Why Trump rollback of Obama climate policies could be a long slog

Loading...

| Washington

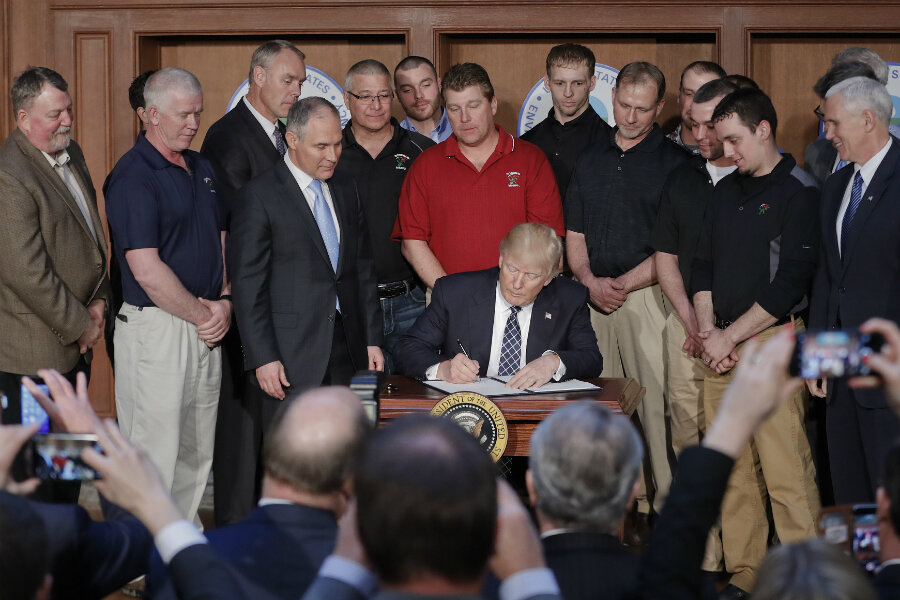

With a flourish of his pen Tuesday, President Trump promised a full-scale assault on the Obama administration’s signature climate-change initiative.

But changing America’s course on the issue isn’t likely to be that simple.

Mr. Trump's executive order starts the process of scrapping Mr. Obama’s Clean Power Plan, which calls on states to reduce electric-utility emissions that scientists say are changing Earth’s climate. Instead, Trump wants to go all-in on expanding US energy jobs, notably in coal mining and fossil fuels.

“You’re going back to work,” he told a group of miners who flanked him as he signed the executive order in Washington.

Yet when it comes to climate change, a key question remains: Just how will the administration go about undoing policies with deep legal and scientific roots?

The US Supreme Court has affirmed the view that carbon dioxide and other gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are pollutants, and the Environmental Protection Agency has made a formal “endangerment finding” that these pollutants threaten public health and face federal regulation under the Clean Air Act.

Another hurdle for the rollback effort is public opinion. Most Americans and even many Republicans support action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The result is that, while Trump and his team can certainly slow US efforts to respond to climate change, it may be much harder for them to lock a different direction into place. For instance, unless that “endangerment finding” is overturned – which policy experts say would be extremely difficult – Trump could find himself needing a “replace” strategy in the form of his own climate policy, rather than merely a “repeal” of Obama’s.

“The executive order has some symbolic importance for some of President Trump’s supporters, but on the ground it’s not clear how much difference it’s going to make,” says Richard Revesz, an environmental law expert at the Institute for Policy Integrity at New York University School of Law.

The Paris factor

Trump’s stated focus is on unlocking job opportunities. He didn’t mention climate change in calling for the Obama policy, “this crushing attack on American industry,” to be expunged.

But a senior administration official said Monday that he did not know how long the effort could take: “whether that's two years, three years, or one year, I don't know." And in the longer term, it could involve steep legal battles – if Trump tries to argue that America needs no federal policy on climate change – or pressure to come up with a new policy approach.

Many influential conservatives hope to see a Trump assault on the consensus view, evidenced globally in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, that carbon emissions need to be reduced.

“My guess is that eventually Trump will see that he has to formally renounce Paris, or some judge will try to force him to implement the CPP [Clean Power Plan] and all the rest,” says Benjamin Zycher, an environmental policy expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

“I don't think any [new policy] should replace them, as there is no evidence whatever of a climate ‘crisis,’ and the effects of such policies would be unmeasurable,” Mr. Zycher adds, commenting by email.

Many policy experts, however, say backing out of all action on climate change isn’t realistic.

“Given that the virtual unanimity of scientific evidence points to the endangerment finding [being valid] it’s hard to imagine a court would uphold” an effort to overturn it, Mr. Revesz says.

A window of opportunity for conservatives

And for some conservatives who support action on climate change, this offers a potential window of opportunity – albeit some ways down the road.

“I believe there will soon enough be a significant backlash” to a repeal-only climate strategy by Trump, Ted Halstead, leader of the recently formed Climate Leadership Council, said at a Washington event Monday. “The majority of Americans care about this issue.”

His group is pitching a conservative-oriented approach to climate action, backed by former Reagan and Bush cabinet officials, that would tax greenhouse emissions and pay out the proceeds as “carbon dividends” to all Americans.

Mr. Halstead said he’s under no illusions his idea will be quickly embraced on a bipartisan basis. But he argues it’s realistically positioned for whenever Trump or others are ready to seek an efficient way to reduce emissions.

The Paris Agreement, under which nations are setting their own targets for emission reductions, is built around the goal of holding a global rise in temperatures to no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Reaching that goal, scientists say, could avert the worst impacts of climate change.

Allowing innovative responses

Many policy experts see some form of government-set “price” on carbon emissions as the optimal way to reduce emissions, because it then leaves businesses and consumers free to respond in innovative ways.

“I know we’re going to win,” says Bob Inglis, a Republican former congressman who backs a carbon-price approach. “The question is whether we’re going to win soon enough to avoid the most serious consequences of climate change.”

For now, Trump has shown little interest in climate change except to publicly dismiss it. Still, significant debate is under way within his administration about policies, such as whether the US should remain in the Paris Agreement or try to back out.

Trump’s executive actions Tuesday included various steps that he said will boost energy production and jobs, including easing regulations on oil and shale gas producers and making it easier to mine coal on federal lands. He also aims to undercut Obama’s emphasis on factoring the “social cost of carbon” – the impacts of climate change – into federal decision-making.

Since states have their own policies (often boosting renewable energy sources like wind and solar), and since other market forces play a key role in job creation, it’s not clear if Trump’s policies will have dramatic impacts on US energy markets or jobs.

And on climate, all this, along with the goal of dismantling the Clean Power Plan, could mean several years ahead with little in the way of federally induced cuts in US emissions.

“My guess is with the CPP for instance, there will be some scaled-back replacement,” says Joseph Majkut, director of climate science at the libertarian Niskanen Center in Washington.

“Whether Congress or this administration will embark on a more ambitious program, like putting a price on carbon in lieu of regulation, I think they certainly have an opportunity. There would be plenty of support for them if they do that, but I see no indication that they will do that at this time.”