Society commonly describes a church as a place – a location of worship. The Christian Bible describes it as something more. “Church” or its translation in the Greek, ecclesia, denotes a group of believers.

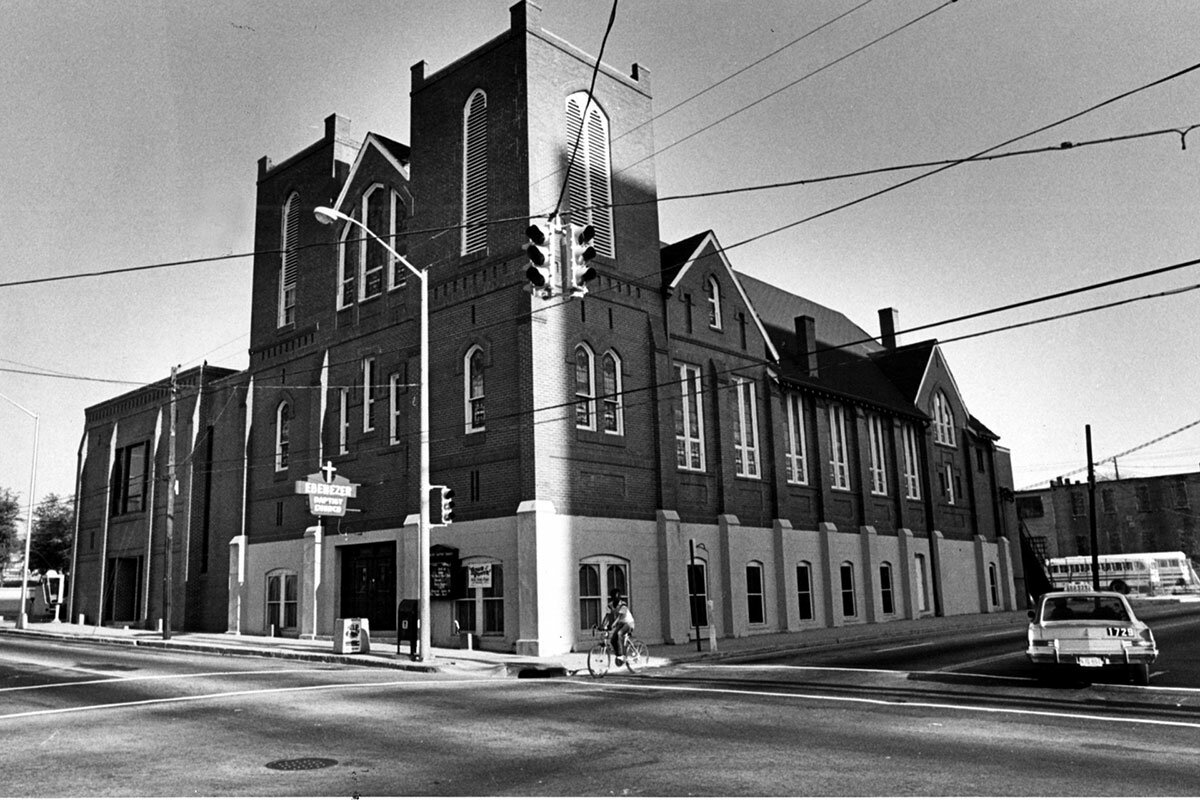

Whichever definition one prefers, in the case of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, its place in history is secure.

It’s in this place where we find the Rev. Raphael Warnock, who has been pegged as “anti-American” for his political views in the face of a hotly contested Senate race in Georgia.

In recent weeks, Mr. Warnock has come under fire from his opponent, Sen. Kelly Loeffler, and the Republican Party for what they deem to be “radical” comments that he made in Ebenezer’s pulpit in 2011: “America, nobody can serve God and the military. You can’t serve God and money. You cannot serve God and mammon at the same time,” he said, invoking Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. “America, choose ye this day whom you will serve. Choose ye this day.”

Both the church and Mr. Warnock have faced racist and threatening calls ahead of the Senate runoffs Jan. 5., the church said in a statement.

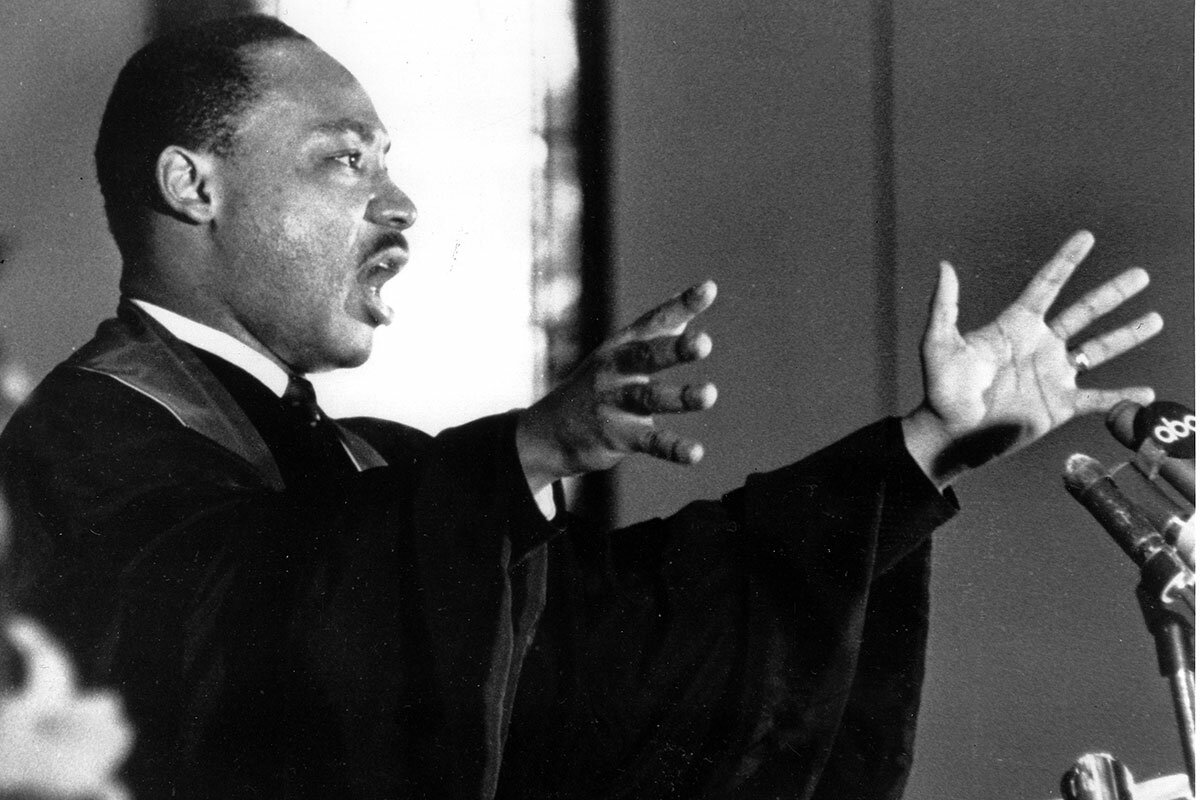

Such a designation for Mr. Warnock, Ebenezer’s current pastor, is as ironic as it is untrue – and not unprecedented when it comes to prior Ebenezer pastors. One year before his assassination, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. offered a commentary in New York City titled “Beyond Vietnam.” Like Mr. Warnock, he would be strongly criticized and rebuked for his message:

... As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked, and rightly so, “What about Vietnam?” They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.

... Now it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war. If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read “Vietnam.” It can never be saved so long as it destroys the deepest hopes of men the world over.

It is in these moments of expression – of freedom – that we not only see the legacy of outspoken Kings. We also see the legacy of “America’s Freedom Church.”

The church, with a name that means “stone of help,” was founded in 1886 by a freedman, John A. Parker, less than a decade after the end of Reconstruction. Imagine the challenges that come with founding a church in the midst of race-related violence and the genesis of Jim Crow, and the conviction that it would take to do so. In Ebenezer’s case, it took the courage of a man born into – and emancipated from – slavery to accomplish the task.

When Parker died in 1894, Alfred Daniel Williams became the church’s pastor. It was under Williams’ leadership that Ebenezer grew in membership and stature, and also during that time when it found a familiar home on the corner of Auburn Avenue and Jackson Street.

Who could have known the power of the Williams’ lineage at that time? Who could have known that the next two pastors – Williams’ son-in-law, the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., and Williams’ grandson, Martin Luther King Jr. – would not only make the King name a household name, but also the church’s name as well?

Ebenezer’s history is a triumph of community and conviction. Mr. Warnock explores the duality and responsibility of the Black church in an excerpt from his 2014 book, “The Divided Mind of the Black Church”:

What is the true nature and mission of the church? As a community formed in memory of Jesus Christ and informed by the gospels, what is that makes it a faithful and authentic witness, and what exactly is it called to do? Indeed, all Christian communities must ask and try to answer that question. ... The question has itself a distinctive resonance when the church is one built by slaves and formed, from its beginning, at the center of an oppressed community’s fight for personhood and freedom. That is the history of the Black church in America and the theological prism through which any authentic inquiry into its essential mission must be raised.

He continues with an excerpt that reads like prophecy:

In important ways, it is this enduring concern for the relationship between black religion and black resistance – piety and public witness – that helps to account for the origins and development of black theology. From the very moment of its emergency from the fiery tumult of riot-torn cities and heated national debate regarding the meaning of a new and rising black consciousness, captured in the expression “black power,” black theology has been careful to situate its own self-understanding within the larger historical narrative of black religion and black resistance.

Ebenezer’s history and commentaries suggest that it is a “radical” church, but not in the sense that Senator Loeffler and the GOP suggest. Ebenezer is radical in its sense of survival. It has seen the viciousness of Jim Crow. It has seen its native son assassinated. It has housed the funerals of King, John Lewis, and Rayshard Brooks.

And yet, it is renewed – and not just because of the work of the National Park Service. It is renewed because Ebenezer once again has met the challenge of a ministry that accepts the “double-edged sword” of theology and ideology.