Florida voters gave ex-felons right to vote. Then lawmakers stepped in.

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga.

Coral Nichols estimates she will have to live to 188 to be able to vote again in her home state of Florida.

For the devoted “duty, honor, country” Republican, that is heartbreak after hope.

Having completed her prison sentence for grand theft, Ms. Nichols believed she would have her right to vote restored after 64 percent of Floridians voted in favor of Amendment 4 last November. The amendment ordered automatic vote restoration for some 1.4 million Floridians who can’t vote because of past felonies.

Why We Wrote This

What does it mean to complete a sentence for a crime? That definition lies at the heart of a change in Florida that means about 500,000 people will not see their voting rights restored.

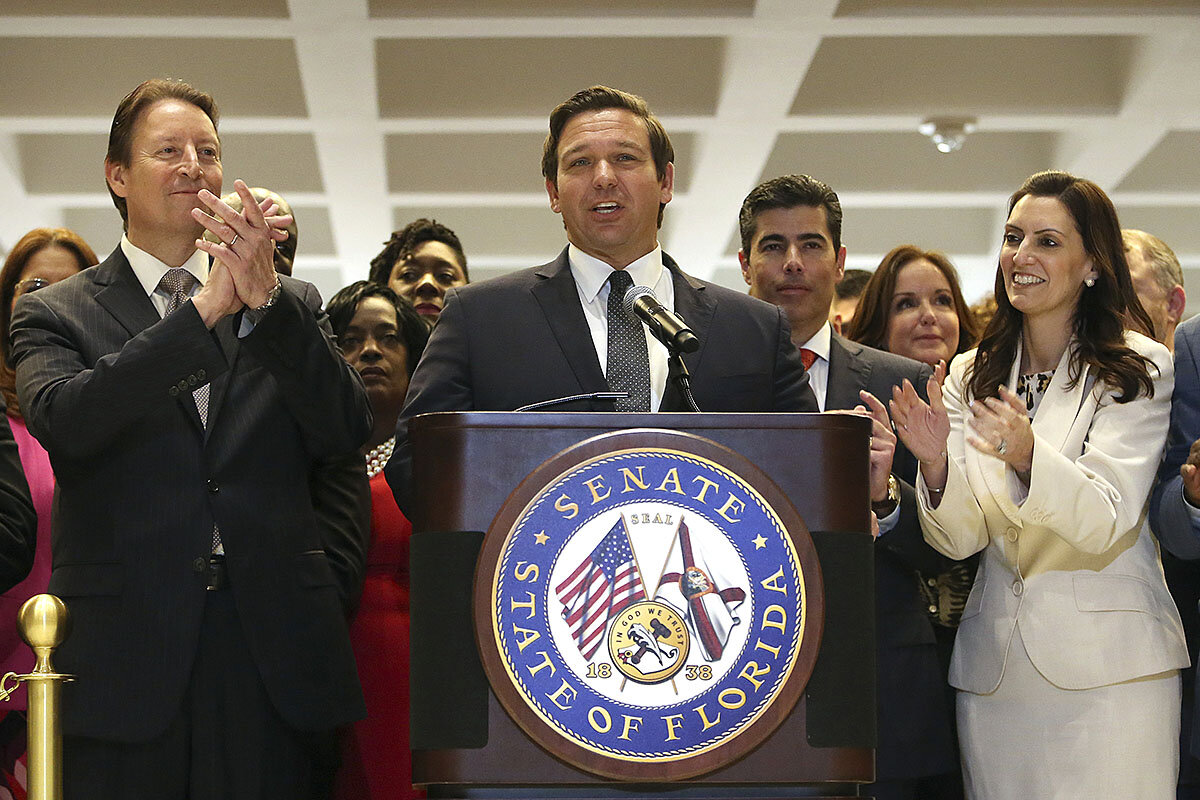

But this week, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis is signing into law a bill that formalizes that amendment but adds a controversial definition: tying the full payment of fees, fines, and restitution to the phrase “sentence served.”

It is not by definition a poll tax, as critics have termed it. But it is also, Ms. Nichols argues, not fair. Yes, she owes $190,000 in restitution, but she says her judge made clear that she has no criminal sentence obligations left after he converted her debt into a civil lien, toward which she pays $100 a month.

“I call it the gray area – people like me who do not fit your black-and-white, cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all policies,” says Ms. Nichols, who runs a nonprofit prison diversion program in Seminole, Florida. “My sentence is complete, I’m completed, and this is the thing that echoes within the very depths of my soul. I am the gray, and lawmakers need to consider the people in the gray.”

The vote last fall became the largest reenfranchisement of U.S. voters since 18-year-olds were given the right to vote in 1971. Originally, it would have involved some 1.4 million Floridians – more voters, in fact, than there are Vermonters.

There will still be as many as 840,000 “returning citizens” surging the polls, a new army of voters that could hold huge sway in the tightly divided swing state.

Yet in withholding the vote from about half a million people like Ms. Nichols, “it’s quite clear the Legislature has gone well beyond what nearly two-thirds of Floridians thought they were voting on,” says University of Florida political scientist Daniel Smith, an expert on how legislatures treat ballot measures.

“The [constitutional] amendment says, if you read it, you have to complete your sentence,” Governor DeSantis said at an environmental issue forum at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “And I think most people understand you can be sentenced to jail, probation, restoration if you harm someone. You can be sentenced with a fine. People that bilk people out of money, sometimes that is an appropriate sentence. That’s what the constitutional provision said. I think the Legislature just implemented that as it’s written.”

Two of the people behind Amendment 4 – Desmond Meade and Neil Volz – opposed the addition. They say their organization, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, attended myriad Senate subcommittee meetings as the bill made its way through the statehouse. One day 600 former felons showed up to discuss the amendment.

‘Win at the margins’

To critics, the decision of the Legislature and governor to impose their will on the law is part of an emerging Republican playbook: winning by subtraction. The stakes are huge, with Florida shaping up to be a key battleground in 2020.

“The plight of voter rights [in Florida] is part of that bigger narrative of the right: to win at the margins,” says Texas Tech University political scientist Seth McKee, a longtime Florida observer. “It’s not a Southern thing. It’s a competition thing.”

Yet the nine-year effort to restore full citizenship to former felons, its proponents say, remains “about people, not politics.”

Amendment 4 “was framed as a question of right and wrong, of morality, of returning a civic voice to people who had served their sentences – a come-back-home,” says David Daley, author of “The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy.” “That united people across racial lines in Florida. ... This was a supermajority of Republicans, Democrats, independents, whites, blacks, Latinos – a real coalition.”

The decision by Mr. DeSantis and the GOP-led Legislature to alter the decision of nearly two-thirds of a state’s electorate is not an uncommon reaction to ballot initiatives. The Massachusetts Legislature voted to delay legalizing recreational marijuana sales after voters approved it in 2016. Also in 2016, voters in Maine approved four ballot questions and a bond issue. In 2017, the state Legislature voted to amend or repeal three of the four measures. (Maine lawmakers tried but ultimately failed to repeal a ranked-choice voting law.)

But Florida also has a history of voter suppression that traces back to the Civil War. Historians there say that the roots can be traced back to the day when a group of boys and older men fended off a Union attempt to take Tallahassee in early 1865, leaving it the only Confederate capital not to fall.

That factored into the Florida’s unique sense of invincibility, that it could in practice, if not legally, ignore what Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles H. DuPont in 1865 called “the exactions of the fanatical theorists.”

“Deep into Florida history, back when Florida was a Southern state, there was a realization after the Civil War that [black people] are potential voters now,” says Gary Mormino, author of “Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams,” a social history of Florida. “And [the disenfranchisement] that happened wasn’t really a conspiracy, because it was pretty wide out in the open. They basically said, ‘What can we do to keep African Americans from taking over Florida?’”

To be sure, Florida was also the first state to abandon the poll tax in the 1930s, setting it on a course that differentiates it from the rest of the Deep South to this day. Today, it is “not a Southern state,” as Mr. Mormino says, but more a smudged window on the nation.

Former felons at the polls

For some former felons who will be able to vote in the next election, the state’s unique social and historical dynamic reverberates in their desire to be “returning citizens.” And the battleground nature of the state, they say, means that the plight of a single person’s rights in Florida should be a concern for all Americans.

“Florida has a national spotlight on it; it’s a transient state, all those different attitudes and traditions coming together – a place where it’s way too hot and people’s tempers get out of control,” says Lance Wissinger, a former felon whose new Florida voter registration card sits behind his ID in his wallet. “It’s the swamp, man. It is a mixing bowl of just craziness, and I think that spills over into the politics of the state.”

In the 20th century, the state pioneered a slew of onerous rules that disproportionately affected black voters. It was the first and only state to add larceny – a civil matter – to the list of disqualifying crimes. The threshold for a third-degree felony was set at $300, the lowest in the United States.

The strategies were so effective that in the 1960s there were only seven black people registered to vote in Gadsden County – a county that had about 12,000 African Americans old enough to vote, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

Before November’s vote, Florida also had the country’s strictest clemency system. Since its rules were changed in 2011 under former Gov. Rick Scott, only 3,005 of 30,000 applicants had their voting rights restored.

That put Florida – ground zero of the 2000 election controversy that was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court – into a class of its own when it comes to disenfranchisement. Some 10 percent of all potential voters and 21 percent of potential black voters had lost the right to vote.

“It is hard to believe that the intensity of the partisan efforts now to put up barriers between certain voters and the ballot box is unrelated to the larger questions of a changing America,” says Mr. Daley.

There appears to be a perception on both sides of the political aisle that more of the new voters may lean Democrat than Republican, but no one actually knows their political makeup, Professor McKee says.

“Republicans own the tough on crime issue, so, knowing that, any Republican would look [at ex-felons] and say, ‘Oh, boy, these people getting out of prison – that is not my constituency.’ And I think they are right, for the most part. But there could be a lot of those white guys who are coming out who like Trump. What is to say they don’t?”

‘A whole brand-new start’

For example, the next time Floridians go to the ballot box, Mr. Wissinger will be there.

After being convicted for manslaughter for the death of his best friend in a drunk driving accident, Mr. Wissinger became a model citizen in prison – the kind of prisoner who, while incarcerated, wins a silver medal at the America’s Chef Competition as part of a work release program and starts a Toastmasters club behind bars.

He is a registered Republican and now owner of a drone company in South Florida, and his quest to vote touches on something common among people who can’t vote: personal quests not just for redemption, but also for restoration of their patriotic worth.

“I don’t think you can be a citizen without a vote,” says Mr. Wissinger. “When I was finally able to register to vote again ... I was asked afterward about how I felt, and I was, like, ‘Man, it’s New Year’s Day. It’s a whole brand-new start to everything.’”

Republicans, says Mr. Volz of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, have not been deaf to those points. The Legislature recently raised the third-degree felony minimum to $750 – a small yet substantial change.

“What we are seeing is that people like myself who have lost our voice and then regained it, we’re the biggest evangelists for democracy,” says Mr. Volz, a former Republican congressional aide who was convicted for his involvement with the Jack Abramoff lobbying scandal. “That means we will continue to move forward in the spirit of Amendment 4, which is one of celebration of democracy and a belief in second chances. Full steam ahead.”