What an Ohio town reveals about the decline of hope in US politics

Loading...

| Springfield, Ohio

This is a town of overgrown lots, of boarded-up homes, of vacant businesses. It is a town where the remaining sections of the mammoth Crowell-Collier publishing plant loom, a brick-and-concrete monument to a thriving city that once was but increasingly is no more.

It is a town of Dick Hatfields.

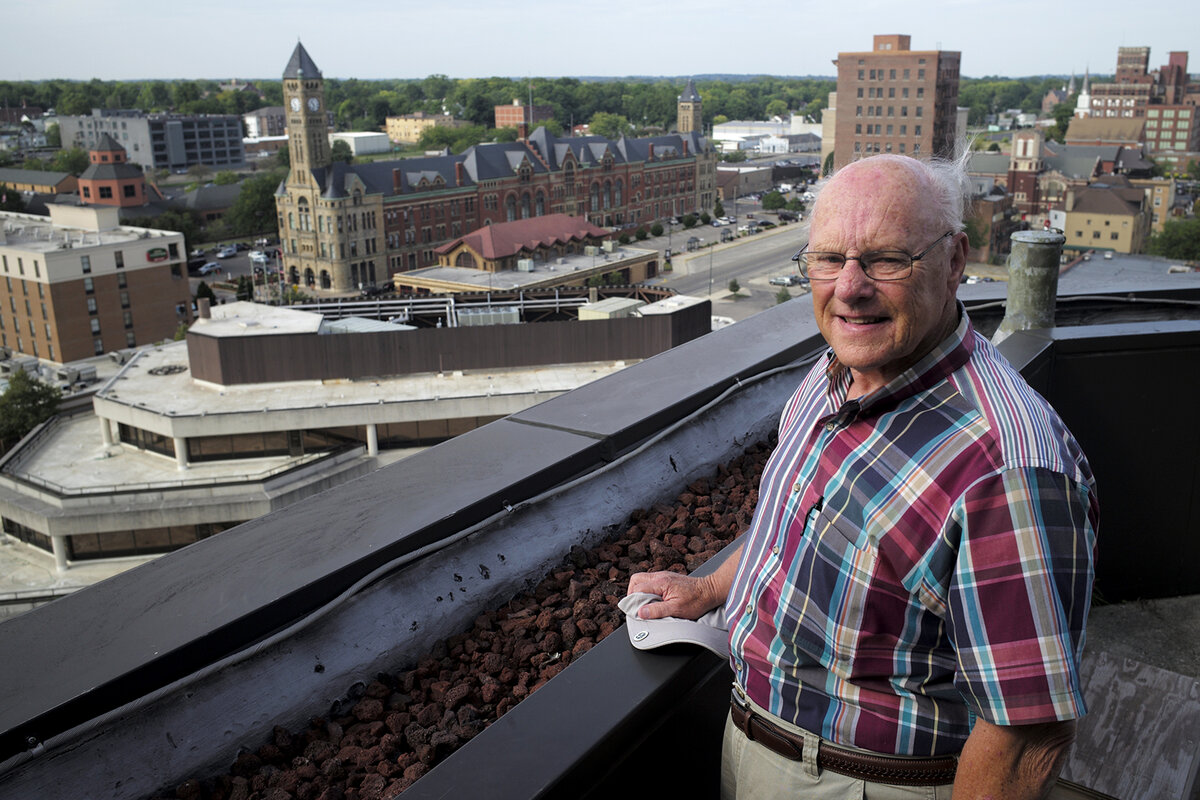

He once prowled the streets of Springfield in a ’53 Chevrolet. He can point to where the old root beer stand used to be. He remembers when Duke Ellington and Count Basie came to town.

When he recently built a replica of his ’53 Chevy – down to the flames on one side – Mr. Hatfield says he “still went downtown to ‘beat the block,’ but it was like there was nobody here to see.”

Yet this is also a town of well-appointed Victorian buildings lining once-genteel thoroughfares. It is a town where the Crowell plant might – just might – be an anchor for a new vision of Springfield.

It is a town of Kevin Roses, bounding 30-somethings who acknowledge that Springfield might not be the “Champion City” it once was. But in that history are the seeds of a renaissance, if only the city would grab it.

Since the shuttering of Crowell – on Christmas Eve 1956, as locals tell it – Springfield’s story has been one of decline, sometimes in an almost imperceptible annual drip, or sometimes, with the closure of another of the city’s factories, in a great rush.

Now it stands as capital of an unenviable American trend: the decline of the middle class. Between 2000 and 2014, Springfield saw more of its middle class slip down the economic ladder than any other metro area in the United States, tying Goldsboro, N.C.

As voters across the country have voiced their disdain for Congress and all things Washington, it is perhaps not surprising that many in Springfield say they don’t necessarily see politics or even their preferred presidential candidate, either Democrat Hillary Clinton or Republican Donald Trump, as being a central part of their or the city’s future.

Yet in an election whose unusual twists have been driven by a white working class that feels like it is losing ground, Springfield’s story resonates.

The two competing worldviews – the Hatfields and the Roses – have played out in similar communities across the country, says Chad Broughton, a University of Chicago professor who spent 12 years in Galesburg, Ill., to study the community after its primary employer, Maytag, moved its manufacturing jobs to Mexico.

Springfield is a portrait of a city struggling for hope.

Nationwide, there are new shoots of optimism for the middle class: Census figures released Tuesday showed a 5.2 percent increase in income for the typical American household in 2015 – the first real increase since 2007. But middle class income growth has been largely stagnant for decades.

The Trump phenomenon is only one manifestation of how the pressures on a largely white middle class have refracted politics. Much deeper is the perception that, for many, the future has already closed in front of them – and Washington has seemed unable or unwilling to stop it.

“The American dream is breaking apart because there’s not really a standard pathway anymore, and that does bring about a lot of insecurity for the majority of Americans that don’t have a degree beyond high school,” Mr. Broughton says. “There’s anxiety and the feeling of really powerlessness to do anything about it. So what happens to them?”

• • •

On a recent day in July, about 40 people have gathered around Mr. Hatfield on the parched asphalt of downtown Springfield. This is one of his so-called “nostalgia” tours.

The tours run $12 each and include a free drink afterward. The promise is modest: Remember old times and hear some lesser-known facts about Springfield’s history. The tours are generally sold out.

The tone is upbeat and Hatfield, a former radio deejay, treats it as something of a comedy routine. Now, he notes, there’s nowhere to work in radio because the city no longer has its own station. Tune to the old frequency and “you’ll hear somebody saying the rosary in Portuguese,” he says to a laughing crowd.

His routine is well-practiced. Did you know Springfield once had a pianomaker who sold pink keys to Liberace? Did you know that the root beer stand that used to be here was the first in the United States?

Then he points to an empty lot and tells the crowd to make its way there for the next part of the tour.

“There’s no buildings to go to, we’ve just got to go to empty places,” he adds.

When the Pew Research Center set out to determine which American cities lost the most economic status, Springfield came in first (or last) with Goldsboro. It lost more high-income earners and gained more low-income earners than any other metropolitan area between 2000 and 2014; the difference was 16 percentage points.

In Springfield, the echoes of a more prosperous past are everywhere.

At the minor league baseball stadium, the few in the stands hum along to a 1950s television advertisement that evokes Springfield’s ever-present nostalgia, a sing-songy refrain of, “We love baseball, hot dogs, apple pie, and Chevrolet.”

Around town, T-shirts, buses, and stoplight buttons herald “The Champion City,” harking back to the turn of the 20th century, when Springfield was one of the great worldwide hubs of agricultural machine-making, churning out International Harvester’s Champion machines.

Springfield even has a Frank Lloyd Wright – the Westcott House.

But the decline that began with the shuttering of the Crowell plant gained speed when International Harvester (now Navistar) made a big round of cuts in the 1990s.

That was when the Springfield of today really began to take shape, says Rob Baker, a political scientist at Springfield’s Wittenberg University.

“When they pulled out again and really decimated that big plant out there, that really began to create that divide,” Baker said. “A lot of people left town. But the folks who stayed, the older generation … they got pretty down about everything. And some other folks have come in, younger folks, who are more optimistic.”

The divide is sharp.

Take Raymond Upshaw, a Springfield resident in his late 60s and an African-American who voted for President Obama in 2008. He now supports Mr. Trump.

“They may have elected a black man to the White House, but they didn’t follow him,” says Mr. Upshaw, whose construction business has not done well for years. He plans to vote for Trump because he believes the US can’t rebuild until after it hits rock bottom. “I don’t expect Trump to do a good job. I’m putting him in there so he can continue to destroy this country.”

Upshaw isn’t necessarily emblematic of the mood in town, but of an underlying sense of mingled frustration and fear. So many things that once felt so certain, now aren’t.

• • •

Ann Armstrong is among those taking the nostalgia tour. The Republican, who voted for Governor Kasich in the Ohio primary, is congenial and upbeat, and, like many here, doesn’t really want to go into politics at length. But after some prodding, she admits that she has grave concerns.

While out at a ceremony for a new museum wing at Wright-Patterson Air Force base, a key area employer, Ms. Armstrong says her mind drifted toward possible terrorism.

“All I could think about was, ‘Gee, I wonder if the security has tightened up, because the Air Force museum would be a good place to blow up,’ ” she says.

She adds, laughing, “They wouldn’t let me carry my gun.”

Armstrong wishes Kasich were still in the race. Kasich, who won the Ohio primary, took Springfield and surrounding Clark County over Trump by three percentage points. Indeed, Springfield hardly comes across as revolutionary, sitting in the district of former House Speaker John Boehner, Mr. Establishment. But many voters in the city, which tends to vote Democratic, likely crossed over and voted for Trump, political experts say.

Armstrong says her mistrust of Clinton extends to Obama. Many of her Republican friends believe that the president is not who he says he is, despite the fact such conspiracy theories about his background have been consistently debunked.

“People I hang out with say that the trouble with him is, I don’t know, it just seems like he could do anything he wanted, and I think his agendas are totally different, and that’s how come Trump got so liked,” she says. “There’s a feeling that [Obama is] really truly Muslim even though he says he’s not.”

Terrorism in the heartland. Fears of a Muslim in the White House. These are worries in themselves. But they also are the bubbling up of a deeper angst, says Tom Stafford, a semi-retired reporter and columnist for the local Springfield News-Sun.

“The world has changed in all these immense ways. And the loss created in people’s lives, I kept waiting for it to find some expression,” he says. “I think that’s what’s happened with Donald Trump. All those issues unaddressed are going to coalesce somehow and in some way.”

Karen Duncan, a member of the city commission, says she sees the shifting changes sometimes emerge from the shadows. America’s opioid and heroin epidemic has hit the area hard; the area’s available jobs – particularly for truckers, welders, and machine operators – often result in many failed drug tests.

Employers have taken to diplomatically calling it a lack of “soft skills.”

The growth of the working poor has been marked. Many work for minimum wage at a local call center, for example, but still qualify for government benefits.

At a tech park on the edge of town, much of the land is leased to area farmers who grow corn.

“When we’re trying to attract jobs that pay very well, one of the key issues is workforce issues,” says Mayor Warren Copeland. “We’re not competitive with some other areas. This is the Midwestern disease. We’re too typical of these problems, so every other city is looking at the same problems and trying to do the same things.”

Meanwhile, the vestiges of Springfield’s historic upper middle class are growing fainter. Springfield still has a symphony, but its performances are half full. The Turner Foundation, a historic preservation charity founded by a well-known businessman and philanthropist, is something of a vestige of another time, reflecting a past when the city still had a strong corporate presence. The city of 59,700 now has fewer people than it did in 1920.

“This is a town where people show up for car shows, not for operas,” says Mr. Stafford.

The middle is being hollowed out, says Ms. Duncan. “What we wind up left with are the people who don’t have the opportunity to go someplace else.”

• • •

Mr. Rose is all about rebuilding that middle. And he is convinced that, of all the struggling Rust Belt cities with dreams of reinventing themselves, Springfield is ideally placed to do it.

As the historian at the Turner Foundation, he looks at Springfield and sees numerous gems, like the Frank Lloyd Wright house. Others just need to be polished, like the elegant, Victorian-era housing stock. And downtown sports two new white tablecloth restaurants, the coffee shop at the grand entrance of the old city market, and a near-universally attended summer arts festival.

“We have this great architecture, this great history,” he says. “My group, the people who are involved in stuff, are very hopeful.”

And Rose has allies.

Kevin Loftis, who used to work with his father in his real-estate development, has raised about $3 million locally to open a brewery in the former site of a metallic casket manufacturer.

“It’s like getting a train going,” Mr. Loftis says of Springfield. “It was decaying for years. We have momentum, and we’re keeping it going.”

Carl Carroll has bought a small, rundown bar across the street from the Crowell plant, convinced that it could become the center of Springfield’s renaissance. He doesn’t care about the bar – he’s interested in what’s going to happen with the old factory and wants to be in a good position when things take off.

He pulls out a postcard-sized picture of the old Crowell site and points to where things used to be with his pinky. “I think it will happen,” he says of the redevelopment. “I know it will happen.”

Rose agrees that the trajectory of Springfield is upward.

“Some things aren’t moving in the right direction … but things are getting better in Springfield, even though I know that’s not true for everyone.”

• • •

For Terry Davis, that future, or any future at all, is hard to see. It already seems gone.

A career in construction has left scars; both his knees have been replaced and there’s a bar in his forearm. As he shuffles by the cavernous Crowell plant, a third of which has already been razed, he shrugs when asked whether anything can be done with the site.

Then he cuts off the conversation. He doesn’t want to discuss the election or his future. He’s on his way to buy cigarettes, and he’s just looking for 75 cents.

[Editor's note: The spelling of Wittenberg University has been corrected.]