Can Democrats win back Obama-Trump voters? Dubuque, Iowa, may offer a clue.

Loading...

| Dubuque, Iowa

Cathy Mauk Dickens has lived in Iowa for more than four decades – but until last year she never really knew what a caucus was.

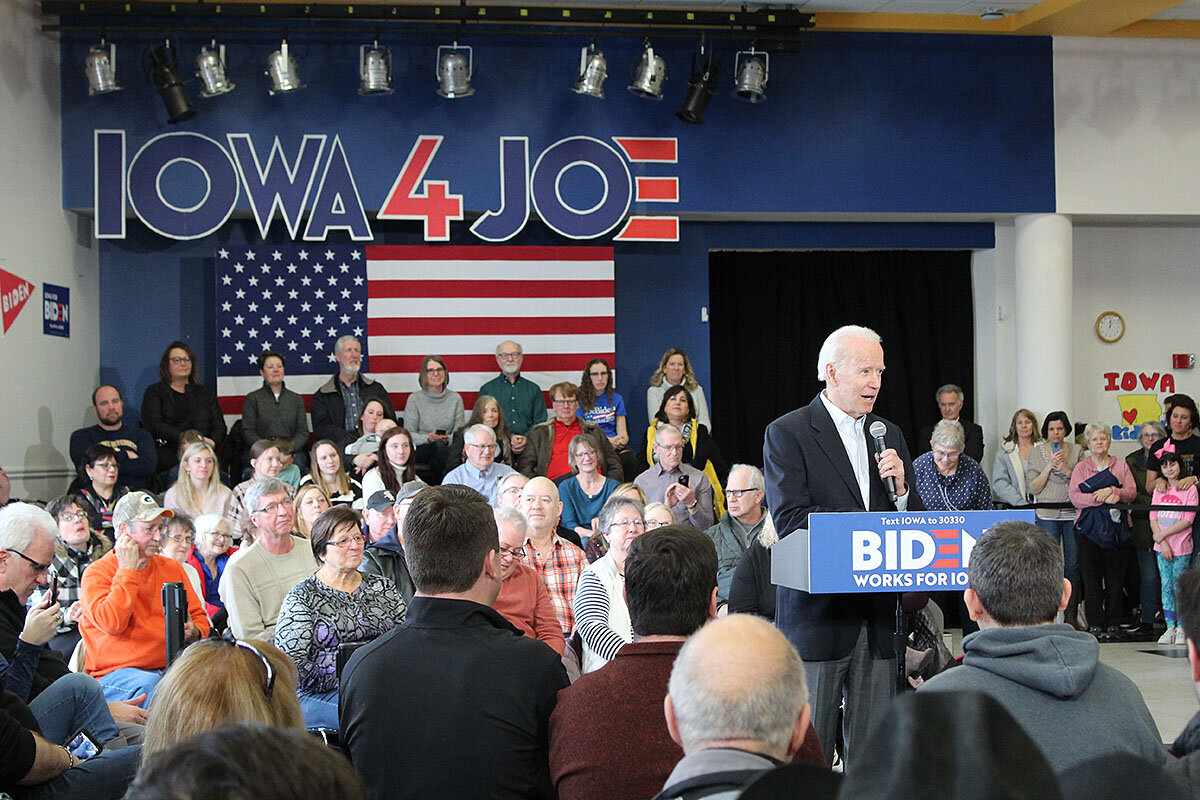

Now, she’s a precinct captain for former Vice President Joe Biden, preparing to participate for the first time in an election event she and other volunteers milling about the campaign field office see as crucial for American democracy.

Standing by a table of pizza and potluck dishes that have cooled off since Jill Biden arrived to address the crowd, Mrs. Dickens explains that she feels partially responsible for what happened in 2016.

Why We Wrote This

As Iowans kick off the Democratic nomination contest, we take a closer look at a county that flipped from blue to red in 2016 – and ask if it marked a momentary burst of frustration or a long-term shift in political preferences.

It was she who took her sister to a Trump rally as candidates made the rounds through Iowa, host of the first-in-the-nation caucuses. Her sister became a devout follower – and still is, praising the president for his patriotism, support for the military and law enforcement, stance against illegal immigration, and role in creating the lowest unemployment in decades.

It’s not until 15 minutes into the conversation that Mrs. Dickens quietly reveals that she, too, voted for Donald Trump after having twice supported Barack Obama – thinking a businessman could boost the economy.

“He hadn’t shown his colors yet,” she says. “Right away, when I saw the lying … I felt so bad.”

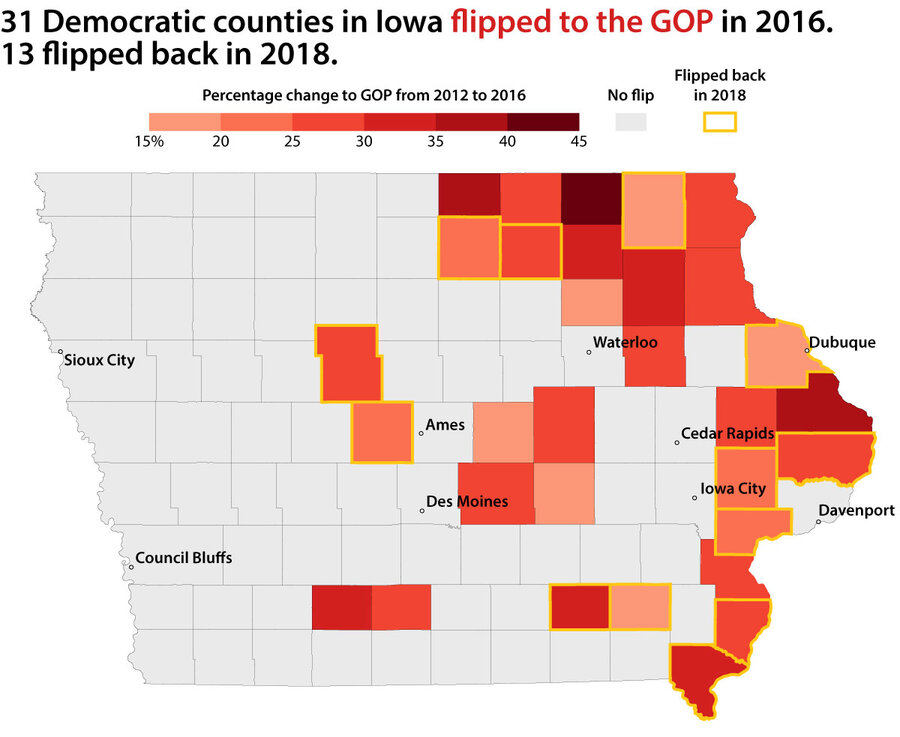

Thanks in part to voters like Mrs. Dickens and her sister, Dubuque County followed the rest of eastern Iowa in 2016 and swung red for President Trump after years of reliably voting Democratic. Iowa as a whole also went for Mr. Trump, after twice awarding its electoral votes to President Obama.

Some Democratic strategists have lately suggested the party shouldn’t bother competing for Iowa’s six electoral votes in November – viewing its rural, graying profile as a harder lift than Sun Belt states with their booming young and immigrant populations.

Yet all the focus on “Obama-Trump voters,” and whether Democrats have lost them for good, tends to overshadow other key factors behind Iowa’s flip to the GOP – including far lower turnout in 2016. While Mr. Trump got 7% more votes than Mitt Romney in 2012, the bigger storyline for Democrats was that Hillary Clinton underperformed Mr. Obama’s vote tally by 22%.

In other words, what appeared on blue- and red-checkered maps of Iowa as a dramatic shift toward Republican values may have been more based on personality than principle – including dislike of Mrs. Clinton and the novelty of an anti-establishment candidate who wasn’t afraid to call it as he saw it.

“Hillary was within walking distance of my house in 2016, and I didn’t even bother going to see her,” says Ed Gansemer, a lifelong Dubuquer and Democratic voter. Although Mr. Gansemer, a retired electrician at the local John Deere plant, voted for Mrs. Clinton in the end, others couldn’t overcome their antipathy, casting their ballots for a third-party candidate or staying home altogether.

More than five dozen interviews with residents here, conducted everywhere from Target to town halls, suggest – for now – a resurgent support for Democrats in Dubuque, the most populous county in northeastern Iowa that voted for Mr. Trump in 2016 and then for a young Democratic congresswoman in 2018. At the very least, Dubuque offers a key test for Democratic candidates – since electoral success here could portend similar results in critical swing states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, where white working-class voters may make the difference.

While many Democrats here express distaste for Mr. Trump, they also raise questions about whether a candidate as liberal as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren could win come November.

“We’re afraid if Sanders gets it,” says Linda, a middle-aged woman who declined to give her last name, at a Joe Biden town hall at Clarke University in Dubuque the day before the caucuses.

“Republicans who I know who don’t like Trump any more – they wouldn’t vote for a socialist,” agrees her friend Mary.

Wayne Demmer, a farmer who raises cattle, hogs, and grain outside Dubuque, is nearly certain the county will go blue in 2020 – unless the nominee is Senator Warren or Senator Sanders, whose proposals like “Medicare for All” and free college tuition may not resonate with the work ethic here.

“It does scare me if we end up with one of these giveaway candidates,” says Mr. Demmer, a former county supervisor attending Tom Steyer’s town hall in Dubuque on Friday. “People in Iowa still go out and work for what they have. And that’s the concept of all of rural America. We live by the saying don’t give someone a fish, give them a fishing pole.”

A turnaround story

Dubuque is not your stereotypical Midwestern Trump stronghold, a declining industrial city struggling to reinvent itself. It already has. It went from having the highest jobless rate in America (23%) in the early 1980s to just 1.9% last year, though in poorer neighborhoods it’s twice that and the poverty rate is nearly 12%.

Today, the city of nearly 60,000 is growing, and its downtown – nestled at the base of bluffs along the ice-gray Mississippi – features breweries and boutique yarn shops, art galleries, and cafes selling avocado toast and almond milk lattes. Down by the river, refurbished mill buildings now house condos and lofts, some with waiting lists.

The first city in Iowa to be settled, by an eponymous Quebecois explorer, Dubuque is also a Catholic stronghold that’s home to three colleges and several seminaries. It counts among its most famous residents Olympic medalists, the Hamilton of Booz Allen Hamilton, and a rear admiral in the U.S. Navy who surveyed the Amazon and helped capture Guam.

It is the county seat of one of 31 counties in Iowa that voted for Mr. Obama and then Mr. Trump, the most of any state in the country. The president won Dubuque by just 1.2% – becoming the first Republican presidential candidate to win over the county’s residents since Dwight Eisenhower. In 2018, Democrat Abby Finkenauer, the 29-year-old daughter of a union welder, won them back in her bid for the U.S. House of Representatives.

Lindsay James, a Democratic state representative from Dubuque, says the main issues she hears about from constituents are health care, jobs, and good schools.

“They’ll vote for whoever is speaking to those issues, regardless of party lines,” says Ms. James, adding that she’s talked with numerous Republicans who are caucusing on Monday or planning to vote for the Democratic nominee in November.

The front-runners in the Democratic field have spent considerable effort wooing these voters, making the trek out to this eastern outpost on the Mississippi, some three hours from Des Moines. This past weekend marked the fourth trip to the city for both Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden, and Andrew Yang’s third in just six weeks.

“I’ve never voted for a Democrat before. Yang is the only one I’d vote for,” says real estate agent Jay Schiesl at a Yang event last Thursday in Dubuque, where every seat was claimed and late arrivals had to stand in the back. “This is the first time I’ll ever caucus. I have to put a ‘D’ next to my name to be able to caucus. Do you know how hard that’s going to be?”

Senator Sanders, Senator Warren, and Amy Klobuchar each made it three times before the impeachment proceedings constrained their ability to campaign in the final weeks before the caucus.

“Contrast that with [Julian] Castro,” says Steve Drahozal, chair of the Dubuque County Democratic Party, who liked the former Housing and Urban Development secretary’s positions but lamented that he – like others who have since been forced to drop out – didn’t recognize the importance of this part of the state. “He could not find his way out of central Iowa.”

Thanks in part to fresh faces like Mr. Yang, who appears to have attracted a lot of new folks beyond the usual core Democrats, engagement is way up this year, says Mr. Drahozal. The county party’s cash reserves have more than doubled, and the email list has grown by close to 50%.

“My own brother, who is 46 years old, has never caucused and he’s going to caucus for the first time this year,” he says.

Nathan Thompson, Democratic chair in Winneshiek County – the only other Trump county that Representative Finkenauer won back – echoes that. Crowds at Democratic events have increased by about a third, and the county party’s financial situation is about twice as good as before, he says. Mr. Buttigieg drew nearly 1,000 people last summer.

“The story over and over in Iowa with Democrats losing is, we fail in the rural areas,” he says. “The Warren and Buttigieg campaigns have made a real effort to get outside of [the county seat of] Decorah and hit some of those rural doors.”

“You can’t have missed how important this election is”

Emily and Rick Reeg are among the more than 700 people who turned out for a Buttigieg town hall in Dubuque this weekend, exceeding the expectations of the campaign, which ran out of stickers for attendees checking in.

Ms. Reeg, a first-grade teacher, is all in for Pete – a precinct leader who likes his “honesty and integrity.” Her husband, a former business owner who voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, is more hesitant. Having lost a cousin who was killed by a suicide bomber in Iraq, he says his first priority is support for the military.

“That’s big for a lot of us,” says Mr. Reeg, who is deciding between Mr. Biden and Mr. Buttigieg, a Navy Reserves intelligence officer who served seven months in Afghanistan.

“I like a lot of Trump’s policies, to be honest, especially with foreign policy,” he says. “He’s willing to stay in communication with Putin and North Korea. We can’t just box them out like Obama. But Trump’s mouth,” he adds, shaking his head.

A Buttigieg campaign worker comes around with a fishbowl and white notecards, asking attendees if they would like to submit a question for the candidate. Mr. Reeg says yes, I’d like to ask him how he would respond to North Korea. As the campaign worker transcribes Mr. Reeg’s question, he clarifies that he specifically wants to know whether a future President Buttigieg would engage in a dialogue with Kim Jong Un.

Waiting in line to get in, Greg Orwoll, who has voted Democratic since the 1990s but couldn’t bring himself to cast a ballot for Hillary Clinton, is now repentant for having voted for a third-party candidate in 2016 (Jill Stein, because her name was first on the list).

“I thought [Clinton] was going to win. I just didn’t want her to have such a huge majority, which she thought she’d have,” he says. His wife, Shirley, leans in and whispers, “That’s why we lost!”

“You’re right, I know. Live and learn,” he says. “Personally, I’m supporting a ham sandwich on rye if it’s the Democrat.”

In 2016, he says, people weren’t passionate about the Democratic ticket – not like some Trump voters, who would have driven through a snowstorm to vote for their candidate. But this year, there’s passion on the Democratic side – and anger at Mr. Trump.

“I think that’s going to be really powerful in November,” says Mr. Orwoll, squinting in the bright sunlight reflecting off the snow. “Short of living under a rock, you can’t have missed how important this election is. You just can’t have missed that.”