Biden, Sanders, and the struggle for the Democrats’ future

Loading...

So far, watching the 2020 Democratic primary process has been like riding a world-class roller coaster, full of wild swings, sudden climbs, and stomach-churning plummets.

And like a spin around Cedar Point amusement park’s “Steel Vengeance,” it has ended up back where it began: with former Vice President Joe Biden as the frontrunner and candidate with the clearest path to winning the nomination.

But don’t unbuckle yet. Sen. Bernie Sanders still has money, organization, and a devoted following on his side. Democratic Party rules, which award delegates on a proportional basis in each state, favor a close race.

Why We Wrote This

Behind the personal rivalries and rising and falling fortunes that have narrowed the field this presidential primary season, there’s a fundamental clash lining up between the Democrats’ revolutionary and moderate wings.

There’s a debate scheduled for March 15 that will be essentially one-on-one. Events held a day or so prior to a vote have seemed extraordinarily influential this primary season.

Nor did Super Tuesday solve the basic division within the Democratic Party, which pits Senator Sanders, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and other progressive revolutionaries against moderates who wish to restore Obama-era priorities. That’s a split so fundamental it could cause intramural friction for years to come, no matter who wins the party’s 2020 nod.

While the restoration wing of the party seeks a return to political norms, civility, and respect for all after years of growing polarization, the progressive wing argues that the United States needs bolder, sweeping changes to everything from health care to climate change.

“I suspect everybody will get together and try to make sure we get rid of Trump. If that happens, we will postpone this conflict a little bit. But it will come back,” says Bill Carrick, a longtime Democratic consultant in Los Angeles.

From zero primaries to 11

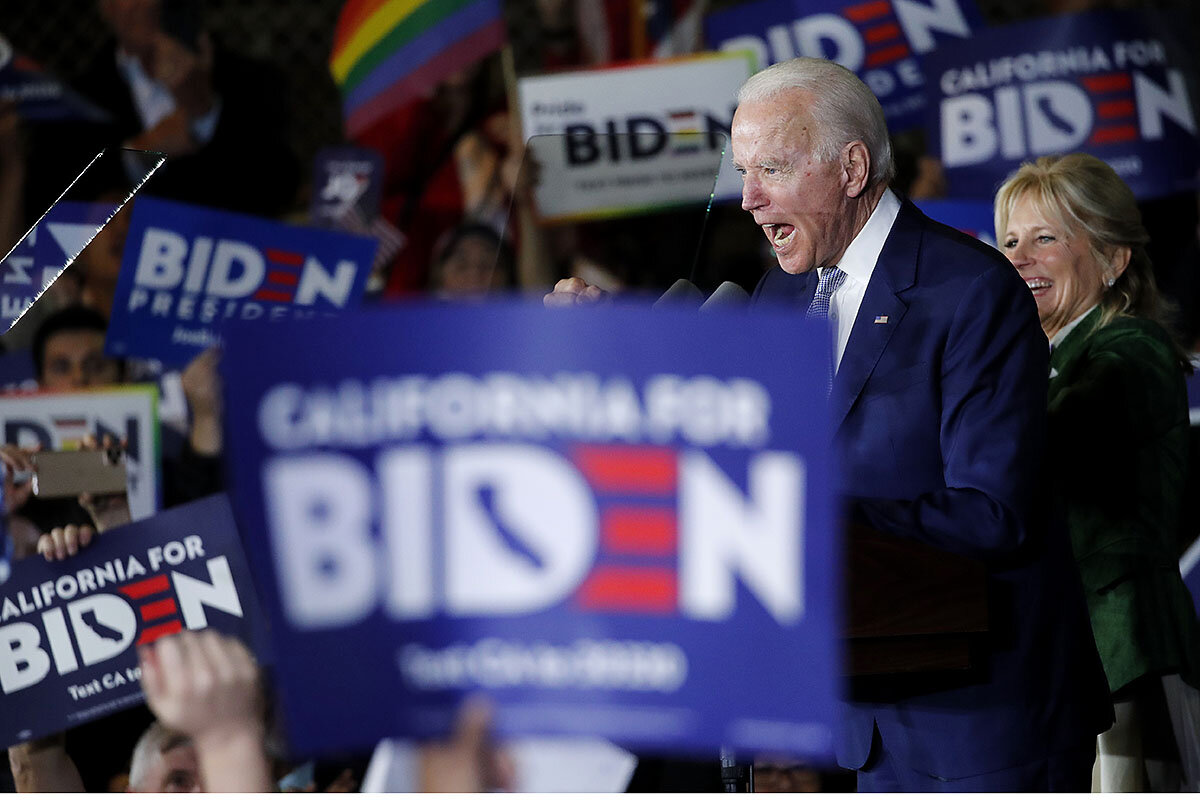

Still, by almost any measure, Super Tuesday 2020 was a stunning uplift for an American politician who has been a fixture in Washington since winning a Senate seat in 1972, then served eight years as vice president, yet never before gained any momentum for his own burning presidential ambitions.

Joe Biden has run for the nation’s highest office three times. Before last Saturday in South Carolina, he had never won a primary. Now he has won 11. The other moderates in the race have dropped out and endorsed him.

He currently leads in delegates, with an estimated 433, according to a mid-afternoon Wednesday estimate from The New York Times. Senator Sanders trails with 388.

Mr. Biden benefited from a sudden coalescing of center-left Democrats around his candidacy. With Mr. Sanders surging, these voters decided it was time to settle, not moon after political crushes. African-American voters were crucial to the Biden coalition, which included substantial numbers of working-class whites and college-educated women.

Biden voters interviewed in Virginia’s 7th Congressional District, won by Democratic Rep. Abigail Spanberger in 2018 after 38 years of Republican representation, spoke of a number of reasons why they supported the former vice president. But one thing was on top of many of their lists.

“I just want him to beat Trump,” says Amy Davis, an African-American stay-at-home mom from Culpeper.

Ms. Davis adds that she also thought Mr. Biden did a good job as vice president.

“He impressed me when he worked under Obama,” she says.

Coming to Biden

Some Biden supporters said they had switched from other candidates.

Pat Carl, a retired white man serving as a poll watcher with the Spotsylvania Democrats, says originally, he liked Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who withdrew from the race and endorsed Mr. Biden earlier this week.

But Mr. Carl says he’s confident that a Biden administration would have a place in it for Senator Klobuchar. And as a former Republican, he’s attracted by Mr. Biden’s ideological position in the Democratic Party.

“I’m a moderate kind of person,” he says.

Several Virginia Biden voters volunteered that they’d cast a ballot for President Donald Trump in 2016. They’d believed in his “Make America Great Again” slogan.

But they’ve found his behavior as president off-putting.

“Now he’s just lashing out at everyone, firing his own staff. I’m so disappointed in him,” says Alan Burnham, a white male school bus driver.

Given all the uproar over Mr. Biden’s sudden reemergence as the Democratic front-runner, it is easy to forget that only about one-third of the total number of pledged state delegates to the party convention in Milwaukee have been chosen. There is plenty of time remaining for a Biden stumble, or a Sanders rally.

Six states hold primary votes March 10, including the crucial Rust Belt state of Michigan. Four more states vote March 17, including Florida and Ohio.

Biden’s flaws; Sanders’ strengths

As a candidate, Mr. Biden has flaws. That is part of the reason why he struggled to raise funds and attract voters in the primary season’s initial contests.

On the stump he is prone to garbled speech and other verbal miscues – at his victory appearance Tuesday night, for instance, he mistakenly identified his wife as his sister, and vice versa. (He quickly corrected the error.) He’s been known to run on, and on. Sometimes he gets names mixed up. Given his length of service in Washington, he’s not exactly an exciting new face.

“I don’t think he’s a weak candidate. I think he’s got some weaknesses as a candidate,” says Garry South, a longtime Democratic consultant based in Los Angeles.

But Democrats will start to look at Mr. Biden and see that “at the end of the day, that’s part of what makes him authentic,” Mr. South says.

Meanwhile, Mr. Sanders has strengths. His campaign is flush with cash, and his ability to raise small dollar donations online remains unparalleled. Many of his supporters are devoted in a way that Biden voters don’t appear to be. His rallies draw tens of thousands of fans to hear him excoriate billionaires and corporations and promote Medicare For All and free tuition at public colleges and universities.

For all the attention given to Mr. Biden, the two men remain almost tied in the currency that matters most, delegate strength, Senator Sanders pointed out in an appearance at his Burlington, Vermont campaign office Wednesday.

“What this campaign … is increasingly about is, which side are you on? Our campaign is unprecedented” when it comes to grassroots support, Mr. Sanders said.

In Virginia, primary voters who opted for Senator Sanders stressed his appeal to young people, and how his proposals went to the heart of their concerns.

Amber Seagrave, a young white woman with pink hair who works as a stylist, says she voted for him in part because of his proposals to eliminate student loan debt.

“I’m going to be late on my student loans again this month,” says Ms. Seagrave. “I had to drop out of college because I couldn’t pay for it.”

Limits to the division

The Democratic nightmare is that the animosity between the Sanders and Biden camps will extend past the convention, and that the loser’s side will sit on its hands and have a lower turnout rate for the general election.

“Over the next month or so, we will see a lot of animosity, anger, resentment. It will look bad and end up feeling pretty similar to 2016,” when bad feeling developed between the Hillary Clinton and Sanders campaigns, says Prof. David Barker, director of the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies at American University.

But Professor Barker says there are several reasons why this division won’t end up being as consequential as it was four years ago.

For one thing, President Trump is an incumbent both sides want very much to oust. For another, Joe Biden is not Hillary Clinton. Ms. Clinton generated antipathy from both Republicans and the Democratic left wing. Mr. Biden perhaps doesn’t produce that level of animosity.

“The thing about Biden now is that while he doesn’t excite the young progressive left, he also doesn’t inspire the same level of loathing. There seems to be some level of warmth for the guy,” says Professor Barker.

Francine Kiefer contributed to this story.