Why swing voters are vanishing from US politics

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

Here’s a prediction about the 2016 presidential election that’s almost certain to come true: Generally speaking, swing voters won’t. Swing, that is. Float. Change their preference. Vote for the Republican if they voted for President Obama in 2012. Vote for the Democrat if they pulled the lever for Mitt Romney last time out.

That’s because the United States is becoming a country where no one changes his or her mind about presidential politics. Voters are increasingly divided into reliably partisan camps. Those swing voters pundits love to talk about? They’re mythical creatures, unicorns, nothing but a flash of white in the forest at dusk. New research shows they’re now about 5 percent of the US electorate – the lowest percentage ever recorded.

Why such a static situation? It’s not because most Americans are in love with their choices. Fear and anger are likely causes of much of this sorting. Many voters aren’t so much trying to elect their candidates as block the ones from the other party, whom they see as a danger to the republic. Negative partisanship has become one of the strongest forces in this particle physics theory of US politics.

And that may be just fine with the two big parties that govern the nation. There’s evidence that they devote more attention to rallying committed supporters than reaching out to the uncommitted in presidential campaigns. They’ve been moving in that direction since 2000, when the virtual dead heat between George W. Bush and Al Gore showed them – and the rest of the nation – how closely balanced Republicans and Democrats are.

“Campaigns are changing their strategies to focus on the people who are at the ideological extremes rather than centrist voters,” says Costas Panagopoulos, a political scientist at Fordham University in New York who’s researching the subject. “My sense is that’s operating in primaries as well as general elections.”

Indeed, the decline of swing voting may help explain the partisan dynamics of this unusual presidential primary season, in which the ideological separation between the parties seems particularly wide.

Consider the GOP: Since the days of Richard Nixon, the maxim of the party’s establishment has been that candidates need to run right in the primary, then pivot back toward the center in the general election. But on immigration, many of the Republican hopefuls have moved so far to the right – No amnesty! Ship immigrants here illegally home! – that they might have a difficult time reversing course if they win the nomination.

There’s been similar rightward movement by some GOP candidates on abortion and other provocative issues.

Meanwhile, Democrats are doing much the same thing, only pointing in the opposite direction. They’re talking about everything from free college tuition to paid family leave and higher taxes on the rich. It’s hard to imagine front-runner Hillary Clinton repeating her husband Bill’s 1996 pronouncement that “the era of big government is over.”

There are a number of reasons for the development of this partisan chasm. They include the angry mood of the electorate and the rise of particular outsider candidates (yes, we mean Donald Trump).

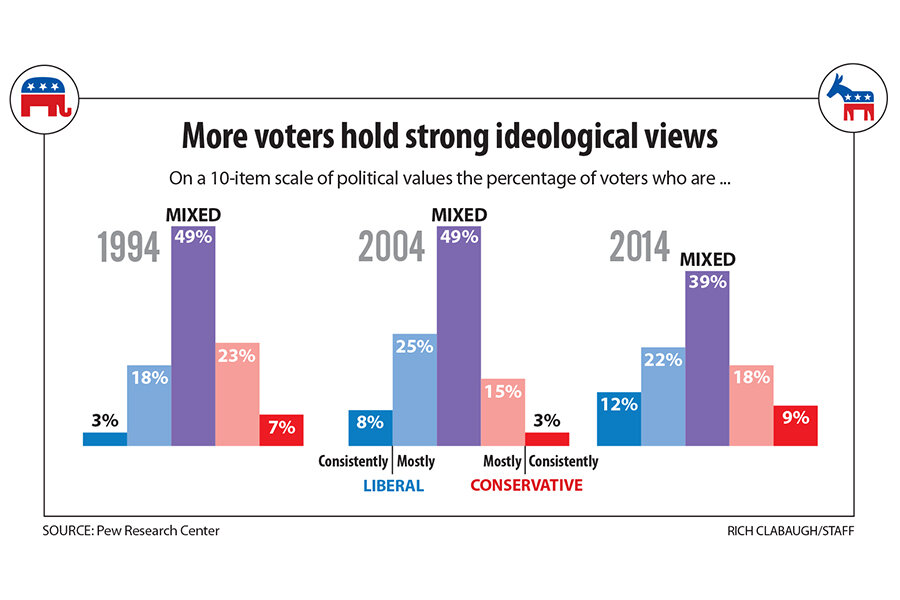

But a major cause may be that a candidate who tacks to the center will find it a much less populated place. Compared with election cycles past, there aren’t as many unaffiliated voters sitting around wondering whom to vote for. The polarization of US politics so evident in Washington has filtered down to the grass-roots level. This means parties are freer to adopt the policy choices of their most committed members, because swing voters have become less important.

“Party elites can ignore the moderating specter of floating voters because polarization has changed many of them into loyal supporters,” writes Corwin D. Smidt, a Michigan State University assistant professor of political science, in his recently published journal article “Polarization and the Decline of the American Floating Voter.”

• • •

Let’s stop a moment to make an important point: Swing, or floating, voters are not the same thing as people who declare themselves political independents.

Self-described independents are the largest category of voters in the US. A record 43 percent of Americans now say they are neither Republicans nor Democrats, but members of the unaffiliated group of “I,” according to Gallup figures.

However, if pressed, about half of these independents will say they lean toward one party or another. Another large chunk consists of low-information voters who don’t usually bother to go to the polls.

And many of those who remain have voted like partisans in recent years, whatever their personal beliefs and political motivation.

That’s the upshot of Professor Smidt’s groundbreaking study, published in October in the American Journal of Political Science. Drawing on data from the American National Election Studies (ANES) – a series of academic voter surveys dating back to 1948 – he shows that recent presidential elections exhibit the lowest levels of floating voting ever recorded.

Swing voting – defined as casting a presidential ballot for a different party than one voted for the previous election – used to be relatively common. Between 1956 and 1980 the average rate of vote switching among the entire US electorate was 12 percent – easily a big enough bloc of voters to determine the outcome of an election.

Since then that figure has dropped precipitously. In 2008 only 8.1 percent of voters reported voting for a different party than in 2004. In 2012, it hit an all-time low, with only 5.2 percent of Americans voting for a different major-party nominee, according to Smidt.

Meanwhile, the percentage of “standpatters” – people who vote for the same party over a series of consecutive elections – has risen correspondingly and is now approaching 60 percent of Americans of voting age. (Nonvoters and periodic voters account for the rest.)

The result: There may be less and less reason for presidential campaigns to trim their rough edges and appeal to swing voters in the middle. Over time this could lead to more-partisan candidates – and presidents – who in turn push voters more to the ideological edges.

“More Americans today may not identify with a party, but their behavior indicates we have never observed as many loyal supporters,” writes Smidt.

To see how this looks in real life, consider the opinions of Tyrone Quinn, an investment businessman from Chicago interviewed while on a flight to Boston. Mr. Quinn says he prefers to identify himself as an independent because voters should strive to choose whichever candidate they think is the best person.

“The hard left and the hard right, both of ’em kind of make me sick,” he says. “Career politicians make me sick, too.... Give me a good, smart, wise, and decent person.”

Quinn says that on the local level he’s voted for candidates of both parties. For instance, he’s backed Illinois Secretary of State Jesse White, a Democrat, because he feels Mr. White “is a good guy.”

But Quinn has exclusively voted for Republicans in national elections. He believes that on the Washington level the Democratic Party is in favor of uncontrolled regulation. Democrats have a “total lack of regard for spending other people’s hard-earned money,” he says.

Why have floating voters stopped floating around? Quinn’s answers hint at one major possible reason: In today’s polarized political world, almost everybody has a clear idea of what he or she thinks US political parties believe.

Sometimes these views tilt the electorate in favor of one party. Sometimes they tilt it in favor of the other. But there is little confusion or indecision about the Democrats’ or Republicans’ identities.

As recently as the early 1980s, the parties were still somewhat mixed up, ideologically speaking. The Democrats had a significant conservative Southern wing. The Republicans had liberals, primarily in the Northeast.

But that’s winnowed out now. Liberals and conservatives have separated into completely different camps. The differences between the parties have become so marked and clear that even Americans who seldom follow politics can tell them apart. So they pick a side, and stick with it.

“People are more confident in their opinions when they see polarized parties,” says Smidt in an interview. “They think, ‘Well, if the choices are so stark, it’s just not a gray area at all.’ ”

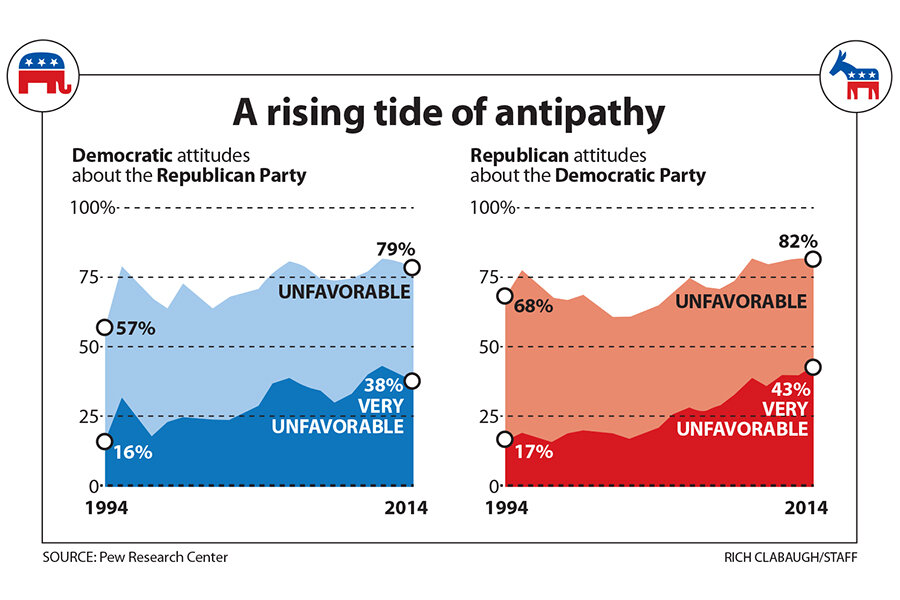

And “stark,” in this context, might mean “worrisome.” Because there’s also evidence that voters are sticking with one party not because they’re excited about it, but because they dislike, even fear, the other side.

That’s what research by Emory University political scientists Alan Abramowitz and Steven Webster indicates, in any case. They set out to directly study why partisan voting is going up at a time when fewer voters than ever label themselves Democrats or Republicans.

Their conclusion: The trend is driven by what they call “negative partisanship.” In other words, fear and antipathy. Voters aren’t so much trying to elect someone as block somebody else from winning.

Their data showed that the more US voters disliked the other party, the greater the probability they would stick with their own party’s choice.

“Along with increasing awareness of party differences, increasing negativism toward the opposing party has contributed significantly to the rise of party loyalty and straight ticket voting in recent years,” they write.

A simple thermometer scale of attitudes toward the big US parties shows the nature of this trend. Since 1980, according to ANES data, Americans’ feelings toward their own party have cooled slightly, dipping from an average of 72 degrees to 70 degrees in 2012. Their feelings about the other party? They’ve frozen, dropping from 45 degrees in 1980 to 30 degrees in 2012.

What’s behind this disparity, Mr. Abramowitz and Mr. Webster theorize, are increasing racial and religious differences between Democrats and Republicans that make it easier for voters to see their opponents as threatening, as “others.”

Nonwhites now account for 45 percent of Democratic voters on the national level, but only 11 percent of Republicans. Meanwhile, the percentage of white voters who are religiously observant (attend services at least once a week) and lean GOP has increased significantly, from 48 percent in 1980 to 72 percent in 2012.

The religious divide in particular has helped create a wide gap in party attitudes on volatile cultural issues such as abortion and gay marriage.

“The growing cultural divide among white voters and the growing racial divide among all voters have both contributed to a widening ideological divide between Democratic and Republican voters,” write Abramowitz and Webster.

This divide echoes in the words of Tara Schiraldi, a young liberal Democrat in her last year of law school at Georgetown University, interviewed in Philadelphia on a job-hunting trip.

She’s interested in working with a nonprofit that advocates for juveniles. She’s worked for the American Civil Liberties Union and the Southern Poverty Law Center. She’s concerned about what she sees as a “school-to-prison” pipeline in America for disadvantaged youth.

But the issue she keeps coming back to is women. She says she draws a line on women’s issues such as access to birth control, sex education – and, most notably, abortion.

“The way in which the Republican Party deals with women ... makes it difficult for me to feel respected by the Republican Party,” she says.

• • •

The republican and democratic hierarchies are well aware of the increasing scarcity of swing voting. For them, trying to win over voters who aren’t already committed supporters is becoming an increasingly difficult and inefficient activity, like fishing the Gulf of Maine for dwindling stocks of Atlantic cod.

So presidential campaigns, more and more, may be throwing their nets where they’re likely to catch larger numbers of votes. There’s some evidence they’ve shifted in recent years to devoting more effort to the mobilization of their party base, as opposed to the pursuit of undecided, independent, or swing voters.

Mr. Panagopoulos, who is currently a fellow at Yale University’s Center for the Study of American Politics, has examined the rates at which presidential campaigns contact various voter categories. He’s found that in recent elections that rate has risen much more sharply for committed partisans than it has for independents or adherents of the other party.

In other words, the parties are devoting increased resources to e-mailing, calling, and ringing the doorbells of their own strong supporters, instead of reaching out and trying to sway swing voters or loosely committed opponents.

“The evidence seems to suggest that the attention strong partisans receive is greater than the attention swing voters get,” says Panagopoulos.

The election of 2000 was the breaking point. That’s when the line of this trend really started to nose upward. This timing is no surprise given that Bush vs. Gore was a virtual dead heat, highlighting the need for campaigns to scramble for any possible edge. Plus, that’s when microtargeting technology and e-campaign techniques began to mature and spread through US politics, making it easier for campaigns to carry out finely tuned outreach programs.

Campaigns still try and woo new voters, of course. It’s just that they now appear convinced that there’s more bang for the donor buck in rousting old friends and making sure they vote.

“Campaigns have limited resources. They have to figure out how to allocate them as efficiently as possible,” Panagopoulos says.

It’s possible that this mobilization trend has produced a self-

reinforcing cycle. If strong partisans are pushed harder by the parties, they may vote at higher rates, electing more-partisan candidates, who push the parties further to the left or right, creating more strong partisan supporters. Rinse, repeat.

That’s a subject of Panagopoulos’s continuing research.

“The potential is that the increased focus on strong partisans has transformed the voting electorate in a more polarized way, and can be linked to growing polarization in government,” says the Fordham professor.

This imbalance in voter outreach efforts may not be a good thing for America. But political campaigns are in the business of winning, not building up the pillars of democracy. Counteracting the cycle of polarization may require efforts by the US government or nonpartisan organizations to increase voter turnout for everyone, not just those at the ideological poles.

“That’s really where the impetus is going to come from,” says Panagopoulos.

He adds, “There are all kinds of reforms that have been proposed.” These include everything from Sunday voting to easier methods of voter registration.

• • •

In the end, it’s important to remember that this state of affairs is not foreordained. American politics is not locked in a never-ending cycle in which both parties inevitably drift away from the uncommitted center. The behavior of swing voting has dwindled. The potential for swing voting has not.

The problem now is that both parties think the existing state of polarization benefits them. At some point, one or the other will likely wake up and realize that’s not true. In the past, systematic losses have had this effect.

Consider the Democratic Party of the early 1990s. After three consecutive White House defeats many Democrats decided a swivel back to more-centrist policies might be in order. That led to President Clinton, a former southern state governor backed by the middle-of-the-road Democratic Leadership Council.

“Parties are the problem and parties are the way out. People want to win,” says Smidt of Michigan State.

And possible swing voters do still exist, even as an endangered species. Take Dave Bradford, a Connecticut salesman tapping away on his laptop at the 30th Street train station in Philadelphia. Mr. Bradford voted for Ronald Reagan in 1984 because he thought the president had done well in his first term. Since then, he’s voted for Democratic presidential candidates.

“I probably lean more towards the Democrats, but as I get older, I’m more in tune with some of the Republican philosophies and stands,” Bradford says.

He thinks some of Rand Paul’s ideas are worth listening to and exploring, particularly those that deal with taxation and “taking government off our back.” He’d like to see former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg run, not so much because of Mr. Bloomberg’s political philosophy, but because of the competence Bloomberg showed as mayor, and because he, like Bradford himself, is a businessman.

“I try to vote for the person,” Bradford says.

Contributor Mary Beth McCauley in Philadelphia and staff writer Noelle Swan in Minneapolis contributed to this report.