgia’s Republican election officials as “enemies of the state” for their refusal to overturn Mr. Biden’s legitimate win. That controversy emboldened Democrats – especially Black ones who voted in record numbers – and depressed the vote among white conservatives.

Take northwest Georgia’s 14th Congressional District. In November, it elected Marjorie Taylor Greene, a QAnon conspiracist and fervent Trump supporter, as its House representative. Trump appeared in the district the night before the election. But 50,000 fewer voters turned out there on Jan. 5, even as Mr. Warnock and Mr. Ossoff ran up larger margins in urban counties compared with the general election.

The election results suggest that “the Republican Party has hit its peak and is now seeing a very rapid decline in Georgia,” says Mr. Bullock, author of “The Rise and Fall of the Voting Rights Act.” “They’ve run out of white voters.”

The Republican incumbent senators, Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue, two of the richest lawmakers in Congress, largely gave up any appeals to Georgia’s diverse suburbs and tethered themselves fully to Mr. Trump and his rural base. They depicted Georgia as a firewall against socialism to “save America.” Senator Loeffler’s campaign called Mr. Warnock a Marxist who had impugned America from the pulpit.

Her campaign showcased the Republican Party’s brand of racial insensitivity, says Emory University political scientist Andra Gillespie. “Attacking Warnock’s faith in highly racialized terms only reinforced the idea that the Republican Party has a serious problem with race, which means it has a serious problem in the African American community,” she says.

Faith as a shield

While Republican candidates tried to make Mr. Warnock’s preaching a lightning rod, his faith may have proven a shield.

Mr. Warnock, the senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. once preached, is part of a Black church tradition that finds meaning in bearing witness to a social gospel of light and righteousness. That tradition has given joy and hope to oppressed Americans, even while engaging in uncomfortable truth-telling about institutional inequalities.

Jesus, Mr. Warnock said in an interview nearly 20 years ago, “was an extremist for love, truth, and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation, and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.”

Born to two Pentecostal pastors, Mr. Warnock spent his formative years in Savannah. After graduating high school, he followed King’s example, earning a theology degree at Morehouse College, and then, taking over as senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in 2005. One of his parishioners was John Lewis, the late Democratic representative and civil rights icon.

Mr. Warnock was arrested during a protest in 2014 in support of expanding Medicaid in Georgia. Until last year he was the chair of the New Georgia Project, the voter registration organization founded by Stacey Abrams that many credit for boosting Black turnout at Georgia’s elections.

In winning the seat, he becomes the first popularly elected Black Democrat from a former Confederate state to hold a U.S. Senate seat. He is also the first African American politician to win election to the U.S. Senate on the strength of a majority-Black coalition.

Mr. Warnock took that unapologetic message to the voters this fall – and polled so strongly that he triggered a runoff. It resonated as winter came, says the Rev. Dwight Andrews of Atlanta.

“The social gospel movement of the late 19th century was about workers, giving workers a way to safety and education,” says Mr. Andrews, senior minister at First Congregational Church in Atlanta. “It’s not about Black and white. It’s about uplifting the least of these in the world. That means these messages go well beyond race ... but it has unfortunately been racialized.”

His election, however, marked a breakthrough, Mr. Warnock argued in his acceptance speech.

“This is the reversal of the old Southern strategy that sought to divide people,” he said. “In this moment, we’ve got to bring people together in order to do the hard work. And I look forward to doing that work.”