Nostalgia 2020: Biden, like Trump, seeks to make America great again

Loading...

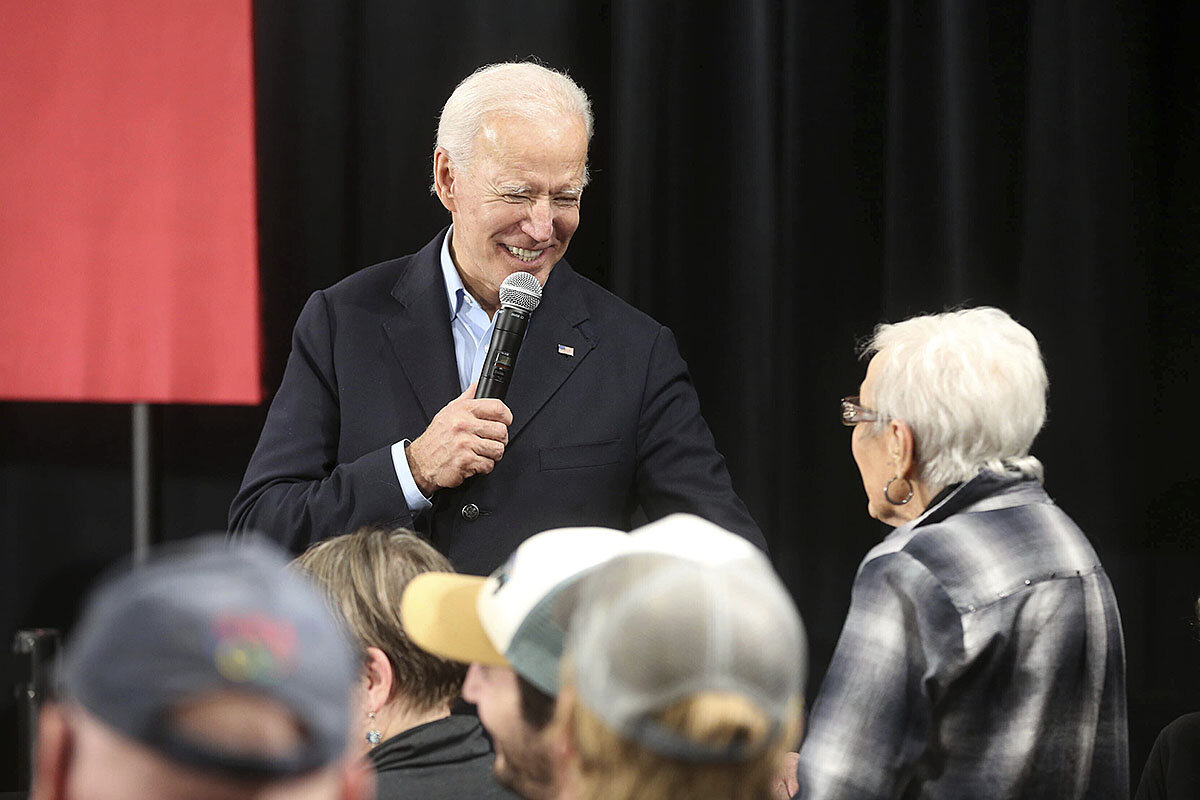

| Ames, Iowa

Throughout the Democratic primary, Joe Biden has argued he’s the candidate best positioned to beat President Donald Trump: the personable, been-there-done-that former vice president who’s moderate enough to appeal to independents in key swing states, and maybe even some Republicans.

But while casting himself as the president’s strongest opponent, Mr. Biden is also leaning into a message that is in some ways uncannily reminiscent of Mr. Trump’s own pitch in 2016 – his own variety of “Make America Great Again.”

Mr. Biden frequently speaks about reviving the middle class, which he calls the “backbone” of this country. The rest of the world is laughing at our once-respected nation, he tells voters, and only a change in leadership will restore America to the prosperous superpower it once was. On a recent bus tour in Iowa, the former vice president tells audiences what a shame it is that parents have to turn down the volume when the president appears on TV, for fear of their children hearing something nasty or inappropriate. A grandfather who uses words like “malarkey,” he jokingly apologizes that one side of the room has to look at his bald spot while he speaks.

Why We Wrote This

Remember when? Nostalgia often is a feature of ads, not political campaigns, which usually focus on the future. But Joe Biden, like President Donald Trump, tends to hark back to a “better time.”

Typically, political campaigns, especially presidential ones, focus on the future. Candidates offer fresh visions for the country, detailing innovative plans that would usher in a new, modern era of peace and prosperity.

But if Mr. Biden, who served in the Senate for more than three decades, wins the Democratic nomination, then the general election next year will feature two septuagenarians who spend a great deal of time talking about the past.

“Advertisers have been using nostalgia for decades,” says David Pizarro, a psychology professor at Cornell University. The Biden and Trump campaigns “are taking a page from a strategy that has worked well for, say, Coca-Cola.”

And while it may be less common in politics than themes like hope or change, Mr. Pizarro says it makes sense that campaigns today would employ nostalgia as a tool. Because despite “tons of things being way better than they ever have been” – such as longer life expectancies and improvements in education, for example – most people believe the country is worse off now than in the past.

“Part of the reason is that it’s easier now than ever to see all the bad things,” says Mr. Pizarro. “And because of that, it can really seem like things are getting worse and worse.”

The Obama connection

One difference between Mr. Biden’s and Mr. Trump’s use of nostalgia, says Mr. Pizarro, is the time period of their idyllic years. Mr. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” can mean different things to different people, but it clearly harks back to a time well before the Obama years. By contrast, Mr. Biden is wrapping himself in the Obama presidency – hoping to benefit from the warm feelings many Democrats hold for the former president, and the desire of many voters to return to the relative “normalcy” of that era.

In Ames, Iowa, for example, a woman asks him about improving Amtrak, but before she sits down, she tells the former vice president: “I back you because you worked well with Obama.”

The same goes for Wartburg College students Makayla and Sidney in Waverly. “For me, it was his connection with the Obama campaign,” says Makayla, explaining why she decided to come hear Mr. Biden speak.

To be sure, Mr. Biden is also careful to cast his vision forward. When a voter at Iowa State asks him how he plans to repair the damage from President Trump’s first term, he responds: “I’m not going to just repair. I want to build on what Barack and I built.” At a community college in Iowa Falls, he says he is “more optimistic than I’ve ever been” about the future of America.

“As Vice President Biden said, he’s running not to take us back to a fondly remembered past, but to build on our accomplishments,” says Bill Russo, the campaign’s deputy communications director. That includes beefing up Obamacare by adding a Medicare-like public option, reentering the Paris climate agreement while looking to “up the ante” on climate change, and reauthorizing and updating the Violence Against Women Act to include modern problems like online harassment, Mr. Russo says.

Still, the former vice president frequently evokes the past – particularly when speaking about America’s image abroad.

Mr. Biden’s “No Malarkey!” tour in Iowa coincided with the NATO summit in London where foreign leaders, including Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, French President Emmanuel Macron, and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson were caught on tape appearing to mock President Trump. At first, Mr. Biden said he would wait to comment because of his personal policy of not criticizing presidents while on foreign soil. But by the end of the day, he was referencing the tape directly and his campaign had released an ad saying four more years of President Trump would make it difficult to ever “recover America’s standing.”

Substantively, it makes sense that Mr. Biden would focus both on mending international relationships (he has more foreign policy experience than any of the other Democrats running), and restoring elements of the Obama era (he was there in the White House, after all).

It also makes sense stylistically, says Travis Ridout, co-founder of the Wesleyan Media Project, which tracks political advertising. One of Hillary Clinton’s problems in 2016, he says, was that voters seemed to want change after eight years of the Obama administration. Mrs. Clinton tried to sell herself as a change candidate, but the message didn’t really fit, since she was a longtime establishment figure who had served in the Obama administration. Mr. Biden would likely have similar difficulties if he tried to market himself that way.

“An ‘I’m the change we need’ message is just not going to work coming from Joe Biden,” says Mr. Ridout. “Authenticity is important in politics.”

A transition figure?

Recently, Politico reported that Mr. Biden has been signaling to close allies that, if elected, he would likely serve only one term. The Biden campaign quickly issued a denial, saying Mr. Biden would not make a one-term pledge and that it is not something the former vice president is thinking about.

But Mr. Biden’s age – he would be 82 years old at the end of his first term – may be his biggest liability as a candidate. And in some ways, he has been presenting himself as a kind of transition figure – a trusted, steady hand who can help stabilize the government after the chaos of the Trump years, while the nation figures out what it wants going forward.

That sense of familiarity may help explain why Mr. Biden has continued to hover at the top of national polls and in the top tier in Iowa and New Hampshire surveys, despite lackluster fundraising and smaller crowds than some of his rivals. Indeed, while other candidates have shot to the top of the pack at different times only to fall back again, Mr. Biden has shown steady resilience.

The most recent Iowa poll, from Emerson College, shows Mr. Biden back in the lead in the Hawkeye State, after a spate of November surveys showing Pete Buttigieg, the fresh-faced mayor of South Bend, Indiana, on top.

More than a dozen voters across four town halls say they are torn between Mr. Biden and Mr. Buttigieg. At a Biden event in Iowa Falls, one woman says she is leaning toward Mr. Buttigieg because the country might need a younger president. Another says she is leaning toward Mr. Biden because of his experience, but would like to see Mr. Buttigieg as his vice president.

“I would vote for [Biden] in a minute if he gets the nomination,” says Kurt Kelsey after hearing Mr. Biden speak in Iowa Falls. Still, he and his wife, Arlisse, who farm corn, soybeans, and hay, say they’re leaning toward some of the other Democratic candidates. Mr. Kelsey likes New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and Mayor Pete, and Mrs. Kelsey says she likes Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar.

“[Biden] said some good things, but not really how he’d do it,” says Mr. Kelsey, who’s wearing a “No Malarkey!” sticker on his jacket. “He doesn’t really have a plan.”

“But I agree with him that we can’t have four more years of Trump.”