Gatekeepers of the Trump revolution

Loading...

| Washington

It was a somber scene in the GOP-controlled Senate. Republicans were set to blow up a historic Senate rule so they could bust through a Democratic blockade and confirm Neil Gorsuch for the US Supreme Court with just a majority vote.

Rather than the usual milling around at vote time, when senators from both parties mix it up with slaps on the back and chitchat, many members began the series of votes on this April morning sitting quietly at their desks. Republicans on one side, Democrats on the other.

Which is why Sen. Susan Collins stood out. Carrying a bright green folder, the Republican from Maine crisscrossed the chamber floor, quietly approaching her colleagues – placing her hand on a shoulder, bending down to whisper, then opening her folder.

Even as the Senate was “nuking” the 60-vote threshold for Supreme Court nominations – a high bar meant to forge consensus and protect minority-party rights – Senator Collins was gathering signatures for a bipartisan letter to the Senate leadership. The petition sought to preserve the chamber’s last supermajority threshold – not for court appointments but for passing legislation itself.

This was classic Collins, ranked in 2015 as the most bipartisan of the Senate. Such moderation actually makes her a particularly powerful senator. In this increasingly polarized era, Collins is a crucial swing vote in a chamber where Republicans hold only a tenuous 52-to-48 majority, putting her in a position to help shape or stall the legislative agenda of President Trump.

When it comes down to it, experts say, the Trump revolution will largely succeed or fail in the Senate, depending on lawmakers like Collins and various constellations of members that shift with the issues. Trying to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, as well as dealing with issues such as tax reform, infrastructure spending, and the federal budget, will require a careful corralling of senators – even as powerful forces, such as elections, tug at lawmakers’ political ids.

“The crux of the Trump agenda begins and ends with that body,” says Jim Manley, former spokesman for retired Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid of Nevada.

Of course, there are caveats to the Senate being the arbiter of the Trump presidency. One is the White House itself: Can this politically inexperienced administration unify its message and learn to engage more successfully with Congress? And what about the mercurial and fractious Republicans in the House?

Still, it is generally the Senate – with its traditions and rules that enhance the individual power of each of its 100 members – that will shape much of what happens in the next four years, rather than the much larger House, where the majority rules. The tight divide in the Senate complicates matters. When Senate rules require a simple majority vote, Republicans can afford at most two defections. When the rules require a 60-vote threshold, as they still do for spending bills and most major legislation, Republicans – if they hang together – will need eight Democrats.

How much ultimately gets done will hinge in large part on the Senate’s two Kasparov-like chess masters – majority leader Mitch McConnell (R) of Kentucky and minority leader Charles Schumer (D) of New York. But behind them are a number of coalition builders and busters who will play crucial roles, including these six, who range from a rookie Californian to an octogenarian songwriter.

Susan Collins: Courting a moderate

Collins is a fifth-generation public servant who draws inspiration from Maine’s first female US senator, Margaret Chase Smith, and from her political lineage. Both her parents served as mayor of her hometown of Caribou, on the northeastern tip of Maine, where her family runs a lumber business that dates back to 1844.

The state has a tradition of sending independent-minded senators to Washington, and the moderate Republican carries on that tradition. It’s what makes her one of the most wooed members of the chamber.

“Not a day goes by that I do not hear from a colleague in the Senate, asking me to either join in an initiative, or what I will do on a particular issue,” she says in an interview. “That’s very nice in some ways, but it puts a lot of pressure on me,” especially now that the president is a member of her own party, she explains.

Still, that hasn’t changed her approach to her work: searching for compromise when she can, checking the president when she feels she must.

Though she did not vote for Mr. Trump in November, she stood with him on the Gorsuch nomination after having tried – and failed – to broker a bipartisan truce to avoid the explosive rules change. But she did not support Trump’s choice for Education secretary, Betsy DeVos.

Collins has deep reservations about the GOP plan to overhaul Obamacare that narrowly passed the House May 4, saying it would hurt Mainers, particularly senior citizens. She and several other Republican senators have made it clear the bill will never survive the Senate intact. Their message helped stall it in the GOP-controlled House in March.

Before the House even unveiled its plan, she and a Republican colleague, Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a physician, wrote their own compromise bill: States that like Obamacare could keep it; those that don’t could use Affordable Care Act funds to develop a plan that covers more people. They've picked up four Republican co-sponsors and are reaching out to Democrats.

Collins says the president called her about the bill. He found it intriguing and sent White House economic adviser Gary Cohn and an assistant to talk to her and Senator Cassidy about the specifics.

In the end, though, the administration backed the House version. It aimed to pass it through a special budget maneuver that requires only a majority vote in each chamber.

As a steadfast defender of the Senate’s deliberative traditions – Collins herself has never missed a vote in her 20-year tenure – she is skeptical of circumventing the normal legislative path for such big and complex issues as health care and tax reform. She prefers the committee process, hearings, and amendments in which the House and Senate have a chance to work their will and come to some kind of bipartisan solution.

“I don’t think this is a good way to proceed, and I would think we would have learned from [Obamacare] when President Obama jammed the bill through the Senate,” she says.

The GOP leadership in the Senate has meanwhile set up a working group of 13 Republicans to fashion the Senate's own Republican health-care bill. Neither Cassidy nor Collins is on it – and notably, no women either. At least one former Washington insider suggests that Senate leaders should consult closely with the even-tempered Collins, not just because she is a crucial swing vote, but because she also serves on some powerful committees, including appropriations.

“I used to work very closely with Susan every day. And the same thing with Olympia Snowe,” says former Senate majority leader Trent Lott (R) of Mississippi, referring to Collins’s former colleague from Maine. “If you get them in on the takeoff, they’ll probably be there on the landing.”

Yet there is some question whether Collins will even be in the Senate in a few years. She is weighing a 2018 bid for governor. The deciding factor, she has said, is where she can “do the most good” for Maine.

Joe Manchin: Squeeze play

When Trump gave his first address to a joint session of Congress in February, most Democrats sat stone-faced or clapped politely in their laps. Not Sen. Joe Manchin (D) of West Virginia – an ultra-red state that Trump won by more than 40 percentage points. Like a jack-in-the-box, the West Virginian kept popping up to applaud.

Political analysts point to Senator Manchin and nine other red-state Democrats up for reelection in 2018 as a possible source of votes for Trump’s priorities. These are relative moderates who – like Collins – could turn out to be key swing votes.

“The Senate in some respects belongs to Joe Manchin and Susan Collins,” says John Pitney, a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, Calif.

Manchin hates it when reporters bring up his looming race as a possible factor in his votes and friendly relations with the president. It doesn’t weigh “one iota” in his decisions, he tells a scrum of reporters. He’s simply representing his state. And as a former governor, he’s showing deference to Trump as a fellow executive.

While many of Manchin’s colleagues have put up a wall of resistance to the president, the West Virginian was one of three Democrats who voted to confirm Mr. Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. He has also voted to approve several of Trump’s most controversial cabinet nominees, such as former Sen. Jeff Sessions as attorney general, Steven Mnuchin as Treasury secretary, and Scott Pruitt to head the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). He has the most conservative voting record of Senate Democrats.

Manchin disagrees with Trump on health care, but he comes from a coal state and has railed against EPA over-regulation. (He keeps a bronze statue of a coal miner in his office.) The crosscurrents he is facing are similar to those confronting Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D) of North Dakota – also an energy state and one that Trump won by more than 35 points.

Both Manchin and Senator Heitkamp trekked to Trump Tower for a visit with then-President-elect Trump and were invited to the White House with a small group of moderate Democratic senators early in his administration. Manchin feels he can call the president at any time, as he did recently to get his support for health care for miners.

In six weeks, “I spoke ... with this White House and this president more than I did with the other president in six years,” he says, referring to Barack Obama.

When minority leader Schumer announced his new leadership team last year, Manchin was designated as the Democrats’ outreach guy to Republicans.

But the West Virginian says there hasn’t been much to reach out about yet. The GOP has been focused on nominations or other issues – such as health care and regulation rollbacks – that have only required a majority vote. Presumably, that will change now that Congress is moving into budgeting and other legislating that will require bipartisan support to clear the Senate.

“If this place is going to work, you’re going to have to look at 10 or 12 Democrats,” says Manchin, striding from the Capitol to his office on a gloriously warm spring day. He is a tall man, with a thick shock of salt-and-pepper hair, who lives on a houseboat when he’s in Washington.

Republicans will have to bring in moderates, he continues, and “get off this hard-line thinking that everybody else has got to bow to them because they’re the majority.”

The question is whether Democratic moderates will play. At the start of the year, Republicans seemed confident they would get enough Democrats to back Gorsuch to clear a 60-vote threshold. In the end, only three Democrats, all red-staters, voted to confirm him.

“They can’t count on red-state Democrats coming to them just out of fear of defeat,” says Ross Baker, an expert on the Senate at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J.

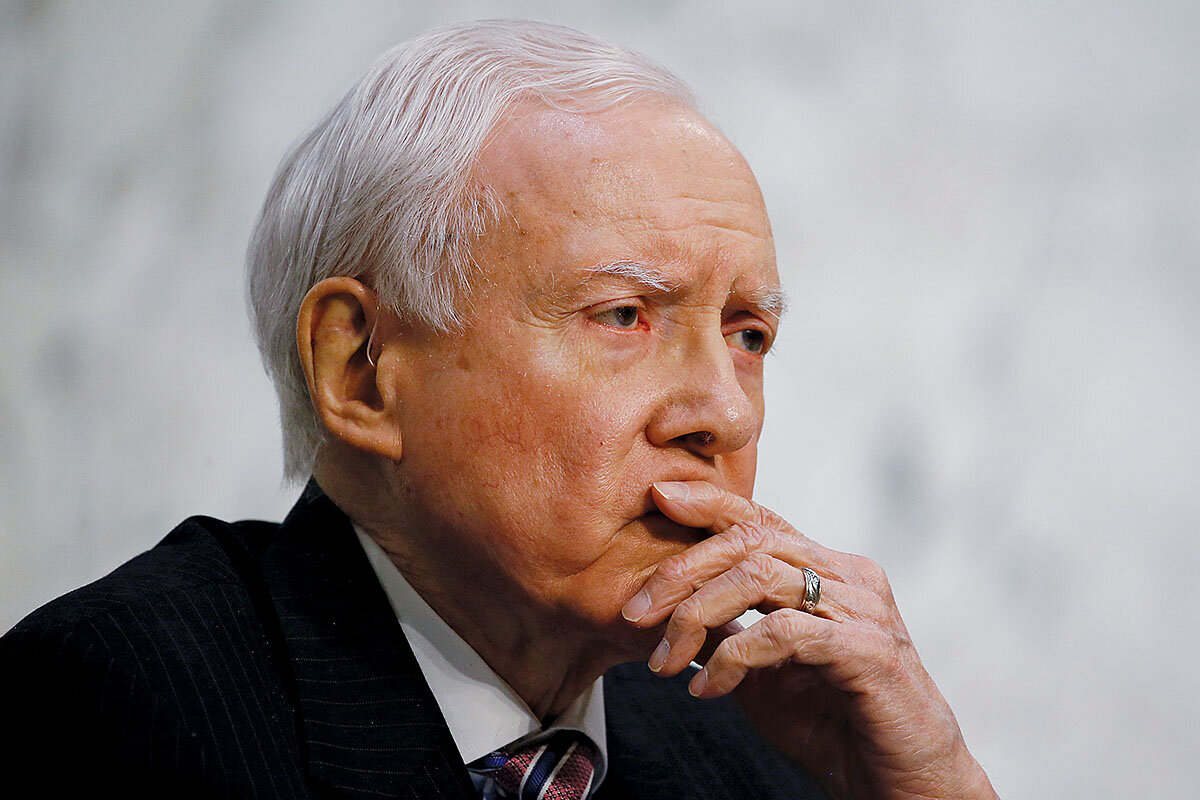

Orrin Hatch: Writing a Trump ballad?

One of Trump’s indispensable allies on the Hill is Orrin Hatch of Utah, the longest-serving Republican in the Senate. The octogenarian, who admiringly calls the president “a shrewd cookie,” chairs the Senate Finance Committee. Almost everything Trump cares about runs through that panel: tax reform, infrastructure, trade, and revisions to health care.

“Any way you slice it, Orrin Hatch will be a key player,” says former GOP majority leader Mr. Lott.

On taxes, Senator Hatch is conferring regularly with the top GOP tax writer in the House and with the Trump administration. This is a hugely complex issue, he tells reporters, “even more complex than health care.” It will test his 40-plus years as a legislator – and his ability to create harmony out of discord.

Republicans are divided over tax reform. While they generally agree on the president’s broad goals of a simpler code, lower business taxes, and a middle-class tax cut, they disagree over details – especially how to pay for it all. Hatch and other Republicans, for instance, doubt the president’s proposed low corporate tax rate of 15 percent will make it through Congress.

This internal division does not bode well for the party’s strategy on pushing through an overhaul. As with repealing Obamacare, the GOP plan is to use a special budgetary procedure to pass a tax bill with only a majority vote.

Republicans found out how tough that was with their health-care bill. So might they try a more bipartisan strategy? That was the road to the last big tax overhaul in 1986.

Despite his deep conservatism, Hatch is also known for his bipartisan work – and friendship – with the liberal lion from Massachusetts, the late Sen. Ted Kennedy. Hatch even wrote a love song, “Souls Along the Way,” for Senator Kennedy and his wife, Vicki, that was featured in the film “Ocean’s Twelve.”

The senator is an established songwriter, including one he scratched out during a committee hearing, with gold and platinum albums to his name.

Some wonder whether this could be a Kennedyesque moment for Hatch – a time to come together with the lead Democrat on his committee, Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon. The two have worked well together in the past, for instance, on trade.

“Oh yeah,” Hatch said in a recent interview. “I intend to work with him, and I intend to work with House Democrats as well,” he said, rumbling toward his office on one of the Capitol subway trains. However, he lamented, “I wish we had more Democrats in the House and Senate who [were] more willing to work with us.”

Senator Wyden’s affection for Hatch is mutual. “We’re former basketball players,” says the 6-foot-4 Wyden about his 6-foot-2 colleague. “We like telling stories. He sort of treats me like I’m his kid, and I’m very fond of him.”

However – and this is the key complaint of Wyden – for something as serious and difficult as tax reform, Democrats need to be consulted from the “get-go.” When Republicans go off on their own, write the bill they want, and then try to round up some Democrats if they need them, that’s not bipartisanship, he says.

Yet Democrats are playing tough, too. They demanded that Trump release his tax returns as part of any tax overhaul. When the White House outlined Trump's tax reform plan April 26, Wyden denounced it as offering “crumbs” to working people and “cakes to the fortunate few.”

Hatch reminisces that it was Kennedy who, early on, came to him. The committees at that time were almost all chaired by Southern Democrats who did not have a very high opinion of the senator from Massachusetts – though they did like Hatch.

“Kennedy was wise enough to realize that, ‘hey, I might be able to get something done with Orrin,’ and as you know, we passed all kinds of important legislation.”

But as Hatch so often comments these days, the Senate isn’t what it used to be. He sounds like Manchin, but with the GOP perspective: “The question is whether we can get the Democrats to work with us – to get off the kick that Hillary should have won.”

John McCain and Lindsey Graham: birds of a feather

It was a tender scene: Sen. John McCain wiping his eyes as his close friend Sen. Lindsey Graham sang his praises at a CNN town hall in March. “I love him to death,” said Senator Graham, who then dabbed his own eyes.

They were acting like a couple of lovebirds in that moment, but usually these two are fierce defense hawks, with Senator McCain of Arizona chairing the Armed Services Committee and Graham of South Carolina, also on the committee, as his wingman.

During the presidential campaign and into Trump’s presidency, the two senators regularly clashed with the commander in chief – criticizing him about Russia and his “America first” policy that seemed to vacate the country’s leadership in the world.

The two were shaping up to be formidable opponents of the president’s stances on foreign affairs. That is, until Trump in April ordered a barrage of Tomahawk cruise missiles to rain down on a Syrian airbase in response to a chemical weapons attack. Both men immediately released a supportive joint statement: “Unlike the previous administration, President Trump confronted a pivotal moment in Syria and took action.”

The plaudits from both men have been flowing since then. April turned into a month of muscle flexing, with the US dropping the “mother of all bombs” on Islamic State fighters in Afghanistan and taking a tough stance on North Korea.

“I am like the happiest dude in America right now,” Graham told “Fox & Friends” on April 19. “We have got a president and a national security team that I’ve been dreaming of for eight years.”

The senator said North Korea and China should start thinking anew about Trump. “I am all in. Keep it up, Donald,” he said.

All in? Perhaps for now, but it is not clear whether the president will go far enough over the course of his presidency to satisfy this duo – or other hawks in Congress.

Trump wants an increase of $54 billion in defense spending for 2018. McCain and his House counterpart want far more and vow to defend State Department funding. Last week, McCain took to the opinion pages of the New York Times to lambaste Secretary of State Rex Tillerson for giving short shrift to defending human rights around the globe.

Militarily, the president authorized one strike on one airfield in Syria. But McCain and Graham want the Syrian Air Force completely grounded, more support for vetted opposition fighters, and a no-fly zone over Syria.

“The only thing they understand is force,” McCain told reporters, speaking of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Kamala Harris: Great expectations

Only four months in the Senate and Kamala Harris is already telling Californians she’s got “bloody knuckles” from fighting Trump.

It’s rhetorical flourish, true, but there’s no question that the Golden State’s freshman senator has started off fiercely opposing the president. When Senate Democrats say they’re the “emergency brake” on the Trump administration, that includes members such as Senator Harris – considered a rising star in the party, and sometimes mentioned as a possible 2020 presidential or vice presidential candidate.

“Within days of being sworn in, she was smart enough to disregard the old rules about freshman senators [being] seen and not heard,” says Mr. Manley, the former spokesman for Mr. Reid.

There she was, a featured speaker at the Women’s March on Washington, then joining protesters against the president’s travel ban, and aggressively questioning his cabinet choices at hearings. She jumped to the defense of Sen. Elizabeth Warren after majority leader McConnell shut down the floor speech of the Massachusetts Democrat for impugning a colleague – Republican Senator Sessions, who went on to become attorney general.

“We need to watch this Jeff Sessions,” said Harris at a recent town hall in Los Angeles. Questioning Mr. Sessions's objectivity, Harris said last week he should resign over the firing of FBI Director James Comey.

The question is what the Democrats, as the minority party, can do other than just watch. They couldn’t block the president’s Supreme Court nominee nor his cabinet picks, though they did manage to build enough momentum against fast-food executive Andy Puzder that he withdrew from consideration as Labor secretary.

Democrats, however, are not without power, especially in the Senate, where they can still threaten to block legislation and use rules to delay things. Now that Congress is addressing spending issues – its main job – Democrats can throw up a 60-vote barrier.

So when Harris promised folks – to rapturous cheers – at her town hall that she would do all she could to block a budget if it included money for the president’s border wall, that wasn’t an idle threat. The wall didn’t make it into this year’s budget.

Still, it would be a mistake to think of her as a flat-out “resister” to all things Trump. Harris says she is defending the interests of her state – one that voted overwhelmingly for Hillary Clinton, has more unauthorized immigrants than any other state, leads the country in the number of people covered by Obamacare, and is at the forefront of the fight against climate change.

At the same time, the senator is willing to work with the Trump administration on such issues as infrastructure and disaster relief – perennial needs in her state. And she has urged progressive activists to rally behind, rather than protest, vulnerable conservative Democrats such as Manchin and Heitkamp.

“She is more practical than her reputation suggests,” says Professor Pitney. As for her “stardom,” Pitney describes her as “new and fresh” compared with the senior set of Democratic power brokers in Washington.

Harris is the first Indian-American and second African-American woman to serve in the Senate (her parents came from India and Jamaica). Growing up in Berkeley, Calif., she attended civil rights marches with her parents. Though her progressive roots run deep, some liberals think she was too cautious on criminal justice and other reforms while she was California’s attorney general.