Watch out, 2020: Young voters are on the rise

Loading...

| Boston and Medford, Mass.

Vikiana Petit-Homme tried to get the Boston University student to look her in the eye.

“I can’t vote,” implored Vikiana, the youth leader of March For Our Lives Boston, on the eve of the election. “But maybe you could vote for me?”

The bubbly 17-year-old wasn’t running for office. She wasn’t even advocating a particular candidate. She just wanted to make as many youth voices heard as possible in the most important midterm of her life.

Why We Wrote This

Young people have long been seen as apathetic when it comes to engaging in politics. But this year revealed a remarkable receptivity to their peers’ activism.

The BU student insisted he just didn’t have the time. But despite such resistance, Vikiana and thousands of others like her across the country persisted in urging their peers to vote.

The effort appears to have paid off.

Young people turned out on Election Day in the highest numbers the United States has seen in a midterm in at least 25 years – a double-digit improvement over 2014, according to an early analysis by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE).

They still have a ways to go – their elders vote at far higher rates, and youth turnout was lower in 2014 than other recent midterms, so improving on that was not terribly hard. But the significant uptick this year encouraged many activists, who are already looking ahead to 2020 and planning to build on this year’s success.

The surge in youth turnout stems in part from fear – about school shootings, the state of politics, and the direction of the country. But it also comes from a collective desire to support each other and make positive change at a time when many feel their lives are quite literally on the line.

“This is a sea change [in political engagement]…. They’re the most diverse generation in history so they don’t point their finger at the other,” says Alan Solomont, dean of the Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University in Medford, Mass. “They’re used to growing up as a generation of others.... This generation is about ‘us’ more than about ‘me.’ ”

‘Generation Columbine’

Parents, teachers, and civic leaders have long urged young people to vote, but their approach has often come across as condescending and failed to produce a substantial change in turnout.

This cycle proved different thanks in large part to two events: Donald Trump’s ascent to the White House, and the school shooting in Parkland, Fla. Parkland in particular catalyzed a new generation of get-out-the-vote activists who, as students themselves, proved more effective at persuading their peers that their vote mattered.

Young people are more progressive politically than older generations – particularly when it comes to issues such as race and gender. Many saw President Trump’s election as an affront to their values, and a threat to the country.

“The president is unpopular among young voters – and that’s true among young Democrats and young Republicans,” says George Behrakis, president of the Tufts University College Republicans, though he acknowledges that his Democratic peers may feel greater urgency about putting a check on Mr. Trump’s presidency.

“There’s this environment of fear and worry about the future, and people are beginning to realize that they don’t have a choice but to get involved,” agrees Jaya Khetarpal, vice president of the school’s College Democrats.

First-time voters, dubbed “Generation Columbine,” have never known a world free of school shootings.

And while they’re not monolithic when it comes to gun control, two-thirds favor stricter gun laws, according to a Harvard Kennedy Institute of Politics (IOP) youth poll.

Like the generation that came of age protesting the war in Vietnam, many students see guns as an issue that threatens not only their lives, but the country’s values.

Parkland: It’s not just about guns

The March For Our Lives movement sprung to life after an expelled student killed 17 of his peers and several teachers at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February.

In a closet, with fellow classmates calling their parents in hushed tones, David Hogg took out his phone and began recording in the darkness.

“If we all die, the camera survives, and that’s how we get the message out there, about how we want change to be brought about,” he told Time magazine.

On a living room floor the weekend after the shooting, Mr. Hogg and about two dozen other students began to plan a march on Washington. At least 1.2 million people took to the streets of Washington and other cities and towns across the United States on March 24.

Parkland activists have been on the road since June registering young people to vote in more than 20 states with BBQs, dance parties, speeches, and town halls. They ended their tour back home in their “war room” in Parkland, Fla., calling and texting more than 1,000 friends and other young people until polls closed.

They also sent out automated texts to anyone who had texted “CHANGE” to 977-79.

“Y’all!! 2 days until Election Day!!” read one.

“Hey – yes, there have been lots of messages. Just ... don’t give up now!” read another.

The midterm election was the first major test of whether that movement would translate from marches to ballots, and early analysis suggests that while they didn’t ace the test, they certainly passed.

The results show a country still divided over gun control. A statewide recount is under way, but it appears that activists did not secure Democratic, anti-NRA seats in their home state of Florida.

But the Parkland movement goes beyond any one issue, says Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of CIRCLE at Tufts. “It normalized political engagement and young people leading the way.”

A post-election video selfie message from Parkland students Hogg andEmma Gonzalez thanks voters for “helping to save our generation.”

While the national spotlight has shined most brightly on the Parkland activists, they were building off of and working with often-ignored movements led largely by people of color.

As a Haitian-American, Vikiana sees the movement as a platform to highlight the more prevalent issue of everyday gun violence. While her civic engagement predates March For Our Lives, she admires its power to activate many of her peers – some for the first time.

“Young people are so used to being looked over… that when you have someone finally tell you that you are smart, you are powerful, and you can make change, it stirs up something in you,” she says.

Record youth tilt toward Democratic candidates

The midterms laid bare a growing ideological divide between younger and older generations that will play out in 2020 and beyond. That divide barely existed in the early 2000s. Young people voted for Democratic House candidates by a more than 2 to 1 margin, the widest divide ever for voters under 30.

This year’s 4 million increase in turnout came almost entirely from those voting for Democrats, which most likely played a key role in flipping the House, according to the IOP.

If youth turnout on Tuesday had been at usual midterm rates, districts such as Texas’s 32nd and Georgia’s 6th would not have been turned by Democrats. Young voters also helped Democrats win a Nevada Senate seat and made the Texas Senate race, with Democratic darling Beto O’Rourke, a tight race rather than the typical blowout.

Those results are likely due in part to Democratic campaigns and get-out-the-vote groups increasing their social media spending while outside liberal groups zeroed in on the youth vote. NextGen America, for example, spent $33 million.

Social media platforms, companies, and celebrities stepped up get-out-the-vote efforts as well.

On Election Day, Instagram collected every post from a user’s friends into a user-unique “We Voted” story. And on the dating app Tinder, a pop-up message greeted users with “Tinder can wait. Go vote.”

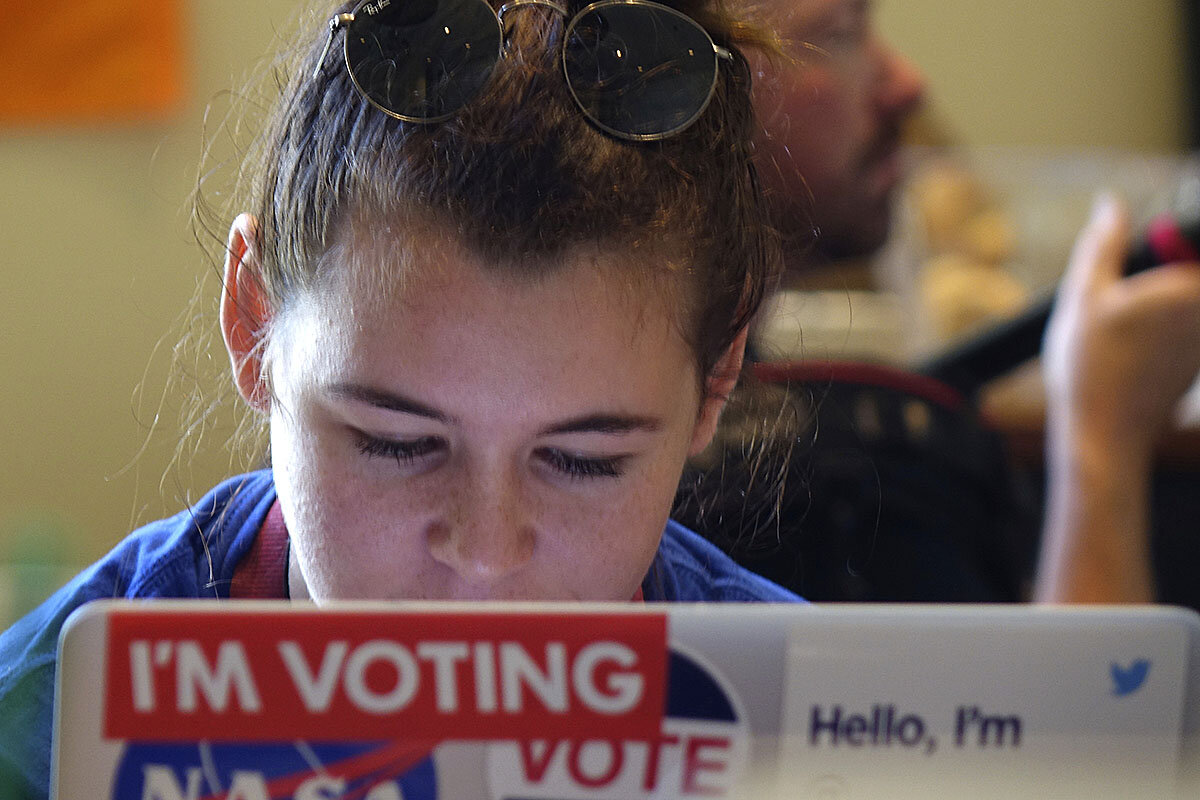

"Honestly, social media has been blasting it for so long, I feel like I need to vote,” said Julie Lin, an 18-year-old first time voter at Tufts on her way to a polling station in Somerville, Mass.

Next step: Holding lawmakers accountable

Now the question is: Where does it go from here? As this generation of fervent young activists matures into adults, will the movement grow more powerful? Or will it dissipate?

This year’s election is most likely just the beginning, says Peter de Guzman, student outreach coordinator for JumboVote, Tufts’ campus-wide voting initiative. After all, many of those students inspired by March For Our Lives, like Vikiana, are still too young to vote.

“My 16-year-old sister called me crying when Parkland happened,” says Mr. de Guzman. “It was a big moment in [high schoolers’] lives and we will see the impact even more in two years.”

While young activists are looking to boost turnout further next time around, they are also looking beyond the ballot box.

“Voting is the new hip thing that young people are doing – which is great because we do need young people to vote,” says Vikiana. “But a lot of people forget that there’s accountability afterward.”